Alas, no. The problem is more insidious and deeply ingrained: Almost every metric firms use internally to measure and reward or penalize profitability margins, compensation, and lawyer performance is billable-hour-driven. This assumption is so deeply instilled in lawyers that many have a hard time imagining it could be otherwise. But it not only could be, it needs to be:

To remain competitive in the rapidly changing market for legal services, firms must bring all of their systems and processes (including pricing, evaluation, compensation, resource allocation, and others) into alignment around consistent principles of profitability. Continued reliance on the traditional billable hour approach for all (or even some) of these purposes no longer makes economic, competitive, or practical sense.

A final thought.

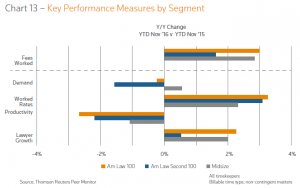

The close reader of the Report will have noted Chart 13 on page 13, which, if you ask me, contains a powerful message.

The chart displays just 11 months of 2015 vs. 11 months of 2016, but the narrative tells us what happens if you extend the comparison period to a three-year span: Every trend shown here becomes stronger and more pronounced. Those trends are simple. Here are the winners on each of the metrics shown:

- Fees worked: AmLaw 100 and Midsize

- Demand: AmLaw 100 and Midsize

- Worked Rates: AmLaw 100 and Midsize

- Productivity: AmLaw Second 100 and Midsize

- Lawyer Growth (not meaningful in terms of “winners and losers”)

The story as I read it is that you want to be an AmLaw 100 or a Midsize, but probably not an AmLaw Second 100.

That’s grossly simplistic, of course, but nevertheless or faithful authors offer an hypothesis which could explain these results, and I happen to buy it (emphasis supplied):

One possible interpretation of these results is that clients, while still directing some types of work to highend, fairly specialized, premium firms (the Am Law 50), are increasingly willing to move substantially down market to smaller firms (midsize firms) in order to achieve significant price savings. If the large firms in the middle (the Am Law Second 100 and some of the Am Law 51-100) cannot offer sufficient differentiation for their services, clients will have little incentive to change this behavior.

Yes, it’s our old friend nemesis The Hollow Middle.

The Hollow Middle dynamic is simplicity itself, and is quite widespread in the economy as a whole. Clients want the premium, high-end version of Purchase X [car, clothing, food, personal grooming] or they want to save money and economize on whatever is good enough, but the undifferentiated, not-great-not-cheap, offering languishes.

I don’t want to press an analogy past what it will bear—I studiously endeavor to leave that to others—but today’s New York Times featured an analysis of the accelerating decline of Sears, a totemic American retail brand if ever there were one, but now projected to lose more than $2 billion this year alone and “in the retailing dead pool.” The headline was Sears sells something for everyone; That’s its problem.

Amazon is not its problem: Last time I checked, Amazon had “something for everyone,” and it doesn’t seem to be hurting Amazon. No, here is Sears’ problem:

Despite the conventional wisdom, though, it is not Amazon that is primarily to blame for Sears’s plight. Sears is being squeezed by changing economies and technology. Shoppers go to Walmart for discount items or to Target for discount items with a touch of style. The high end stays at stores like Nordstrom. The middle is smaller and increasingly shops online.

(You knew I’d work Amazon in here eventually.)

Perpetually raising prices to grow revenue is like perpetually cutting costs to grow profits. You can’t play that game forever.

We seem to have pretty much concluded that we’ve played out our hand in terms of cutting costs. Private equity guys would have a different view, but firms run by lawyers are from another financial-management planet. We’ve laid off all the staff we have a heart to and we’ve de-equitized everyone we can without too blatantly shattering the Brass Ring compact. So, as the Report conclusively demonstrates, we’ve spent the last mediocre decade raising rates every year. That is beginning to provide everyone in the legal services industry who’s not a law firm—there are lots of them, and more all the time—their opportunity, as Bezos instructed us at the top.

If our new non-law-firm competitors seize their chance, it will be because we’ve rolled out the red carpet.

Each of us better figure out how we can turn our firm into Walmart, or into Nordstrom, because selling something for everyone means offering nothing compelling to anyone.

While I agree that law firms can learn quite a bit from the restructuring of the retail industry, so many of Sears’ wounds are self-inflicted that have very little to do with the market position it occupies . But Macy’s and The Gap are suffering similar setbacks, so point taken.

The dominant method for retailers to move out of the middle and to the “low cost provider” side of the spectrum is essentially an economies of scale play, primarily through pricing power/control over suppliers and keeping labor costs down. Except in the limited form of labor market arbitrage, no analogous methods currently exist for law firms serving the vast majority of SophisticatedLaw clients. Even if the motivation is there, not sure this is really an option for most AmLaw 50-200 firms as currently composed without a ruthless restructuring of most partnerships.

Skeptic: First, thanks as always for your thoughts.

Perhaps I shouldn’t have picked on Sears per se since they have been on a (largely self-inflicted, I agree) downward slide for a couple of decades, perhaps starting with the arrival of “category killers” like Home Depot and Lowe’s, to which they had no effective answer. And we can all draw distinctions where we choose–it’s something lawyers excel at!

I also agree that opportunities for labor market arbitrage in Law Land (the armies of staff and temp lawyers standing at the ready) are limited and essentially a holding action. Seriously cutting costs requires a clean-sheet-of-paper rethink of the business process model.

But perhaps, as you conclude (and as you’ll see in my forthcoming book, Tomorrowland), the greatest obstacle to fundamental change is our very own partnership model.