Being unsentimental means not just gazing at the vivid picture these charts portray, but actually diong someting about it.

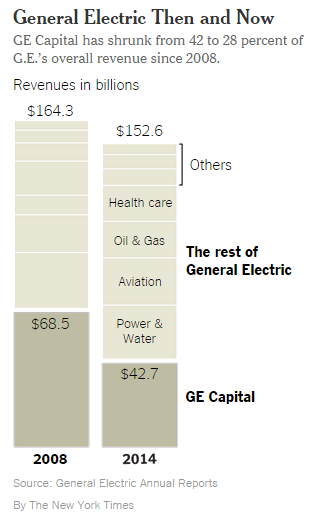

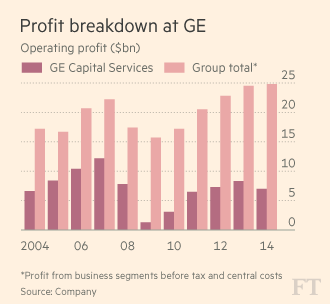

Not only was GE Capital as a percentage of GE shrinking, but of course the regulatory environment for too-big-to-fail institutions (“SIFI’s” in the unlovely coinage) was also becoming parlous. This is exactly the kind of exogenous change I was alluding to when I opened this column. The FT put it bluntly in its headline on the deal: GE Capital succumbs to the regulatory climate.

In deciding to rid GE of financial services, Immelt was doing nothing so much as taking seriously John Maynard Keynes famous observation, paraphrased by history as “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

And since you asked, the stock market loved it: GE was up 11% on the announcement, to a level not previously seen since before the Great Meltdown. What Immelt has done at a stroke is as decisive, and as simple, as transforming the company he inherited from Jack Welch: Call it back to the future if you care to, but GE, the longest surviving member of the Dow 30 industrials, is once again 90% an industrial company.

So I leave you where we came in: Have you really (really) looked at your firm lately? And what are you going to do about it?

I often think generally law firm partners think more like employees who want to secure their employment than to maximize the firm’s business. Your article is the latest example of this.

Could you imagine partners who willingly cutting off their entire practice area (self directed unemployment or scrambling for employment) if it meant that the firm’s equity could immediately improve by 11%? It would not happen under many of the current structures of law firm ownership, incentives and compensation.

You have put your finger on precisely the point I was asking readers to infer when I quoted Immelt as saying GE was “unsentimental.” Partners are (for the most part) way more “sentimental” about their co-partners than business executives are about other business executives, and certainly when it comes to one’s own practice being targeted for disosal, that takes the discussion into another planetary orbit entirely.

Question for the audience: Can you imagine a corporation converting itself to a partnership in order to receive the superior manaagement and governance benefits it would obtain?

I rest my case.

There was a well known, eminent, and successful engineering firm from the 1930s to the early 1990s who were organized as a partnership. In 1992 they converted to a publicly offered corporation. They were acquired in 1999 by a much larger firm, which in turn was acquired last year by yet another. The new combined firm has, of course, two to three orders of magnitude higher revenue and profits than did the Old Firm. And they offer services, much in demand, that did not exist when the original Names were active.

There are a handful of the original partners who are still more-or-less active. Based on *anecdotal* evidence from ones I know, they are very far from convinced that they made the right decision in 1992. Now, this may be simple nostalgia: “the older we get, the better we were.” Or perhaps economic efficiency is not the paramount value. It would make a wonderful case study to analyze in some more formal manner.

Mark L.

Mark: I speculate, but there must be studies of investment banks and/or advertising and communications agencies converting from private to public ownership, which they did in droves in the ’90’s.

I would be grateful to any readers who could point me (and you) in the direction of such studies.

And no, economic efficiency is by no means the paramount value: This is something on which I think you and I (and I hope many of my readers) agree. But how far down the list from “paramount” it can be is what I’m struggling with.

Thanks, as always.

Bruce:

I agree completely that a discussion of “economic efficiency” as a priority of the organization is needed. Indeed, it is probably a discussion that needs to be revisited over time, as the views of the founding group may not be representative of those who inhabit a “mature” organization. For lots of good, and perhaps some poor, reasons.

I would indeed be grateful if people could point us toward studies of business conversions, the more “longitudinal,” the better.

Here is a Wharton 2002 paper that addresses bank deregulation:

http://fic.wharton.upenn.edu/fic/papers/02/0239.pdf

The conclusion (about 10-15 years after the changes):

“Banking deregulation of restrictions on branching and interstate banking lifted a set of constraints that had prevented better-run banks from gaining ground over their less efficient rivals. Big changes in the banking industry followed deregulation: many acquisitions and consolidation, integration across state lines, and a decline in the market share of small banks. These changes allowed banks to offer better services to their customers at lower prices. As a result, the real economy – “Main Street” as it were – seems to have benefited. Overall economic growth accelerated following deregulation, and this faster growth seems to have been concentrated among new businesses. Sometimes we think that higher returns necessarily bring higher risk. But in the case of banking deregulation, volatility of the economy declined as

growth went up.”

So bank deregulation resulted in better service, less volatility and more growth. The counter argument for sentimental partnership is “We like historically productive (Costly but no longer have any current or projected relevance) Bob and Grace, so we’ll keep them around”? Good for Bob and Grace!

We all have observed businesses within our lives that held too long to their past success that eventually sunk them – Blockbuster is a great example. It had an opportunity to make the hard decision to cut the cord to core business (Stores everywhere, rent the latest releases!) and focus on something else (Online video streaming). The only ones sentimental of Blockbuster are former company executives, key shareholders and employees. Nearly everyone else has moved on.

JC: Thanks for the Wharton article. But I wonder if it is entirely on point as between partnership and public corporation?

If Bob and Grace are a pair of lay-abouts, dead wood from another era, then it is one thing. But of Bob-and-Grace’s practice area is producing 28% of the firm’s total revenue (the GE Capital figure for 2014), it is perhaps not so clear.

Does a partnership need to be “sentimental?” I would have thought not, and in engineering partnerships it often is not so. Perhaps the issue is whether there is someone in the partnership who is paying attention to the decline in *relative* performance, and considering whether the mis-match between GE Capital and the rets of the corporate structure in terms of markets is an important qualifier. Response maybe faster in a corporation, but – cherry picking, of course – the story of Lehman Brothers as told by Ken Auletta way back in *1985* shows that the conversion from partnership to corporation did nothing to prevent failure.

Bruce, it’s also easier for the president of a large corporation to say “the Widget Division has to go” than for the leadership of a collegial law firm (oxymoron?) to say “Bob and Grace have to go,” especially if Bob and Grace have as much voice in the decision as the leadership does.

And is the reality that Bob and Grace have a vote in the partnership model a feature or a bug?

Bruce, that depends. If the firm’s PPP is in the top quarter for its market area and practice, then it’s a feature. If the firm’s PPP is in the bottom quarter, then it’s a bug. Somewhere there is a happy medium where every partner has a voice, but not every issue goes up for a vote.