Though none of us can sanely claim to know what the future holds (I leave that to the fanatics), it’s abdicating your responsibility as a leader not to think about it. How do you go about that? In the most general terms: Creatively, deeply, and with a view to watching keenly to see what leading indicators may be trying to tell you. Somewhat more specifically, unlike telling stories about business history—where, by hypothesis, we know how it ended—telling stories about business future requires at least a modicum of suspended disbelief and trust that there’s value to be had in thinking about probabilities and likelihoods even if the hard core promise of “learning something” is beyond reach.

That’s why today I commend to you the approach taken by GE’s chairman and CEO Jeff Immelt, as described in an interview he granted McKinsey a few months ago.

Immelt’s theme, and GE’s theme for its future, is “digitizing in the industrial space,” and although that might sound about as far from Law Land as one can get, we’re all still for-profit enterprises staffed by human beings facing capable competitors, with clients who have ample choice in the market, and we’re all operating under uncertainty about the future.

The premise of “digitizing industry” is straightforward and familiar enough: The big machines GE makes—jet engines, MRI scanners, locomotives—have all become massive data-generating engines, with easily 100 sensors in (for example) a jet engine. According to Immelt, on a single flight from New York to Chicago, a GE engine could create a terabyte of data (temperatures, fuel consumption, turbine blade wear, etc.) As Immelt put it, this means industrial companies including GE “are in the information business whether they want to be or not.”

The question any capable manager will next pose isn’t surprising in the least: Given all this data, how do I want to handle the analytics the customer expects will come with it? Outsource? Do it myself? Change my business model?

Here Immelt himself draws an analogy to recent business history, emphasizing that “15 to 20% of the S&P 500 valuation is consumer Internet stocks that didn’t exist 15 or 20 years ago, [and] the [incumbent] consumer companies got none of that.” Not retailers, not banks or consumer finance companies, not consumer packaged goods firms.

The lesson Immelt drew is simple: We don’t want that to happen to GE, so “we just want to be all in.”

So I think all these things led us to say, “Let’s build it. Let’s see if we can be good at it. We may be wrong. We don’t think so, but we may be wrong. But let’s not sit back and just say, ‘Look, that’s somebody else’s job,’ or ‘We’re not good enough to do it,’ or ‘We can’t change.’” We’re unwilling to take that as a fait accompli.

Next, the question was whether to obtain the massive data analytics capability through a big acquisition, through software partners, or through building it internally. GE’s answer was that they needed to own it thoroughly, so building was the smartest, if most challenging, way to go. They started in 2010.

As I read Immelt’s interview, that just began the learning curve for GE. Here are some of the highlights:

- They built a center in California specifically to populate with data scientists and technologists.

- They’ve hired a couple of thousand people to populate it and the rest of the firm, and it’s “going to continue to grow and multiply.”

- But the data gurus don’t and can’t live in isolation: When you inject that much new DNA into a firm, everything else has to change as well: product managers, sales people, on-site support personnel, manufacturing plant workers—everyone else.

- Perhaps most importantly, to make it all work, GE has been pursuing what they call a “culture of simplification”—fewer decision bottlenecks, fewer layers, faster and fewer processes.

With distributed information and IT tools available on all mobile platforms, the days of organization charts and annual reviews are gone—”We’ve basically unplugged anything that was annual…in the digital age, sitting down once a year to do anything is weird, it’s just bizarre.”

In ways every bit as concrete, or maybe more so, GE’s business today has radically changed since Immelt took over 15 years ago: 70% of their revenue came from the US then; 70% comes from abroad today.

That’s not just a reflection of some abstract and impersonal force majeure called “globalization;” GE under Immelt has reconceived what it means to have multiple businesses under one roof when the alignment between “breadth” and “depth” have changed.

Meaning what?

Meaning the only way for firms to be strong performers in a sector is to have deep competence there. The macro-economy has changed from a decade ago. I characterize it as Law Land having become a “mature industry,” with all the implications that entails, including the transformation from a rising tide to a battle for market share, excess supply, and unprecedented pressures on prices and margins.

Immelt describes the landscape GE operates on this way:

[M]y assessment of the world is that we’re really in this period of slow growth and volatility. There’s just not a lot of tailwind; you have to make your own tailwind, and, as a result, depth matters. In other words, if you look back on the ’90s, it wasn’t that anybody did anything wrong, but you had so much tailwind you could be broader than you were deep. What we’ve tried to do is narrow our focus as a company, to be only those things that have significant core competency.

So what does this mean in concrete terms?

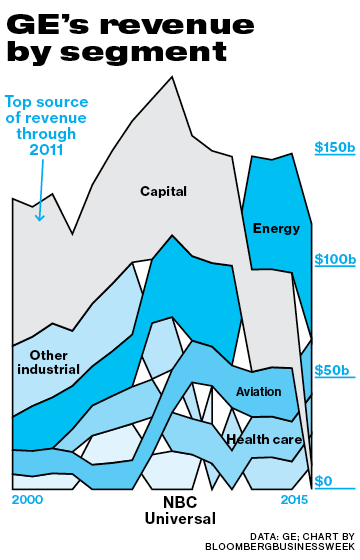

GE has become “narrower” but also “deeper”—for GE, that means depth in global infrastructure, while selling off media (NBC) and financial services. Immelt’s metaphor for what’s left at the core is the “GE Store.” GE is one company with one core capability and when you come to the GE Store as a customer, you know what you’re looking for and you expect to find it in the GE Store—and, critically, you aren’t looking for and you don’t expect to be distracted by anything that doesn’t belong in the Store.

You might jump to the conclusion that Immelt/GE thought media (for example) was a bad or unattractive business to be in. Quite the contrary:

I think NBC is a good business, was a great business. High margin. The people who ran it are great. But they never shopped at the store. They never wanted to be in the store. They never brought much to the store. Basically, we have the portfolio that fits the store.

The upshot as I take it?

Focus. Depth. Expertise. Distinction.

Faithful readers, I hope, are beginning to pick up on this as a theme here at Adam Smith, Esq. on what we believe separates leading firms from laggards.

As Verizon used to say and with thanks to Jeff Immelt’s example, “Can you hear me now?”