Harvard economists Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff, authors of the famous 2009 book This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, are back with a study reporting their follow-up research on how major economies of the world are dealing with the aftermath of the financial meltdown.

To recap, for those who left for an extended intermission in this conversation and have become hazy on Acts I through III of this five-Act drama:

- Systemic banking crises, as a large part of the world experienced in 2007—2008, provoke decidedly different recessions than your garden-variety Econ 101 recession, where excessive consumption leads to a spike in inflation leading to central banks’ tightening the screws leading to disinvestment leading to layoffs leading to dampened consumption leading to more layoffs leading to more dampened consumption, etc. This can all be reversed by central banks’ loosening up again and pent-up demand working its wonders.

- Today nominal interest rates are extremely low and real interest rates are arguably zero or negative. This means central banks’ key weapon lacks any further ammunition.

- Reinhart & Rogoff found in their 2009 book, among other things, that:

- 43% of the 100 episodes of systemic banking crises they examined resuled in double-dip recessions;

- The median time to recover to pre-crisis levels of income was 6-1/2 years; the average was 8 years; and

- The average per capita dip in GDP was nearly 10% from peak to trough.

Their new study finds that of the 12 leading economies they’ve examined in the wake of the 2007/8 crisis, only Germany and the US have returned to their peak in real income.

The headline, such as it is for an academic paper (released at the annual convention of the American Economic Association, here in New York this week), is that all of the strenuous debate in the media about “what’s wrong” with this recovery compared to our bouncebacks from other recessions over the past 50 or 100 years is that this is not a regular recession; the only meaningful and “fair” comparison is to recoveries from other systemic financial-crisis-driven recessions.

And on that score, we’re performing reasonably well—painful as it is for all the individuals and families hit hard. In the US:

- Peak to trough drop in per capita output was “only” 5%

- It took “only” six years to get back to the pre-crisis peak

- And there’s no double-dip in sight

Granted, unemployment is still far above our post-WWII experience, and long-term unemployment, especially among the young and minorities, is excruciatingly high.

Besides the US and Germany, what about the other nine countries suffering a financial crisis meltdown? (They were France, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Ukraine and Britain.) They’re doing especially poorly, and according to Ms. Reinhart, “This crisis may in the end surpass in severity the Great Depression in a large number of countries. In fact, it may very well have one of the most protracted and painful recoveries for advanced countries in the aggregate.”

So why are we doing relatively well?

- First, US policymakers threw more fiscal and monetary stimulus at the economy early in the crisis—at least as compared with the rest of the world. (Arguably, to be fair to the EU, it was relatively paralyzed by systemic institutional constraints: In central banking land, there’s no elixir more invigorating than being able to print the currency in which your sovereign obligations are denominated.)

- Second, the US is much better at debt restructuring and workouts than most of the rest of the world. Not only is the US Treasury everybody else’s haven in a time of crisis—enabling us to borrow more cheaply than the rest of the world—but our legal system and private sector is far more tolerant, if not absolutely welcoming, of second chances and bankruptcies. For example, US homeowners who walk away from an “underwater” house lose the house, but they’re no longer liable for the mortgage debt. In Europe, the debt stays with you.

What moral can we draw for Law Land?

I think the lesson that jumps from our recent experience is that a forward, not a backward, orientation is always going to work out better. I don’t mean to make the learning sound more portentous than the facts will actually support, but one of the greatest strengths of the American civil character is that we don’t just permit but celebrate second chances. (Exhibit A: here you can lose the house and lose the debt, but elsewhere you lose the house and keep the debt.)

And for all the sanctimonious and patronizing political rhetoric spilled over TARP and all the other recovery measures, with the right denouncing governmental profligacy and the left excoriating “giant squids” of Wall Street, we finally agreed to enact a few measures that at least tried to address things, however blinkered our knowledge about what actually works in these unprecedented situations.

For Law Land, then? If your firm has a rough patch, resist the temptation to indulge in blame, naming the guilty or accusing the complicit. I know this is contrary to every lawyerly bone in your body, where a presumptive accusatory outlook on life and skeptical I-told-you-so’s are second nature, but just for once try to get past it.

Focus forward. Figure out what might work and try it. If it doesn’t, try something else. Get right back up on the horse that threw you, in other words.

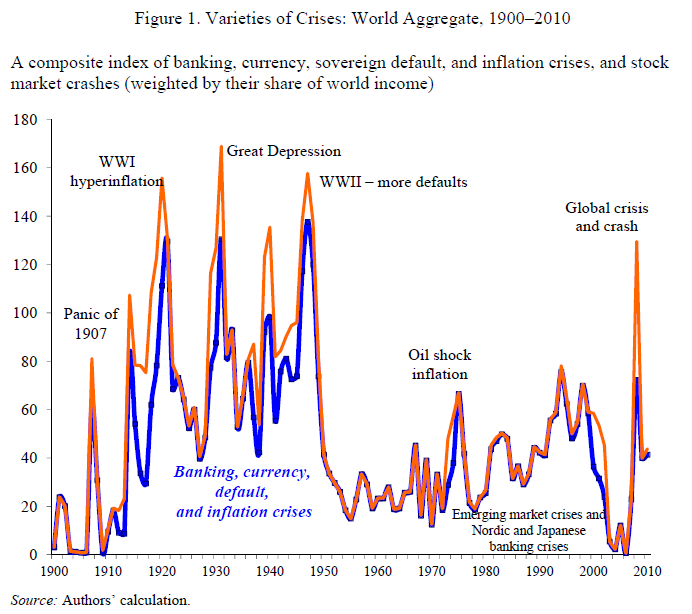

And finally, a chart from yet another Reinhart & Rogoff paper, this one from December 2013 entitled Financial and Sovereign Debt Crises: Some Lessons Learned and Those Forgotten, an IMF Working paper. If this doesn’t persuade you our recent episode was a doozy, nothing will. First the chart, then an interpretive note:

Visually, you can tell our latest economic crisis has been one of the most serious of the past century. If that’s all you need to know, stop here.

If you’re interested in how the chart was derived, this represents Reinhart & Rogoff’s own invention of a composite index across each of the world’s economies for which data is available of (a) banking, (b) currency, (c) sovereign default, (d) inflation crises, and (e) stock market crashes, each rated on a scale of 1-5, and then weighted according to each counry’s share of world income. Got that? (Read it again; it’s actually a tour de force in data reimagination.)

So if your partners are wondering why the environment seems so challenging, you don’t need to say a word.

Show them a picture.

“For example, US homeowners who walk away from an “underwater” house lose the house, but they’re no longer liable for the mortgage debt.”

Is the writer assuming a bankruptcy filing? Otherwise, isn’t that statement accurate only in states ( a minority I think) with anti-deficiency laws?

Bruce,

Why does Reinhart & Rogoff’s graph from a Dec 2013 paper stop at 2010? What do the last 3 years show?

You’d have to ask them! (I would assume that’s as far as the data from various nations could take them.)