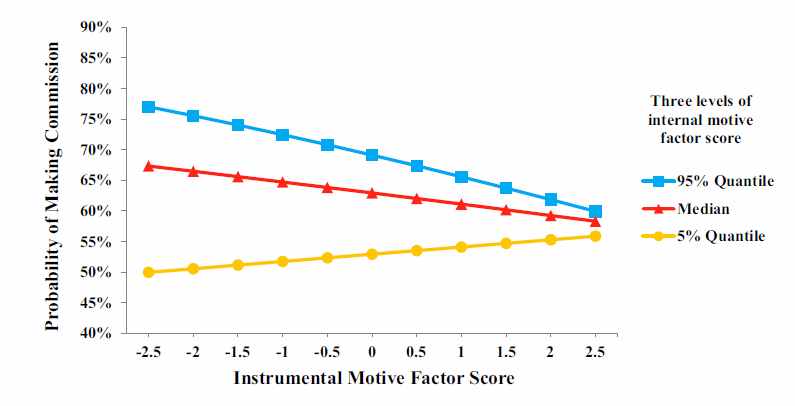

This explicitly recognizes, in a vivid way that would take a waterfall of words to achieve (and still would fail in comparative impact) the effect of explicitly mixed motives, and how the admixture of intrinsic with extrinsic motives affects outcomes.

This explicitly recognizes, in a vivid way that would take a waterfall of words to achieve (and still would fail in comparative impact) the effect of explicitly mixed motives, and how the admixture of intrinsic with extrinsic motives affects outcomes.

Let’s deconstruct what’s displayed here:

- The vertical axis, running from 40% to 90% is the probability of earning a commission for the cadet in question—think of this as the brass ring or the name of the game.

- The horizontal axis, running from -2.5 to +2.5 (ignore the units; they’re arbitrary) is the degree to which the cadet in question was motivated by extrinsic/instrumental factors: From very little to quite a bit.

- Finally, the blue, red, and yellow lines in the plot area represent cadets at the 95th%-ile, the the median, and the 5th%-ile, from top to bottom, in internal/intrinsic motivation.

In other words, no matter how strong your internal motivation—95th percentile!—if your external motivation is also strong, your odds of getting the brass ring are not statistically different from someone with virtually zero internal motivation. Looked at another way, if your intrinsic motivation is at rock bottom—5th percentile!—so long as your external/instrumental motivation is also very low, you’ve got a 50/50 chance of prevailing.

For the statisticians in the crowd, the P-score of these results is <0.0006, which is shockingly strong and almost unheard-of. Generally speaking, a P-score (roughly speaking, the odds that the outcome doesn’t actually prove anything) below 0.01 or 0.05 is considered virtual proof. Typically in social science, results like these simply don’t happen. (And it doesn’t hurt the power of these results that n = 10,239.)

Here’s how the authors summarize it:

Our results demonstrate that instrumental motives can weaken the positive effects of internal motives in real-world contexts and that this effect can persist across educational and career transitions over periods spanning up to 14 y. Instrumental motives crowded out internal motives, harming cadets’ chances of graduating from West Point and becoming commissioned Army officers. Following their entry into the Army, officers who entered West Point with stronger instrumentally based motives were less likely

to be considered for early promotion and to stay in the military ollowing their mandatory period of service, even if they also

held internally based motives.

And in an exercise in modesty, they write that “the potential scope of this undermining effect [of extrinsic motivations] on performance is significant.”

What does this mean, then, to you as a leader or a manager?

The interaction between individuals and the organizations in which they’re embedded is continuous, cumulative, and powerful, but also, I would like to believe, comprehensible. Not to be oblique about, but organizations can encourage intrinsic motivations or discourage them; encourage extrinsic motivations or discourage them.

As the leader of an organization, what can you do wrong?

- Ignore the purposes of the firm. What is this place all about? What are we building? Why should anyone who works here care? What’s the vision? Never mind: Let the place become about compensation, profits, and financial performance.

- Communicate to people through the distribution of financial incentives, bonuses, and raises, rather than through rewards and recognition for mastery and impact on colleagues and clients.

- Finally, keep a tight leash on everyone; look over their shoulders constantly and micro-manage since (it’s safe to assume) people can’t be trusted to do the right thing left to their own devices. Make sure opportunities to shape one’s daily activities are suppressed in order to maintain control.

I will leave it to the authors to sum up:

Previous research has shown that people who do the same work can view it as a job, a career, or a calling, and that people who view their work as a calling find more satisfaction and do better work than people [without that]. … Callings denote a focus on the fulfillment experienced from the work itself, often accompanied by a sense that the work contributes to others in a meaningful way. Finding ways to emphasize the internal and minimize the instrumental may lead to better and more satisfied students and soldiers.

You should be saying to yourself around about this point that you knew all this in your heart.

Nice.

Time to act on it.

In your personal life and career and at your firm.

A reader notes in a personal email that one of the more fascinating aspects of the West Point cadet dataset under study here is that it “controls,” insofar as humanly possible, for perverse “good old boy” networking prejudices and favoring, consciously or unconsciously, those who look like you.

While not perfect (women are still a relative novelty, for example), two strong characteristics govern the probability of making commissioned-officer status which are absent in Law Land: (a) Performance reviews are routinized, standardized, and regularized across all cadets for their entire Army careers; and (b) “Ivy League”/school prestige bias is eliminated, by definition, since all are West Point grads.

This makes the revealed power of intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation even more powerful by removing or minimizing the impact of other variables.

Bruce:

I think you are on a rich vein – stewardship – with the considerations on leadership. The West Point study is about as convincing a piece of social-science statistics as I have ever seen. The p-value you cite from the PNAS work is pushing the levels of quality that Jack Welch targeted (actually about 4s, but a man’s reach etc) in adopting the Motorola 6 Sigma notions.

But I have a shadow of a problem. Is it possible that the community of Army officers and the nature of their business is sufficiently different from the community of lawyers in your target Big Law that the populations don’t match? If so, what would that mean?

I have no trouble, and some experience, with the notion that being a professional military office is a sort of vocation, not just a job. And as with other archetypal vocations, the idea that there is a vocation is tied indissolubly with notions of the nature of the community, its history and traditions, and a belief that there is a common goal. “Duty, Honor, Country” is the West Point motto. How many of out firms have a motto, and if there are nay, what is their standing?

I would love to hear from others as well as yourself, perhaps as this sequence works itself out over some time in the future, as to whether and to what extent the nature of the work in Big Law ties well with the sorts of deep underpinning that are (I think) inherent in the Officer Corps and other enterprises where stewardship is well established and honored.

Mark L.