Along with Brexit and the apparently unsinkable Trump, another surprise has been brewing on the world stage and I hope you’ve noticed.

Globalization—measured by the most fundamental and reliable metric, crossborder trade volume—has ended its ever upward trajectory of the past half century and actually turned south. All of a sudden the economic and business commentariat, or at least those including the WSJ, the FT, the Economist, and Bloomberg, that I listen to, is remarking on this.

I thought it might be time to point this out to those of you who may have different daily Mainstream Media diets because it dovetails nicely from reports coming out of the IBA’s just-concluded annual conference held in Washington, DC this past week. As the American Lawyer reported judiciously, “A mixed message on the outlook for law firms’ global expansion met attendees at the International Bar Association’s annual conference this week.”

“Mixed” is generous to a fault if you read past the lead paragraph. The story distills a panel of (I guess—it doesn’t clarify) four Managing Partners, from Dinsmore, Freshfields, DLA, and Cuatrecasas. A few highlights:

- Dinsmore: “Why go abroad?”

- Freshfields: “Don’t.”

- Cuatrecasas [plaintively, it sounds as though]: “We were forced by our clients [to expand abroad].”

- DLA: “I can guarantee any law firm in this room can make a small fortune going abroad, if they’re prepared to lose a large one.”

The bulk of the article focuses on the challenges inherent in global expansion, including:

- A report from Freshfields that Asian partners at King & Woods Mallesons refer Australian work to firms other than its own internal Australian partners.

- If financial integration is too close (“too close” evidently meaning anything this side of the pure legal and financial separation that comes with the verein structure), “partners in the US [get] worried about the tax complexities of being a global law firm” and it’s easy to pay partners in the less lucrative jurisdictions a lot less than those in, say, London and New York. I take the latter point, but why is the formal verein a necessary condition to carrying out such an indisputably rational economic policy?

- Firms can spend tens of millions of ££ to open an office in say, Dubai (the example cited) only to face ongoing losses and the double whammy of laterals who claim such a foreign office would be essential to their doubling their book of revenue—which proceeds to never pan out.

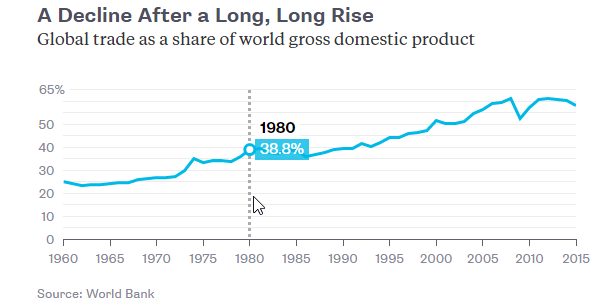

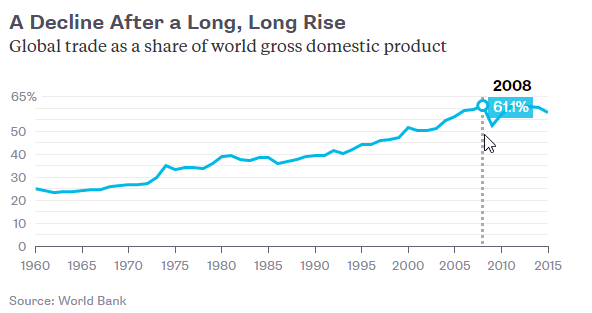

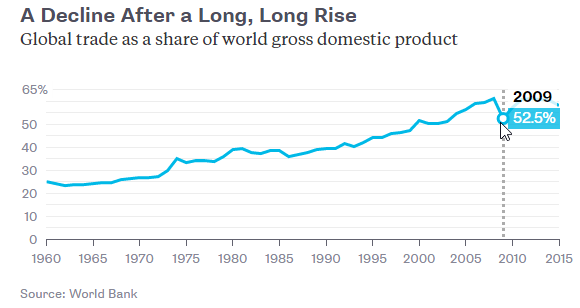

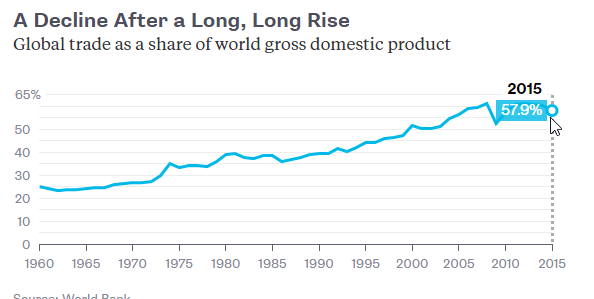

Here’s some data on the trend of global trade volume recently (World Bank data as reported by Bloomberg).

1980, when the rocket ship really began to take off.

2008, the all time peak

2009, the trough during the Great Meltdown

2015, the most recent year available:

And the Census Bureau’s trend of imports and exportsout of and into the United States (1990–2015, imports in green, exports in blue):

Other metrics give support to this. and some of the reasons why it’s happening are apparent. As Bloomberg reported earlier this month:

Here’s some good news for the hard-pressed shipping industry: Of the top 15 container lines that were in operation nine months ago, four have gone out of business or are in the process of doing so.

Here’s some not-so-good news: The global container fleet is still getting bigger.

The world’s seventh-largest container line, Korea’s Hanjin Shipping, filed for receivership last week. APL, operated by Singapore’s Neptune Orient, was gobbled up by CMA CGM earlier this year in the industry’s biggest takeover since 2005. Hapag-Lloyd is in the process of a merger with United Arab Shipping and China’s two biggest state-owned container fleets have been combined to create Cosco Container.

Unfortunately, all that dealmaking on its own does little more than change the owner’s or charterer’s name on a ship register. What the industry needs is either more trade, or fewer ships.

Remarkably, about a fifth of the global container fleet is sitting idly at anchor—up from 8% in 2007 (which is probably about the minimum level to be expected to allow loading and unloading and maintenance).

One reason for the slowdown and reversal may simply be that no tree can grow to the sky.

China is now on a mission to rebalance its economy away from hellbent-production-for-export to increasing services and domestic consumption.

Relentlessly advancing technology has steadily diminished labor cost differences between countries.

Manufacturers have learned (the hard way) that the “soft” costs associated with offshoring so much of their own supply chain are more substantial than anyone expected when the jobs were sluicing from North to South. It turns out that making products near your customers, and having design, engineering, and manufacturing under one roof, wasn’t such a terrible idea to begin with. (Before selling its household appliance unit, GE returned most of the manufacturing and all of the assembly work to its 1,000 acre “Appliance Park” facility in Louisville, KY.)

Then of course there’s the monstrous unanticipated rise of nationalist sentiment, which takes us back to where we came in.

Bottom line: If you’re a global firm, take note. If you’re not, the grass may not always be greener.