Here it is:

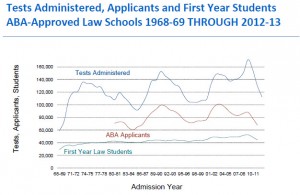

This isn’t an eye test, so let me tell you this is a time series going back to 1968 for LSAT’s administered (the top line), and 1L law students (the bottom line) with a third series (the middle line, starting in 1980) of applicants to ABA accredited law schools.

And the numbers that got my attention are those from 2009 to the end of the series, showing LSAT takers down from nearly 170,000 to barely 110,000 (down over 35%), law school applicants down from 90,000 to about 65,000 (down nearly 30%) and 1L enrollments from over 50,000 to barely above 40,000 (down 20%).

Jim was kind enough to clarify how he sees these numbers developing:

- He expects the class entering in the fall of 2014 to be in the 37,000 neighborhood (2017 grads);

- This has been stepping down about 10%/year since the Class of 2013 entered in fall 2010;

- So the total drop over the period has been on the order of 30–35%.

Note this has happened in the space of only four years.

My reaction upon seeing this was to be gratified at how dynamically the law student market had adjusted: Down at a sharper rate and with a steeper slope than ever in this time series, responding with great alacrity for such a large cohort of people to the increasingly dubious cost/benefit calculus of three years of law school with its attendant debt and depressing job prospects.

And you know that Tier 1, 2, and 3 schools—unless it’s of their own purposeful choosing—have no need to, and have not in fact, shrunk their enrollments, which means that on average the remaining schools have to be down a lot more than 30-35%, some of them a lot lot more. With high fixed costs including, most conspicuously, enough tenured faculty to support a three-year program, it’s tough to slash expenses to match large double-digit drops in revenue fast enough.

This prompted me to ask Jim, at the conclusion of his presentation, whether he expected to see some law schools close their doors. While it’s understandably awkward for someone in Jim’s position to make such a prediction, he’s far too honest to deny the possibility, while of course naming no names—much as I, wearing my Adam Smith, Esq. hat, would agree with the view that more large law firms will fail, while naming no names.

The moment of insight came as Jim elaborated on his answer (I paraphrase from memory):

What is happening is a lot more schools are experimenting—much greater emphasis on the LL.M track, of course, which has been going on for awhile, but also one-year “master of laws” programs, accelerated two-year degrees, more course sharing and tuition-revenue sharing with the rest of the university (should they be part of one), and real and concerted efforts to turn the third year into a genuine work/study mix, with students getting paid by whatever organization has hired them for the entry-level work they’re doing. This should both make them more employable upon graduation and of course help a bit with the student loan debt-load.

So no, I think schools that do a lot of these things will find new sources of income and students and may be able to escape the “one size fits all” model of legal education we’ve had so long.

What Jim left unsaid, again understandably, was the strong implication that schools that have no gold-plated pedigree to buy time in temporarily shielding them from market forces—and which don’t innovate and adapt—will go extinct.

I said this column isn’t about NALP, and it also isn’t (really) about law schools.

It’s about firms.

You are now at liberty to draw your own conclusions.

Let’s suppose that there has been a significant secular decline in the demand by Giant Corporations (call them “GCs”) for the services of large law firms, partly because the overall volume of legal work has been going down, and partly because the GCs have found other suppliers of legal services, which may be smaller law firms or non-lawyer service providers. The common result is that there is less legal work for lawyers in large law firms. My guess is that the work is down about 20%.

In that case one of three or four things should happen:

1. Most or all of the large law firms will survive, but with only about 80% of the lawyers they used to have.

2. About 20% of the large law firms will close, their lawyers will leave Biglaw, and the remaining 80% of the firms will keep about the same number of lawyers.

3. The large law firms that don’t enjoy product differentiation (e.g., firms that aren’t Skadden, Wachtell, or Cravath) will cut their prices to attract back the work to keep their lawyers busy, until they become price-competitive for GCs choosing between Big and Big Enough.

I expect the outcome to be somewhere between 1 and 2: maybe 10 of the largest 200 firms will shut down, and many of the survivors will downsize. Because of the nature of law firm management and lawyer egos, I think that this result is more likely than the big law firms accepting that, like their clients, they are subject to market forces.