Gentle Reader:

Apologies for not having published more frequently over the past couple of weeks but business has taken us to Paris, the south of France, London, Portland, and Seattle–with 48 hours in New York inbetween the European and the Pacific Northwest trips. We met with firms ranging from the Magic and Silver Circle to US-based AmLaw 30’s, AmLaw Second Hundred, and non-AmLaw at all, and with practices ranging from globe-spanning to entirely within one state or one city.

Now that we’re back in New York for a decent interval, some thoughts on Law Land far and wide.

Believe it or not–for us it was easy to believe–the business, strategic, and financial issues firms raise bear some striking commonalities despite arising across a spectrum of firms with, in many other ways, profoundly different business models. The commonalities first, and then the differences:

- To grow or not to grow. There is an utter absence of consensus on this question. Contrast that with ca.~2007 when the Universal Solvent for breaking down the strategic conundum was to hire, acquire, merge, and combine. Understand that I’m not saying that there’s a consensus around steady-state “recruits = attrition” either. What I perceive, instead, and am grateful and relieved to do so, is that neither growing nor shrinking the firm, neither growing nor shrinking the ranks of the equity partners, is viewed any longer as the core driver of firm strategy. That driver, insted, is emerging as something along the lines of “know who you are.” This is healthy.

- Closely allied to the grow/no-grow decision is geographic office footprint; do we have the right mix of locations or is it actually more the result of history than logic? Firms across the board are–and again, this is a very healthy development–becoming much more thoughtful, purposeful, and data-driven in configuring and re-configuring their office footprint.

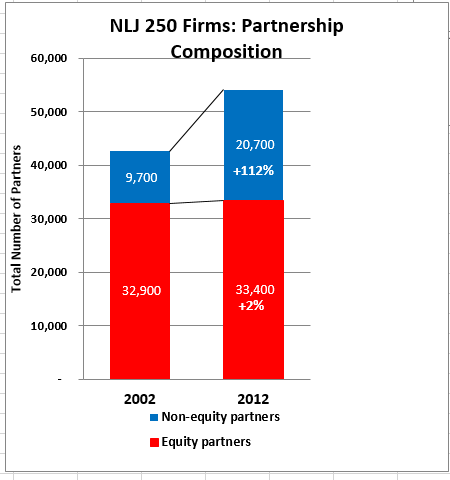

Next up I would list talent-related issues. There are two primary ones. - First, several firms wanted to discuss the place for, size of, and composition of, the non-equity or income partner tier. We’ve been waiting for this to emerge as a front-and-center issue for, well, I’d have to say years. See, for example, Checked Your Demographics Lately?, from over a year ago, which contains this perhaps counterintuitive chart:

The ranks of the non-equity have, for many firms, grown more through inattention, distraction, and passivity than through decisiveness and purpose. Firms are now beginning to pay attention.

The ranks of the non-equity have, for many firms, grown more through inattention, distraction, and passivity than through decisiveness and purpose. Firms are now beginning to pay attention. - Second, what some firms described as the “barbell” and others as the “doughnut hole” in the age distribution of their lawyers: A substantial number of relatively senior partners, a substantial number of associates and even new partners, but a relative paucity of the middle years “bench.” The heavy senior end is readily explainable through Baby Boomers’ stalwart refusal to retire, partly in response to the downturn in their retirement portfolios at the hands of the GFC, and the junior boomlet may be a pig still passing through the snake of robust pre-GFC hiring, but we have no snappy theory about the relative paudicty of talent in the middle. Hypotheses welcome. At one of our presentations, the cogent question addressing this came: “Every firm seems determined to hire this middle bench from other firms, but if nobody has them in depth, how is the market going to clear?” (I paraphrase.) My answer was that this presents a classic free-rider problem, to which there are few systemic solutions. I wish I had a more promising answer, but this is an intergenerational issue which has taken years to develop and it will take years to ameliorate.

Differences between markets largely consist of different pressures in the war for talent and pricing. To venture a gross generalization, smaller markets offer lifestyle balance in exchange for modest hourly rates, and large markets the reverse. This isn’t shocking news, but opportunities to play arbitrage between the two markets are potentially interesting, and we heard about a few savvy strategies to do just that on our travels.

Otherwise, there remain great differences in perceived growth potential across markets. Some of the most famous cities in the world are “mature” markets not just in the sense that available supply roughly matches available demand, but that no one on either side of the market sees much need for capacity to change.

Finally, across all markets there’s a growing awareness that our industry is indeed global and that trend is accelerating. Outsiders looking in was an omnipresent theme.

Of course, home at last here in little old NYC, we have seen outsiders looking in for decades. Their very mixed track record here, from outstanding success to embarrassing retreat, should perhaps come as no shock to anyone familiar with the track record of new entrants into established markets. Yet it still seems to surprise many leaders of invasions into foreign territory in Law Land.

With that, dear Reader, we shall leave you for now, except for this closing thought: The more widely we travel and the more firms’ business models we encounter, the more fascinating this industry becomes. Our wish for you is that you have the courage to create your own business model as you go forward. There are no guarantees of success nor sentences to failure (see our very own Taxonomy), but there is a palpable sense of things speeding faster and faster. Worldwide.

Bruce,

Your comments on firm composition and its strategic implications (including in the Aug-13 Demographics post your linked) took me immediately to your recent posts on leadership and then to the prior post on economics illustrated through the current Bingham information. The issues are as important in my industry as in yours.

The Bingham discussion highlights the issues of financial stability under uncertainty. This, as your prior and this post show, is an important part of the story behind the change in firm composition, in response to market demands for cost-effective service.

The “objective correlative”, comes from your leadership series, specifically the role of stewardship. The steward works in the long-term interest of her/his Principal: how shall I ensure the harvest year after year, through droughts and also floods? When must I leave the ninety-nine to recover the one? Stability under uncertainty. The answer comes not only from the imagination and training of the steward, but from a system that has traditions and tools that have been established to help the steward achieve the goals. There are experienced herdsmen for the flock, a vintner who makes good wine. And the Principal provides the tools, including the funds needed. What makes it work is loyalty (in both directions), and a commitment to the importance of being a good steward, to the idea that we work not only for ourselves, that my personal success is not the only measure of success. That we leave the household stronger than it was given to us.

If we saw our firms in a long-term perspective, then we might see how stewardship is a useful model. But without something very much like retained earnings, how can market volatility be addressed? How will we plant next-years crop, or hire and retain the people who will who will become the next generation who own and operate this land? How can we be good stewards?

Mark L.