I recently wrote about the depressing prospects for graduates of all but the top ten or twenty law schools (Two Law Grad Markets). And yes, these were statistical generalizations, and the experience of specific individuals with particular skills and backgrounds will always be different, pro and con. But as an industry, if you care about our supply chain for talent, many law schools are burning platforms.

There are actually some closely connected problems driving this dynamic:

- More JD’s are being turned out each year than there are (a) full-time; (b) long-term jobs (c) requiring bar passage (d) at current salary levels;

- Perhaps the primary reason for the mismatch between supply of JD’s and current demand for them (about two supplied for every one today’s market is demanding) is that clients increasingly resist paying for junior associates, which makes it uneconomic for firms to invest in traditional training;

- But/and at the same time every sentient observer is painfully aware that vast segments of the US population—consumers and businesses alike—remain underserved by lawyers.

This would prompt any economist to ask, almost instinctively, “Why isn’t there a market-clearing price where supply and demand can meet?”

Which is another way of asking, “What if there were a way to address both these problems at a single stroke?”

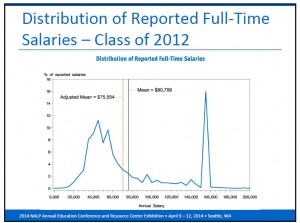

The short-term answer to why the market isn’t clearing is found in the bimodal salary distribution curve I cited in the earlier column.

Back in August 2012, NALP published a research paper outlining the history of this salary curve going back to the Class of 1991, when it bore a much closer resemblance to a normal, and to-be-expected, bell curve. Usefully, or for those of you who are gluttons for encounters with statistics that have punishing real-world consequences, NALP has also published a recap of the curve from 2006 to 2012, here.

You might well ask: Where did this curve come from?

The frankly bizarre bimodal distribution first appeared with the Class of 2000 when, in a classic case of “buying at the top,” the Silicon Valley firm Gunderson Dettmer decided to stake a claim to being among the top-tier firms out there and raised starting associate salaries from $100,000 to $125,000. (They made the move in 1999 just as the dot-com bubble was about to burst; I told you it was classic bad timing.)

Law firms being law firms, they followed like sheep and we have been living with the bimodal distribution curve ever since.

And now, you might well ask: How does it continue to endure, six years past the Great Reset?