Turnabout.

Today we have a sequel, in a yin-yang fashion, to our earlier column, “3 leading indicators of failure.”

What might the equivalent indicators be for success, or outperformance?

I’m not going to rehearse characteristics of successful firms that I consider elementary learning from Manaqement 101, or good organizational hygiene, any more than I would expect my doctor to congratulate me on my good health if I reported that I was not obese and didn’t smoke. But for the sake of thoroughness, some of the elements I consider baseline prerequisites to success and outperformance include:

- Healthy, sustainable, and honestly reported financials, with no or the bare minimum of debt;

- Strong leadership;

- A crisp, market-driven strategy; and

- Consistent and disciplined execution upon that strategy.

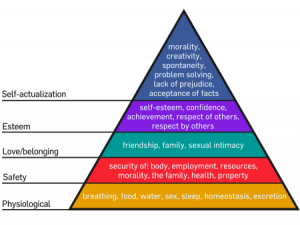

Think of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: These are the equivalent of safety and security, nutrition, shelter, and baseline good health. The interesting stuff comes closer to the top of the pyramid.

Here are my three nominees for leading indicators of out-performance.

I. A Shared and Compelling Vision

This is not the same as a carefully articulated and compelling strategy, and Lord forbid that you think it’s the same as the omnipresent and gelatinous free-roaming jellyfish concept of “culture,” which is a pox on our ability to think clearly about what our firms are really and truly designed to achieve.

The “shared and compelling vision” is widespread, ideally near-universal, agreement within the firm on what it and all who work for it stand for: An aspirational view of what we are jointly trying to build together, which is something (a) praiseworthy and laudable; (b) stronger, more resilient (“anti-fragile”) and more capable than it is today; and (c) which is plausibly within our joint reach.

This, not another 10—15%/year in compensation, is what motivates people from the executive committee to the administrative assistants to want to get up in the morning and go to work, to be cheerful, hard-working, optimistic, creative, and cooperative, and to put out the extra effort it takes to distinguish an acceptable level of performance from noteworthy and surprising levels of achievement.

Here’s an example of a vision from outside LawLand. Princeton University’s April 2000 updating of its timeless informal motto, “Princeton in the Nation’s Service and in the Service of All Nations:”

Princeton University strives to be both one of the leading research universities and the most outstanding undergraduate college in the world.

It’s elaborated upon at some length from there (these are academics speaking to academics; you must forgive them), but there’s the thrust. A child could understand it, and some of the most accomplished people in the world could also devote their careers to fulfilling it.

Your vision for the firm is the answer to the question, “What does this place stand for, and what do we aspire to make it?” It is the mutual response to the challenge of how you intend to leave the enterprise better than you found it. (You do intend to achieve that, don’t you?)

Thanks for another thoughtful, and thought-provoking article.

Your closing perspective is what gets me. Some of the paths to improvement seem well-defined; upgrading and empowering the c-suite, for example, would seem to be a relatively quick way to get a leg up on the competition. I understand that for many it won’t be “quick and painless.”

But as someone who competes mostly against BigLaw firms, the slower the better.

Bob and all:

“Quick and painless” is surely the American Disease, at least in our time. I am sure it is not part of ASE’s advice, and it seems solidly counter to most thinking of the Enlightenment that I know, so I imagine Adam Smith, himself, would have found the idea risible in any significant situation.

If lawyers were so smart at running businesses, then no Biglaw firm would ever fail.

May I quote you on that? 😉

Seriously, it is rather an accomplishment to drive a business with intrinsic gross margins of 30-50% right into the ground.

You’re welcome to quote me, though the thought (if not the exact wording) has probably crossed the mind of the management of every large business that’s seen one of its law firms close its doors.

One of the other mysteries about law firms closing is that, compared to their clients, they don’t require much capital investment. General Mills, for example, has 41,000 employees and about $23 billion of assets at balance sheet values, or about $560,000 of assets per employee. Apple Computer has 80,000 employees and $207 billion in assets, or about $2.5 million in assets per employee. By contrast, K&L Gates has about $500 million in assets (including my estimate of the firm’s A/R based on its public financial reporting) and 2,200 lawyers and legal professionals, for assets of about $230,000 per legal professional. As the reported headcount doesn’t include other support staff and administration, K&L’s assets per employee is likely around $100,000 to $125,000. It’s a lot harder to go out of business if you don’t have to sink much money into it.