It just happens that the other day I came across an article in October’s Harvard Business Review, “4 Ways Leaders Fritter Their Power Away,” which takes us there. What are those ways?

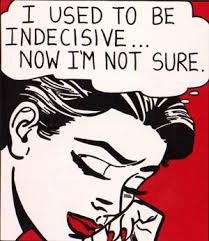

Essentially, the greatest risk to leadership isn’t abusing power, but abdicating it. Your greatest risk as a leader is not leading.

If you’re wondering how leaders fall into this trap, it’s quite seductive: “The last thing I want is to be perceived as a power-monger,” said one of the analysts’ interviewees. We can all empathize, and yet taking this too far courts disaster. It comes in these closely related forms:

- Paralysis: One victim of this syndrome earned the behind-his-back nickname “the waffle,” because he was constantly changing decisions, frequently under the influence of the “last one in” syndrome: Last person in his office persuaded him of their views. Of course, if you never want consensus to emerge or a clear direction to be adopted for the firm, this is your ticket. Everyone can claim that his or her view has your backing—because at one time or another, that has been (or will be) true.

- Over-inclusion: A perennial Law Land favorite. We want to get everyone involved, whether it’s to disperse risk or to build consensus. The problem is that when the time comes to decide, the vaunted “consensus” can disappear.“The number of people who expect to have a say in decisions is ridiculous. I spend more time building false consensus rather than increasing quality of the decision. I thought I would have more authority than I do.”

The effort to build “consensus” often resembles that spent on building a sand castle and when the decision has to be made, well, that’s just when the tide comes in.

- Accommodation: We also excel at this. Our HBR friends characterize it as “pandering to the agendas of others at the expense of a greater good.” I like this formulation because it stresses the price that must be paid, namely, the sacrifice of a “greater good.” Never forget that your job as leader is to look out for the best interests of the firm and its clients—not that of any individual partner, practice group, office, or internal faction. Part of your job will be saying, “No.” (Hint: It comes with the territory.)Does this mean individual partners should have zero degrees of freedom in terms of how they further the firm’s overall goals? Of course not; that’s not what remotely what we’re suggesting. If a goal is “greater collaboration and cross-serving,” for example, rainmakers may act on it by spreading their work more broadly; office managing partners may seek opportunities to have some work on matters done at some of the firm’s other offices; non-equity partners may delegate more down to associates; and so forth. But when the overwhelming urge to say “yes” trumps the courage it takes to say “no,” you have abdicated your role.

- Tolerating poor performance: This one has raised its head at some firms with a vengeance in the wake of the GFC. But understand that poor performance must be tolerated, and indulged in, from the top down. In terms of your role and responsibility as leader, if you leave articulation of the firm’s strategic priorities unclear, if there are no consequences for those who conduct themselves in ways antithetical to those priorities, if “mailing it in” and delivering half-hearted efforts are punished with nothing more serious than raised eyebrows and averted glances, then you have chosen who is primarily responsible for organizational drift and mediocrity: You are.

How does this square with the findings of our friends at Altman Weil?

If you believe their research, Law Land needs to get serious about addressing a disconnect with clients on the essential value of what we do. That will require change. Your partners would prefer not to (tough), and many believe clients are bluffing (they’re not). Now would be the worst time to indulge yourself—for that’s what it is, self-indulgence plain and simple—in accommodating the strident, tolerating the ineffectual (and uncoachable), or mistaking evanescent and phony consensus for high-quality decisions.

If you’re a leader, it’s time to act like one. The times, and your clients, are demanding it.

Excellent material.

There may be some worthwhile analogies in “leadership” available from looking at academic research departments. One of the standard models for academics is that “leadership” is all about doing the dismal jobs that no one really wants to do, certainly not the galacticos. In this model, being Chair is a chore, one undertaken only by late-career sorts or people who aren’t really at the forefront – it would all be to distracting. And besides, who wants a leader who actually leads, when I know perfectly well what I want to do and how to do it, including how to make my own rain if I need to do.

The story I know that offers a good example of how it can work well, even in a regime of towering egos and little or no hierarchy, is the story of Robert Sharp, Chair of the geosciences programs at Cal Tech from 1952 to 1968, a period of enormous change in the underlying science and a large-scale re-direction of the department at Cal Tech. If anyone is interested, here’s a link to the oral-history files form Cal Tech:

http://oralhistories.library.caltech.edu/90/1/OH_Sharp_1.pdf

Sharp took the department from a somewhat sleepy old-time geology department to the world’s premier program in geophysics and geochemistry, supplanting programs at Harvard and Chicago and elsewhere who could not read the writing on the wall for how the world was changing. He did it by (a) maintaining his professional expertise and teaching, (b) understanding the changing world outside just his domain, while (c) hiring the best people possible – with a few (but really only a few) lateral transfers. Sure, he helped manage the deans, provosts, presidents and trustees, but he also did it by having a strategy for what needed to be accomplished (research and teaching) and understanding the constraints (resources, time, competition) that applied. He understood his market, how his clients were changing, how to bring along junior people and work with old hands. When Harvard (where he had taken his PhD) declined to change its focus or its faculty’s ways to doing things because the new directions were not “real geology,” Sharp was ready to move and had his faculty backing the plan. And he was and remained throughout his very long career a good man, as well as a very successful one.

For any business that I know, and I should think certainly Law ( substitute tenured faculty for partners) , it is an instructive tale.

The comment from clients that firms aren’t adapting to change, and from firms that clients aren’t demanding that adaptation, could both be true. In fact, I think they both are true. It seems that the big-company clients who chime in on these points are frequently whining and complaining, while continuing to shovel money as fast as they can at the same old firms. I read anecdotes about complaints, but I don’t read anecdotes about clients who say, with specifics, I moved more work to Firm X b/c they did A, B and C.

After reading your thoughtful piece, this came to mind for me. (A tie in with a certain movie that you may know):

http://www.nbcnews.com/id/46482731/ns/business-careers/t/management-lessons-learn-star-wars/