But in 1714 Parliament upped the ante with the Longitude Act, which provided a range of prizes for what was simply called “the longitude,” scaled as follows:

- £10,000 for a method that could determine longitude within 60 nautical miles (111 km), or one degree (four minutes of time)

- £15,000 for a method that could determine longitude within 40 nautical miles (74 km), or 40′

- £20,000 for a method that could determine longitude within 30 nautical miles (56 km), or half a degree (two minutes of time), all on a voyage “…over the ocean, from Great Britain to any such Port in the West Indies as those Commisioners Choose… without losing their Longitude beyond the limits before mentioned.”

The most valuable prize was the equivalent of about $1-million today.

According to another historian of the period, no less than Isaac Newton, President of the Royal Society, testified before Parliament preparatory to the Longitude Act about the difficulty of such a timekeeping device:

“…by reason of the Motion of a Ship, the Variation of Heat and Cold, Wet and Dry, and the Difference of Gravity in Different Latitudes, such a Watch hath never been made.”

Enter John Harrison, 21 years old when the Longitude Act was passed. Harrison was born in 1693 at Foulby in Yorkshire, the eldest son of a struggling carpenter, although the family soon moved to Barrow, in Lincolnshire. John learned carpentry as a young man but by 1714 he had turned himself into a talented clock maker, constructing long-case clocks entirely from wood, which was not as odd at the time as it might strike us today. A glimpse of his later genius at discarding what everyone—including Harrison—knows to be true came when he built a “revolutionary” turret clock for the stables of the Pelham family’s Brocklesby Park: Revolutionary because it required no lubrication. 18th Century clock oils were of notoriously poor quality and the leading causes of clocks failing. But rather than trying to design a better oil, he designed a clock that didn’t need it.

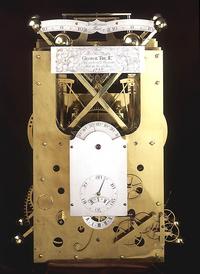

In 1728, Harrison decided to enter the Longitude prize competition. Between 1730 and 1735, he built his first entry, “H1,” which was tested on a round-trip voyage from London to Lisbon in 1736, keeping time well enough to correct a misreading of the vessel’s longitude on the return voyage. But Harrison wasn’t satisfied.

He set to work on H2 in 1737, fundamentally of the same design as H1 but larger and heavier. After three years, however, he decided his initial design was intrinsically flawed in that the bar balances didn’t always counter a ship’s motion, and they would need to be circular.

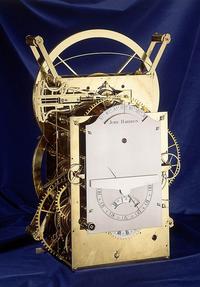

H3 took Harrison 19 years to build—1740 to 1759—but as with H2 it failed to reach the requisite degree of accuracy, despite incorporating two entirely new inventions of Harrison, a bimetallic strip to counter temperature changes, and a caged roller bearing, both of which are widely used to this very day.

In 1753 (now age 60), and having reflected on his accumulated learning from H’s 1 through 3, Harrison commenced work on H4. This time he set out in an entirely different direction, discarding everything he had done before in his life. He explained his thinking succinctly to the Board of Longitude: “having good reason to think from the performance of one already executed… that [properly designed] small machines may be render’d capable of being of great service with respect to the Longitude at Sea…”