We cannot emphasize strongly enough how hard it is for a retailer that has spent decades in high-growth mode to turn off the store-opening machine. It has a large team in place dedicated to planning and managing the opening of stores. Employees throughout the company feel the excitement of producing double-digit growth year after year and worry that if growth slows, opportunities for advancement will dry up too. A host of consultants constantly urge senior managers not to shift strategy but rather to redouble their efforts to reignite growth. That includes making acquisitions—which all too often don’t work out. And the CEO, who has been selling a growth story to investors for years, worries about coming up with a new tune to sing.

For all these reasons, retailers often go through a long, painful period of denial before they acknowledge that growth has ended and it’s time to switch strategies. It’s likely that many of the underperforming retailers in our study are in this denial stage now. Indeed, in Walmart’s 2016 annual report, CEO Doug McMillon asserts: “We are a growth company; we just happen to be a large one”—a remarkable statement given that the fiscal year ending January 31, 2016, was the first in its history that Walmart’s sales declined.

To my mind, Mr. McMillon’s statement is beyond “remarkable:” It’s at odds with reality. But it certainly underscores the growth drug at work.

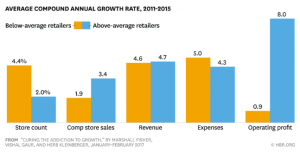

The secret separating the 17 winners from the 20 losers is not actually about revenue, but about profitability. In a nutshell, the 17 winners leveraged their existing strengths and capabilities to support their modest growth without increasing expenses proportionately. The winners are also a lot more judicious—choosy, if you will—about the revenue they do add: They grew by their net store count by just 2%/year while the losers were at 4.4%/year.

Bringing these two together, and wringing more profitability out of slower revenue growth, is the true magic. Here’s the cumulative effect:

Compared to the losers, the winners:

- opened fewer new stores (hired fewer laterals);

- grow same store sales faster (increased revenue per lawyer);

- performed not materially differently on revenue growth;

- controlled expenses more tightly; and

- blew the doors out on operating profit.

You may be thinking it’s easier said than done to grow RPL faster and control costs better, but it’s not as hard as you think. All it requires are two things most law firms have in inexcusably short supply: Talented and effective business professionals who are allowed to do what they do best (cost control, among a host of other things) and discipline and perseverance to focus on areas of expertise in your firm where laterals might actually be able to make a supra-normal contribution. Bolting on, or “renting,” revenue is the antithesis of what you need.

The savvier retailers do more on other fronts, too.

How’s this for an unorthodox technique in Law Land? The better retailers test applicants on their aptitude for and disposition towards performing the actual functions that will help them excel at their job, primarily a positive customer-service attitude and sales ability, and culling existing staff on the same basis, plus data on their historic performance.

And one last discipline the winners follow and the losers don’t: Constantly launching small pilot projects, mercilessly and relentlessly killing the mediocre ones and doubling down on the promising ones. Here, your biggest enemy is the “pet” project.

“The things you don’t do are often more important than the things you do,” Ken Hicks [CEO of Foot Locker from 2009-2014] says. Pilot projects should be conducted for each initiative, and the results should determine whether the initiative is rolled out to all stores. Foot Locker first put its scan-gun technology only in pilot stores. At the same time, it worked with Motorola to reduce the cost of the scanner, from $1,200 to $300. Only after the technology was thoroughly refined was it rolled out companywide.

McDonald’s, by contrast , seems to have forgotten the need for a disciplined process during Don Thompson’s tenure. “Management fell in love with their own ideas and lacked the discipline to kill products like Mighty Wings whose test results were questionable.”

The most important part of the book Growth Is Dead is not the the first part of the title; it’s the second, What Next? These are a few of the clues.

This is fascinating and timely.

Will you be writing anything on KWM, what it means for the other vereins and the implications generally? Been a shortage of good analysis…

The reason there are fewer discussions about law firm growth is because their is no interest in consuming those ideas. Traditional law firms are hamstrung by non-business leadership who see old solutions only. This will ultimately lead to more of what is already occurring – the gradual erosion of legal work going to traditional law firms. Alternative services providers will take more in the future. Revenue vs profitability? You can’t have a profitable organization that doesn’t exist. And an organization can’t exist without revenue. So you must have revenue. Discussions of what will produce revenue are confined in law to what doesn’t produce revenue but conventional wisdom says it does (mergers, laterals) and solutions which require compromise with non-business leadership of law firms. Growth solutions for law firms exist. There’s just isn’t any interest in them within law firms.

Would you not say that the problem of commercial law firms is less addiction to growth and more the obsession with maintaining profitability even at the risk of long-term damage to the institution? You can make a pretty good case that law firms are losing too much work because of the determination to pay their shareholder class above what the market is comfortable with (largely to in-house legal teams). You rarely if ever see a reasoned discussion of the trade-offs between organic revenue growth, investment and medium-term strategic expansion on one hand and the limitations of only pursuing 40-60%-margin service lines on the other. The focus of law firms on distributing capital to partners rather than retaining earnings only serves to heighten that short-termism.

Alex:

Thanks for this contribution; you have touched upon a wealth of issues far “beyond the scope,” as they say, of this column. But in a nutshell:

In any event, thanks again. To be continued.

Bruce