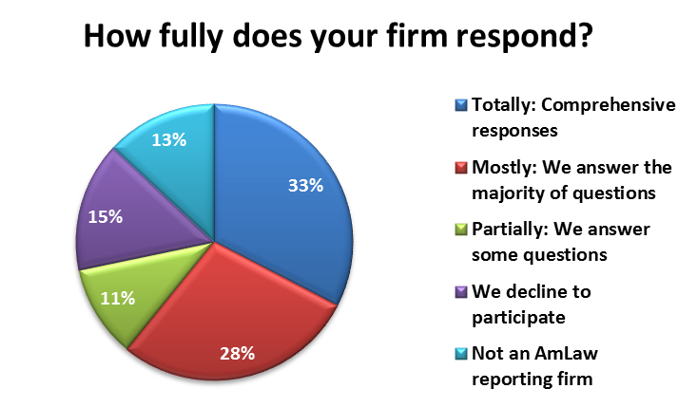

The first question asked about response rates. The graphic/pie chart follows, but to summarize, when asked “how fully does your firm respond?”

- Totally: 33%

- Mostly: 28%

- Partially: 11%

- Decline to participate: 15%

- Not an AmLaw firm: 13%

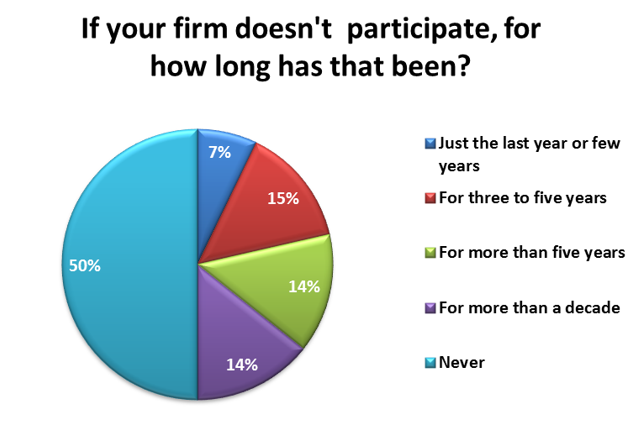

The next question followed up on firms that didn’t participate, and asked for how long that had been the case. The responses:

- Just the last year or few years: 7%

- 3-5 years: 15%

- More than 5 years: 14%

- More than a decade: 14%

- Never: 50%

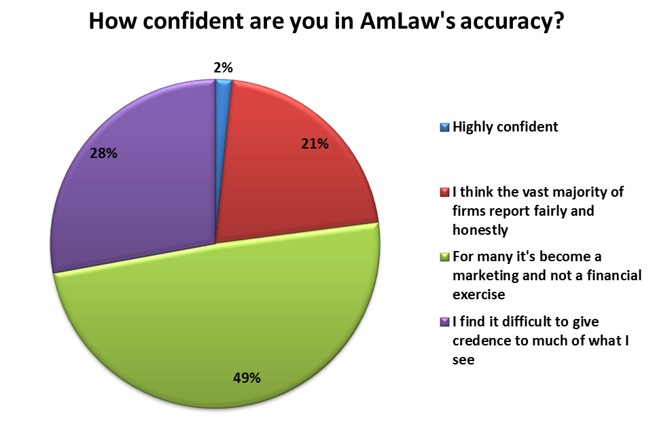

Finally, I asked respondents to characterize their confidence in the accuracy of the reported figures:

- Highly confident: 2%

- I think the vast majority of firms are fair and honest: 21%

- For many firms it’s more about marketing than finances: 49%

- I find it difficult to give credence to much of what i see: 28%

The survey invited open-ended comments, and again, while the respondents were self-selecting and those volunteering comments were presumably the most vocal by hypothesis, here are a few of their verbatim remarks:

- It’s a joke and everyone knows it.

- There’s no question there’s lots of gamesmanship going on.

- I’ve worked at 3 AmLaw firms; all 3 massaged the numbers.

- The nonequity partner tier creates hufe over-inflation of some firms’ PPP.

My hunch is that this surprises no one. This is not just sad, though it’s certainly that. It’s a sort of Gresham’s Law in action, at least if you afford Gresham’s Law (“bad money drives out good”) a commodious interpretation.

The Gresham’s Law dynamic is simply that where two forms of currency co-exist (classically, coins made of precious metal having intrinsic value), one debased through impurities or short-weighting and one of complete integrity, buyers will hoard the pure coins until all the currency remaining in circulation is debased. Importantly, this is true only if there’s a legal or practical obligation to accept both the pure and the debased at the same time and place and at face value.

Where there’s no such obligation—for example, among nations in fixing on a universally accepted global reserve currency—Gresham’s Law is inverted and good money (the US $) drives out bad (the Thai baht or the Brazilian real).

Thus with TAL’s reported PPP figures. When at least some other firms are assumed to be taking liberties to pump their numbers—it’s irrelevant which if any identifiable firm is provably in this category—scrupulous reporting can be seen as for chumps. But because there is no practical alternative (we have no choice but to accept all reported figures at face value, debased or pure), it’s understandable that suspicions arise.

This prompts a thought: Wouldn’t it be fascinating if another publication (the UK has a few covering Law Land…) were to start reporting PPP for the 200 AmLaw firms using transparent and rigorous standards. With no requirement to accept the debased currency pari passu with the pure one, would the numbers with integrity take a very high market share? Just a thought.

Let’s change the focus. Assume every PPP number reported were certified under Sarbanes Oxley standards by each AmLaw 200 firm’s Managing Partner and CFO and audited by one of the Big Four as to accuracy. What then could we say about the numbers?

First and most obviously, we’d note that they’re averages across all of each firm’s equity partner ranks (equity partners as defined by The American Lawyer, that is, namely those with at least 50% of their compensation reported on a K-1). Averages provide a handy and obvious place to start, but to really describe the distribution of partner compensation within a firm they’re nearly useless as a place to end.

Median and standard deviation would come to mind for any Statistics 101 student.

So would the simple ratio of highest to lowest, or the absolute amount of each figure.

So would identifying the figures for the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of the partner population, or the 5-10-25-50-75-90-95th percentile bars while we’re at it.

You can surely suggest your own. The point is that it would be trivial to report these numbers and would not require The American Lawyer to lift a journalistic finger. Just ask the firms.

A second and by no means mutually exclusive change would be for TAL to identify, say with an *, firms for which the reported numbers are TAL estimates not provided by the firms; this too would require less than trivial effort. I have personally suggested this to TAL more than once, to no avail.

Third is the same question I’ve asked about most other metrics in this series: What information do they contain that might inform management decision making?

With understandable justification, firms pay attention to their PPP vis-a-vis other firms in what they perceive to be their competitive set. They don’t have much choice if they want to be attuned to the risk of partner flight (the partners are paying attention, I can assure you). But if you ask the next question—”So what are you going to change if you think your peer-group PPP is too low?”—prudent and sustainable answers aren’t obvious, or at least the answers that meet one or both of these conditions require time to implement. Short term fixes will be just that.

Across firms outside your peer group, I submit that comparative PPP is nearly meaningless.

Above and beyond all this is a far larger question we don’t seem to attend to sufficiently: Since when is what we pay management a measure of the strength of an enterprise?