First, as much as we might like to think of ourselves as captains of our ships and deft maneuverers around the landscapes of what practices and geographies are hot, we are all subject to macroeconomic forces. As one of my favorite Managing Partners likes to remind his troops, “In the long run, we can’t do better than our clients.” A little humility, and perhaps a little portfolio diversification, might seem in order.

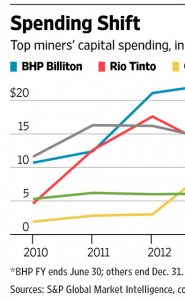

Second, if the only information you had available when you were contemplating a merger with an Australian firm looked like this:

Or, the world as we knew it in 2012 when these bets were being placed, it looked like the most obvious play in the world. All lines heading up and to the right!

So again, humility to be sure, but one other thing: How about some scenario planning? Surely had that exercise been undertaken in a serious and thoughtful way ca. 2012 one of the scenarios would have looked recognizably like what actually did unfold, we now know with benefit of hindsight.

Lest you assume this train of thought only applies to the historic one-off event of UK/Aussie law firm tieups right around the peak of the commodity boom, far from it. It applies to every decision by law firms to enter new markets–be they new metropolitan areas or new practice areas–in serious and substantial ways. It applies to single-city firms in (say) the US Midwest thinking of opening a second office and to firms “known for” XYZ thinking of expanding into UVW. Yes, we can stipulate that “the most likely forecast of the weather for tomorrow is the same as the weather today”–the linear extrapolation, in other words–but you need to think seriously and hard about other ways events might play out.

Not that you should make no bets: I will be the last voice you will ever hear advancing that counsel of cowardice and despair.

But that you might have at least thought about a Plan B when the linear extrapolation that produced Plan A dissolves in tears.

The only commodities to which I can speak from experience are metals, but what we have seen in the last 40+ years in metals is that when a rising price regime reaches 3-4 years (as you point out, the “normal” cycle), people in mining start to talk to each other in the phrase, “This time is different.” The longer the up-side, the more this is said, until it becomes conventional wisdom. And that’s just about as analytical as it really is.

Analytical tools now exist that would allow serious risk assessments to be completed, taking into account uncertainties on the supply and demand side, including political risk in its several forms, and allowing for differential risk-aversion cross firms. I would think that offering this level of expertise was something that companies like Rio, BHP, and others like Glencore with very different portfolios and histories, would expect from Big Law. If not available there, they will obtain those analyses elsewhere (e.g., Axiom etc.)

And, as you point out, it wouldn’t do the law firms a bit of harm to work though such analyses themselves with respect to their own business arrangements.

In January 2016 The Economist looked at the accuracy of the IMF’s economic forecasting and concluded that “[f]orecasts of all sorts are especially bad at predicting downturns”. Given that the IMF’s economic forecasting resources and expertise most likely to exceeds that of the average law firm I agree that it would not have been obvious to firms in 2012 that the China-driven commodities super-cycle in Australia was potentially coming to an end.

I also fully agree with the central thrust of the article that scenario planning ought to be applied to “every decision by law firms to enter new markets” but I think I’d go further and say that instead of just preparing Plan A and Plan B, how about prepping a Plan C, Plan D etc… in case things don’t pan out as expected. Moreover, it’s not enough to merely have prepared a backup plan. The firms also need to be ready to execute the plan (and execute it hard) as soon as it becomes clear that circumstances have changed and Plan A is no longer the best strategy for the business to follow.

Hoping that things work out or that ‘something will come up’ is not a business strategy, it’s wishful thinking.

IU