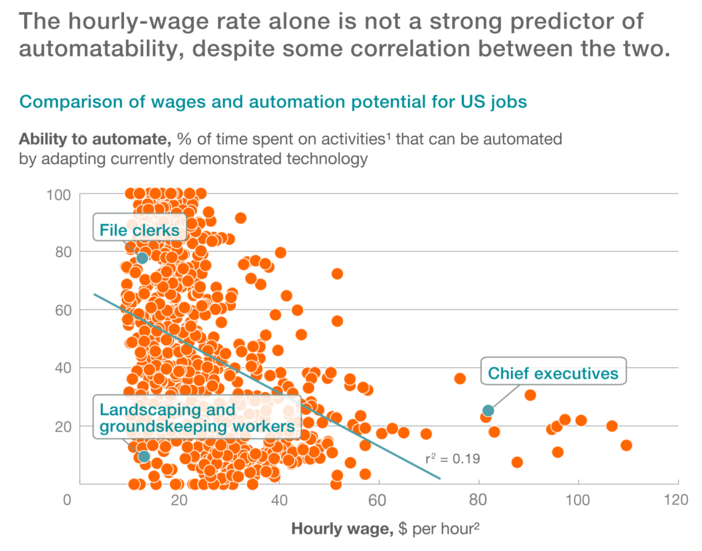

Specifically, they added into their data mix of (a) occupations; (b) work activities; and (c) capabilities, a fourth metric, namely (d) wages for each occupation. Now they can chart a comparison of wages and automation potential:

There is indeed a significant correlation (p-value <0.01) but the correlation is highly variable and wages alone fail to explain most of it (r2 = 0.19). This actually comports thoroughly with common sense. Some significant percentage of a CEO’s time (or yours) is spent digesting reports and playing air traffic controller with incoming requests, after all—neither exactly high-intensity intellectual or creative challenges—while much of what waiters, groundskeepers, nurses, and barbers do isn’t susceptible to automation on any plausible cost/benefit analysis.

So: What to make of all this?

I prefer to recast the cliche’d “The Devil is in the details” as “God is in the details.”

Trying to reach grand conclusions about will or won’t lawyers’ jobs be automated out of existence is the wrong question and leads to the feckless and circular dueling monologues of the Deniers and the Believers. Rather, you need to ask yourself, and pay intense attention to, “details” such as:

- the specific capabilities of automation to perform (highly specified) activities lawyers currently perform;

- the speed with which you and your competitors can adopt targeted technologies and redefine jobs that may have been formerly centered around now-automated activities;

- needless to say, the cost of all of this and the payback cycle on the investment, retraining, and re-engineering of your firm’s processes;

- and whether clients perceive more automation as enhancing efficiency and quality or compromising it. (I said “clients” very pointedly: This is not your call to make.)

Finally, the irrepressible optimist in me must close by revealing another finding of our McKinsey friends in their granular exploration of what workers actually do all day: What do you suppose they have to say about sensing emotion and sheer creativity, two capabilities that humans are, so I choose to believe, hard-wired for but at which machines are pathetic and may remain so for a long time into the future?

The bad news is they found:

Just 4 percent of the work activities across the US economy require creativity at a median human level of performance. Similarly, only 29 percent of work activities require a median human level of performance in sensing emotion.

I choose to interpret this not as a sad commentary on the dumbing-down of the American workplace (yes, of course it is that) but as a fat opportunity to introduce more demand for human interaction and creativity into all our daily lives. One step at a time.

How one responds to these ideas seems likely to be related to how one conceptualizes time with respect to the firm. If one sees her assignment as that of a steward for a firm with both a history and a future, then considering the situations that will be faced in one and two (or more) generations and preparing for them will cause such topics as you raise here to resonate in one way. If we are mired in the crush of daily competition, struggling with what to say to the kill-what-you-eat partners at the end of the Quarter, wondering where the working capital would come from to invest in what is effectively R&D, then the McKinsey-ASE narrative probably still sounds like science fiction.