Nearly 20 years ago Robert Hughes published The Fatal Shore: The Epic of Australia’s Founding, still perhaps the definitive historical treatise on Australia’s founding from the continent’s discovery by the West to Britain’s decision to transport incorrigible convicts there to, ultimately, the creation of a new society. My column today is not only several orders of magnitude less epic, it’s a lot more upbeat about human nature. That said, I shall rehearse how Big Law “discovered” Australia.

Timing, they say, is everything.

And just as I noted recently that the ever-upward trajectory of globalization has plateau’d and even by some measures begun a perceptible decline, so too with mining and commodity booms.

Not to be oblique about what we’re talking about here: We’re talking primarily about Australia.

From dateline “Sydney,” The Wall Street Journal reports (emphasis supplied) that:

Global mining companies face an urgent dilemma in the grip of a prolonged commodities downturn: whether to bet heavily on new projects absent firm signs of an upturn—or wait until a recovery in prices gathers pace.

At the heart of each company’s decision is whether China is finished as an engine of torrid resources demand, or about to ramp up spending, this time on consumer goods such as air conditioners and refrigerators. If the latter, it will require commodities not at the forefront of China’s industrialization so far.

Corporate mining behemoths can basically place their bets one of two ways: As Rio Tinto has by going long and investing about $7.5-billion on expanding its existing capacity in copper and bauxite, or by going short as BHP Billiton has done in scaling down a planned expansion of its main copper mine. (BHP is also hedging a bit by experimenting with new ways to extract more usable minerals from the same raw material, but it will take nearly five years to learn whether that pans out, as they say.) The two approaches in the words of their executives:

- “We might be a little bit late to the party,” said Jacqui McGill, BHP’s executive responsible for Olympic Dam [the copper mine I mentioned].

- “The growth strategy of Rio going forward will be: Build and buy smart,” said Jean-Sébastien Jacques, who became Rio Tinto’s chief executive in July.

While their bets are clear, others admit flatfootedly that it’s tough to make a call: “It is very hard to get your timing right,” says Graham Kerr, CEO of South32 (a company assembled from BHP divestitures): “Picking when the steel market is going to be at its peak, or picking when copper will be in oversupply or deficit, the industry hasn’t been particularly good at it.”

Sure, commodities’ prices tend to move in cycles, but they weren’t ever predictable enough to really base long-term investment decisions on with any degree of confidence, and what were thought to be established cycles are harder and harder to discern of late. A standard cycle was thought to be four years boom to bust, but supercycles can last a few decades, and close observers say what we’ve been going through lately doesn’t resemble anything in the historical records going back 100 years.

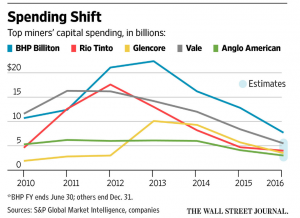

Nevertheless, it’s clear that all the Big Mining Firms have been dialing back their capital expenditures for the last five years or so:

And what was Big Law up to right around the time those CapEx lines peaked? Well, merging with Australian law firms, of course, in the expectation, among other things, that China’s appetite for raw materials would continue its insatiable trajectory. Ooops.

To be a bit more charitable here: The moral of this story, as experienced by Law Land, is two-fold.

The only commodities to which I can speak from experience are metals, but what we have seen in the last 40+ years in metals is that when a rising price regime reaches 3-4 years (as you point out, the “normal” cycle), people in mining start to talk to each other in the phrase, “This time is different.” The longer the up-side, the more this is said, until it becomes conventional wisdom. And that’s just about as analytical as it really is.

Analytical tools now exist that would allow serious risk assessments to be completed, taking into account uncertainties on the supply and demand side, including political risk in its several forms, and allowing for differential risk-aversion cross firms. I would think that offering this level of expertise was something that companies like Rio, BHP, and others like Glencore with very different portfolios and histories, would expect from Big Law. If not available there, they will obtain those analyses elsewhere (e.g., Axiom etc.)

And, as you point out, it wouldn’t do the law firms a bit of harm to work though such analyses themselves with respect to their own business arrangements.

In January 2016 The Economist looked at the accuracy of the IMF’s economic forecasting and concluded that “[f]orecasts of all sorts are especially bad at predicting downturns”. Given that the IMF’s economic forecasting resources and expertise most likely to exceeds that of the average law firm I agree that it would not have been obvious to firms in 2012 that the China-driven commodities super-cycle in Australia was potentially coming to an end.

I also fully agree with the central thrust of the article that scenario planning ought to be applied to “every decision by law firms to enter new markets” but I think I’d go further and say that instead of just preparing Plan A and Plan B, how about prepping a Plan C, Plan D etc… in case things don’t pan out as expected. Moreover, it’s not enough to merely have prepared a backup plan. The firms also need to be ready to execute the plan (and execute it hard) as soon as it becomes clear that circumstances have changed and Plan A is no longer the best strategy for the business to follow.

Hoping that things work out or that ‘something will come up’ is not a business strategy, it’s wishful thinking.

IU