With the release last week of the Annual Report from Georgetown Law’s Center for the Study of the Legal Profession, the “Big Three” annual reports—Altman-Weil’s Law Firms in Transition, Citi/Hildebrandt’s Client Advisory, and Georgetown’s—are now all out and we can see what trends and developments they seem to discuss in common.

Even armchair students of the profession will have glancing familiarity with these reports, and their different approaches.

Altman-Weil’s largely incorporates and reports upon the results of their annual survey of managing partners, and thanks to their asking many of the same questions over the years, provides an extremely useful and distinctive time series tracking how responses have changed. (It’s not a strict longitudinal study since the composition of the individual respondents evolves over time, but we’re not expecting single-decimal point accuracy here.) In tonality, Altman-Weil’s approach is to emphasize “just the facts,” but reserving permission for editorial commentary (“the majority of change efforts can be characterized as limited, tactial, and reactive,” for example).

Citi’s is reliably the industry cheerleader of the group, coming down on the side of glass-half-full and partly-sunny, but their data is invaluable and their overall analysis and discussion even-handed and fair. Do not expect them to sound the alarm, however (“although low single-digit growth seems mild compared to the highs and lows of 2001–09, it’s actually similar to typical growth rates seen before that period”).

Georgetown’s, not surprisingly, tends to deliver the broadest reflections on the industry and, true to form, this year’s report is structured around the metaphor of Kodak’s legendary decline and fall at the hands of the digital photography revolution when it was a Kodak labs engineer who actually invented digital photography itself in 1975. Georgetown also features the real-world and rigorously reported data of Thomson Reuters “PeerMonitor” service. Still, “the story of the demise of Kodak is an important cautionary tale for law firms in the current market environment.”

Having studied and digested them all, what may we reasonably conclude?

For all their variations in sourcing, authorship, history, and approach, I take away two utterly consistent and indelible messages:

- (1) BigLaw’s market landscape has changed irrevocably: (a) clients are now in the driver’s seat and it is a buyers’ and not a sellers’ market; (b) demand for BigLaw in nominal dollars is barely growing and in real dollars perhaps shrinking; and (c) the proportion of “legal services” supplied by non-law-firms (including in-house departments) is growing, and at an accelerating rate. And:

- (2) The dispersion of performance among BigLaw firms—segmentation, equivalently—is growing, and at an accelerating rate.

But don’t take my word for it:

- Altman-Weil: “83% of law firm leaders say they believe competition from non-traditional service providers is a permanent change in the legal market…The biggest bite is being taken by clients themselves.”

- Citi: “As we wrote in our last Client Advisory, we are operating in a buyer’s market. […] In addition, dispersion in performance among law firms and y ear-over-year volatility in performance for individual firms has increased. These market dynamics are likely to continue. While the demand for traditional law firm services has remained relatively soft, the supply of legal service providers has increased, creating a hyper-competitive market.”

- Georgetown: “Clients who previously deferred to their outside firms on virtually all key decisions regarding the organization, staffing, scheduling, and pricing of legal matters are now, in most cases, in active control of all of those decisions… What was once a seller’s market has now clearly become a buyer’s market, and the ramifications of that change are significant. […] The increased market share of outside vendors reflects a proliferation of non-traditional providers of legal and legal-related services. Once regarded as an insignificant sliver of the overall legal market,

such non-traditional providers have now established a firm foothold in several service areas once dominated

exclusively by law firms.”

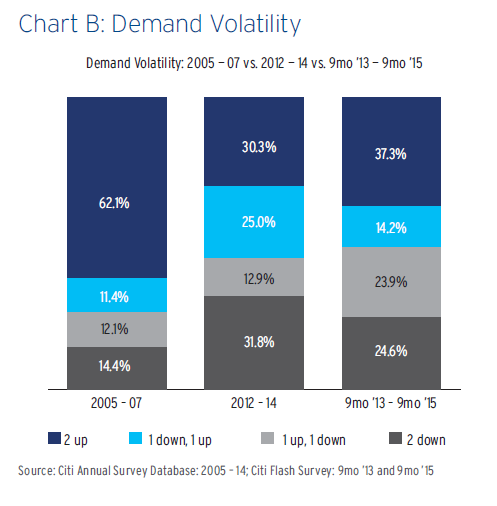

Those of you, like yours truly, who are fond of data can simply look at this chart from Citi, comparing “demand volatility” (revenue growth) in the last two immediate pre-Global Financial Crisis years with the two most recent years:

Thank you Bruce. A very thoughtful article. I’ll be signing up for more!

All the best

Sue-Ella

Interesting segue from “What’s Your Theory of Business” to this post. Maybe it was just timing, and everyone has indeed been reflecting on that New Year’s Eve post. But the lack of comment on that reminded me of some of those occasions in school when the professor would ask a question and there was dead silence, accompanied by much re-tying of shoelaces etc. Sometimes in those incidents, a good instructor will be prepared for this outcome, and will be ready with a follow-up – perhaps more obviously tied to some examples or data – that allows people to get into the flow of what the initial argument entailed.

Sophisticated clients in business disputes with other sophisticated parties have perhaps figured out that law firms are selling legal services, but what the clients want to buy is dispute resolution. Firms that can offer only scorched-earth, throw-twenty-associates-at-the-case litigation because they need to keep the crew busy are pricing themselves out of the dispute resolution market, and it’s now showing up in their numbers.