Years ago one of my very favorite Managing Partners said to me, “We’ll know BigLaw is mature as an industry when a firm in need of a new Managing Partner does what every Fortune 500 company has done at one time or another—runs up I-95 to Fairfield, Connecticut, and steals somebody out of GE.”

For the record, we’re not there yet.

But his core insight has, with time, only gathered greater punch and urgency. (The observation I opened with took place well before the Great Reset.)

What I want to discuss in this series isn’t grabbing your next Managing Partner from the ranks of the Jack Welch/Jeff Immelt Graduate School of Intense Management Immersion, but rather treating your C-Suite with the level of respect it deserves—and recruiting and cultivating talent commensurate with the sophistication of your firm’s organizational footprint. (I use the term “C-suite” loosely, but it certainly includes any and all of your firm’s: CFO, CMO, CIO, CHRO, etc., as well as all other non-ministerial business side leaders of your firm.)

There are two sides to this coin, and they are as inextricably related as are heads and tails of that coin:

- Is there a rebuttable presumption that the folks in your C-suite should be lawyers?

- If they’re not lawyers, is their competence prima facie suspect?

I will argue that if your firm holds one or both of these views, you aren’t fundamentally serious about managing your business professionally—and I will have no sympathy for you if your mismanagement has consequences.

A prefatory remark: McKinsey (on whom we will rely in this series) estimates the managerial complexity quotient of a high-end professional services firm to be on the order of 5X that of a conventional retail, transportation, manufacturing, or construction firm. In other words, managing a sophisticated law firm with (say) $300-million in annual revenue is as challenging as managing a “something else” firm with $1.5-billion in annual revenue. We can debate—although we won’t—whether it’s 3X, 5X, or 7X, but it’s clearly >1X.

The problem is that virtually no firm I know is taking this seriously—which means acting on it. The problem is very simple: We do not treat our businesses in a business-like fashion. Shall I specify the bill of particulars?:

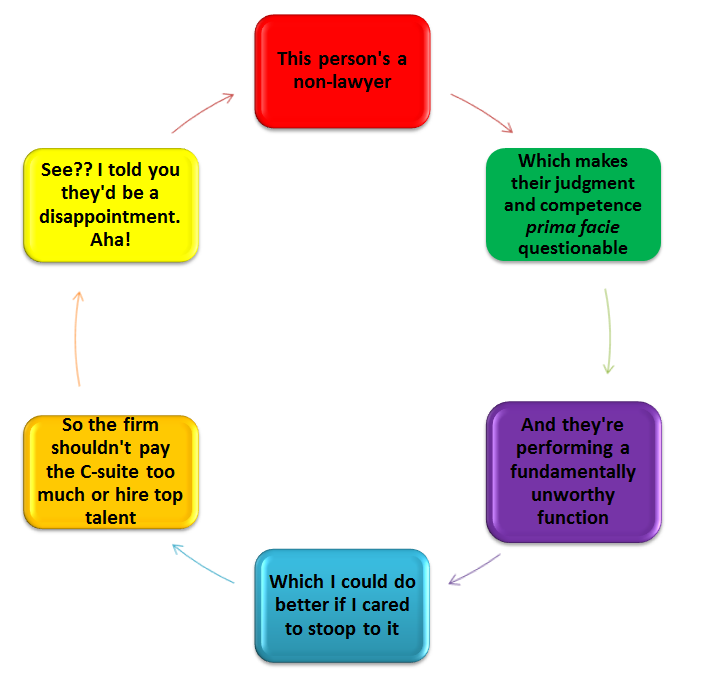

- The vast majority of lawyers, in their heart of hearts, have little or no respect for non-lawyers. A substantial minority make no bones about expressing this.

- Lawyers believe they could do anybody else’s job, probably better than that person’s doing it right now truth be told, whereas nobody else could possibly do their job.

- In far too many firms, the degree of respect and trust given to Managing Partners, the Executive Committee, and even office managing partners and practice group leaders, is inversely proportional to how much time those people spend actively managing as opposed to practicing law. In other words, the more cavalier those firm leaders seem to be about their managerial roles (we’re describing actual behavior here, and not admissions against interest except in the most egregious cases), the better the rank and file seem to like it.

- The apotheosis of this attitude—when, as the Washington DC gag has it, someone committed the gaffe of inadvertently telling the truth—was in 2007 when Mort Pierce was running Dewey Ballantine while reportedly billing 3,000 hours/year, and he delivered the immortal statement to The Wall Street Journal: “Management is not my passion.” We now know how that turned out for the firm. And, not so incidentally, do any of you doubt that any Fortune 500 CEO who said that would be frog-marched out of the building as fast as the quote hit the ether—and richly deservedly so?

- A shockingly large proportion of lawyers consciously and avowedly disdain “business” as unworthy of their attention, as evidenced by the tiresome but seemingly evergreen debate over whether BigLaw is “an industry or a profession.” (News flash: It’s both.)

- Finally, lawyers display a strikingly unattractive holier-than-Thou attitude towards even the most dedicated, experienced, and talented of professionals on the “business side” of their own firms.

Given these attitudes going in, you can diagram what’s going to happen.

If the urgency about taking our businesses deadly seriously as businesses wasn’t widespread when I had my memorable conversation with the Managing Partner who floated the GE thought experiment, it sure is today—or it had better be.

But as they say, don’t just take my word for it. I’d like to combine some insights from two seemingly unrelated McKinsey pieces that came out recently, Leaders everywhere: A conversation with Gary Hamel (May 2013), and Increasing the ‘meaning quotient’ of work (January 2013). First, Gary Hamel sets the stage nicely by explaining why The Leader of a firm—or even top leadership as a whole—simply can’t do it all themselves any more (emphasis supplied throughout quoted excerpts in this series):

I think the dilemma is that as complex as our organizations have grown, as fast as the environment is changing, there are just not enough extraordinary leaders to go around. Look at what we expect from a leader today. We expect somebody to be confident and yet humble. We expect them to be very strong in themselves but open to being influenced. We expect them to be amazingly prescient, with great foresight, but to be practical as well, to be extremely bold and also prudent.

How many people like that are out there? I haven’t met very many. Right? People who have the innovation instincts of Steve Jobs, the political skills of Lee Kuan Yew, and the emotional intelligence of Desmond Tutu? That’s a pretty small set. And yet we’ve built organizations where you almost need that caliber of person for them to run well if you locate so much of the decision-making authority in the top of the organization.

This implies that the responsibility for “leading” the organization has to be distributed down, but distributed down in a very particular way.

You will note that Hamel’s perspective comes from Corporate Land. Rather than assuming it doesn’t apply to us because we’re special, we’re lawyers (you have read this far from the beginning, right?) understand that we can learn a lot here, folks.

In most organizations, we don’t call people employees anymore—I mean, maybe somebody does—but we call them team members or associates. And we recognize that in the creative economy, most of that wealth creation is coming from people out there rubbing up against customers, innovating—certainly in a service economy, the experience economy. We talk more and more about cocreation with our customers, with our business partners.

So, already, I think we’ve understood that value is created, more and more, out there on the periphery. But we still have these organizations where too much power and authority are reserved for people at the top of the pyramid. Ultimately, yes, I think the structures, the compensation, the decision making must catch up with this new reality.

Most companies are now quite comfortable with 360-degree review, where your peers, your subordinates, and so on review your performance. In the best cases, that’s all online, and everybody can see it. But I would argue that the next important step is going to be 360-degree compensation because if you show me an organization where compensation is largely correlated with hierarchy, I can tell you that’s not going to be a very innovative or adaptable organization. People are going to spend a lot of their time managing up rather than collaborating. There will be a lot of competition that goes into promotion up that formal ladder rather than competing, really, to add value.

[…]So I think our organizations are going to evolve. We are going to catch up to this new economic reality. But it’s going to take a while because that old formal hierarchy is one of the most enduring social structures of humankind. I think making this transition—and it can seem quite daunting in a way—but I think the transition will happen step-by-step. It will happen small experiment by small experiment, where we start to say, “What can we do? What can we do in our organizations to enlarge the leadership franchise?”

Note Hamel’s critical word there: “Experiment.”

I started using the word “experiment” with clients shortly after the Great Reset. When you don’t know what the future will look like, Silicon Valley has long believed that “the best way to predict the future is to invent it.” And Hamel immediately returns to “experiments,” experiments in inventing our own futures:

Where do we experiment? How do you live in the future so other people want to follow you? How do you become one of those connectors bringing ideas and talent and resources together? That’s, again, a critical work of leadership today.

How might you actually go about this? You have to start with moving creative decisions down closer to the front lines. To do that in a responsible and effective way, information and accountability have to move down as well. As Hamel observes, you start with the “fundamental principles about empowerment, transparency, meritocracy, information, and accountability.”

This new world comes with guardrails just as today’s world does: But they’re far closer to the front lines:

So [yes, of course] there are preconditions here. This is not some romantic thing—you know, “let’s just give everybody more power” —because that’s probably chaos. But if we equip them, give them information, make them accountable to their peers, shorten the feedback cycles, then I think you can push a lot of that authority down in organizations.

I can hear you thinking already: Yes, well, splendid notion to be sure, but (a) how do we get people engaged because leadership is, after all, leadership’s job, and (b) can they be trusted?

Those will be our topics for the next installment.

Bruce,

What you describe here has elements of two common problems on other areas: 1) succession in new companies; 2) administration of university departments. The unified vision and commitment to initial intellectual framework of the founders of an enterprise feed a contention that no other set of qualifications, even well after the initial founding, is realistic. Academic departments are infamous for a belief that the Chair should leave everyone else alone, and woe be to the Chair who is thought to be intellectually second-rate or a “careerist”.

The dysfunction that comes from both examples is legendary. What is common to both, and also to your proposition, is that the people who are supposed to be members of a community at a decision-making level act is if they do not understand that the life of their community depends on the continued functioning of the economic circulatory system. That is not the only sub-system that is important, and no one thinks that it is. But cash flow, backed ultimately by profits is essential to the continued existence of the functioning entity.

the sort of innovation required to change law firms can come from the top as well. Look at the example of Peter Kalis at K&L Gates. He released his firm financials and rightfully challenged the authenticity of the AmLaw 100. He believes in organic growth – not Swiss Verein merger mania. He has orchestrated mergers..yes. In key international markets. He’s one law firm managing partner to emulate – and I believe change can and should come from the top as well as other ranks within a law firm.