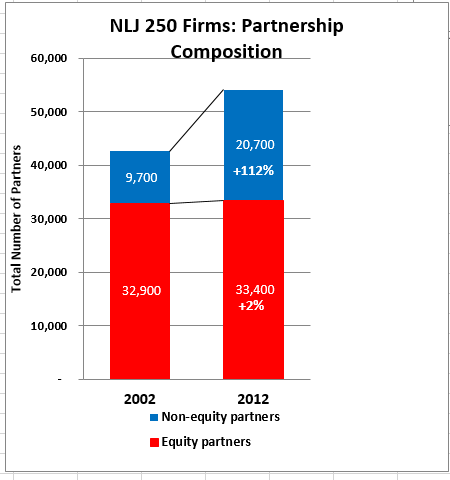

Here are the numbers:

- Equity partners grew from 32,900 in 2002 to 33,400 in 2012, or +2%

- Non-equity partners grew from 9,700 in 2002 to 20,700 in 2012, or +112%.

Visually:

No, I didn’t see that coming either: At least not to that extreme degree. When you stack this up against the total change in headcount in NLJ 250 firms, you find:

- Equity partners in 2002 were 32,900 out of 102,533 total lawyers, or 32.1%

- In 2012 they were 33,400 out of 126,293, or 26.4%—down 18% in relative share.

- Non-equity were 9,700 out of 102,533 in 2002, or 9.5%

- And by 2012 had grown to 20,700 out of 126,293, or 16.4%—up 73% in relative share.

First let’s talk about why this might be happening and then let’s talk about the ramifications.

Why?

I nominate the following suspects:

- Clients are increasingly pushing back against paying for associates, but seem more willing to pay for partners. The realization rates on the average hour of partner billing time is higher than the realization rate on the average hour of associate billing time, and clients like the “aura” of advice and attention from a partner.

- Non-equity partners are:

- cheaper than equity partners

- easier to “make”

- and easier to un-make, and even to get rid of.

- In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s many firms—about 80%—switched from single-tier (equity partners only) to two-tier (equity and non-equity). This was typically undertaken on the belief that doing so would increase leverage and hence profitability for the remaining equity partners. The story the numbers tell on that score is actually rich and complex and it’s not at all clear that higher profitability was ultimately served by this switch (consider simply that the firms with the highest year-in-year-out profitability are still single-tier), but quite a switch it was. Still, introducing the new breed into the mix—non-equities—was seen and felt, accurately, to be a marked departure from decades and decades of prior custom, so it probably took the passage of time before growing the ranks of the non-equity class substantially was even in the cards.

The result is simple: We see many firms moving from a pyramidal to more of a diamond-shaped personnel-structure model, with proportionately fewer full equity partners and young associates in the mix, and higher headcount in the middle ranks. This seems eminently rational and, indeed, seems to be responsive to clients’ expressed preferences for more experienced lawyers whose rates are still kinder and gentler than the real meat-eating go-to partners at the very top. I understand.

Now, the ramifications.

Bruce – great post and as always, you cut to the most important issues to discuss.

The numbers don’t lie, but I’m not sure that I am ready to accept all of your short and long run conclusions … you may be right – especially regarding your assessment that you shouldn’t create these kinds of classes for short-term profitability or to avoid difficult management decisions and responsibilities. But something in me is uncomfortable with regard to your last few conclusions – I can’t help but think that you’re making presumptions about who non-equity partners are and how they’ll behave based on a long-standing bias about what drives equity partners and how they’ll behave. I think it’s dangerous to define today’s non-equity partners based on those terms. I think many represent a new breed of legal professionals who are anything but equity partners’ Mini-Me’s.

The truth is that this experiment is still young and many of the results are not yet in: what it is that drives lawyers to choose different relationship status with their firms in today’s marketplace is fundamentally changing with both generational and emerging new market realities.

For instance, I’m not so sure that non-equities might not be MORE loyal to the firm or BETTER shepherds of long-term client interests than their equity colleagues going forward. Many seem far more institutionally committed to their firms than many of their equity colleagues. If we are truly moving from a law firm service model that rewards activity and revenues toward one that rewards results and profitability, then I’m not so sure that logic dictates that the equity partners in today’s firms are better or more loyal to the cause of long-term health and increased firm profitability.

More to the point, I’ve found a lot of fault lately in the behaviors and driving incentives of some equity partners in some firms lately, who are anything but “firm-loyal” or “client-interested.” Hoarding work, avoid strategic decision-making, holding hostage or nixing important investments, and constantly shopping for a more lucrative firm in which to perch are not the hallmarks of partners who are investing in the long-term health of their firms. I’ve also seen (and am honestly still learning about) the changing work ethic of many younger lawyers today – they are incredibly committed to their work, the quality/improvement of their practice, and their clients – just not to self-obsessive point that typified my generation. Many in my generation only know how to reward lots of hours, which isn’t what value-based services demand. My generation judged lawyers’ merit by whether they billed more hours, were willing to skip weekends and cancel vacations, and agreed to put off having families (or investing in other interests in their lives) so that they could be seen as loyal team players. Is that really how we should define either loyalty or merit in a firm today? Does that kind of thinking or practice really drive success, or increasing dysfunction?

Of course, in discussing this issue, we’re both making generalizations in order to advance our arguments and tweak the discussion. Just as you believe that many non-equity partners provide great value, I know many equity partners who are the most invested, strategic and firm-aligned leaders on earth.

My comment is simply to note that your judgment of how non-equities will behave over the coming years is based on a presumption that lawyers in both equity and non-equity classes are still the same creatures that most lawyers were a generation ago, before this experiment really got underway; it’s based on a presumption that they work in firms that will succeed if they continue to drive traditional thinking about how it is that lawyers should contribute their talents to assure success for the firm. I think times are changing the definition of successful business models and that there are new breeds of lawyers out there in both classes who will behave much differently, and are driven by different interests, than their peers and firms in the past. And that accordingly, the jury’s still out on whether the non-equities of today will or won’t end up making incredibly valued and important contributions to the long term health of their firms. We agree that firms must deliberately choose to create non-equity tracks for the right reasons and with insight and forethought. I don’t believe that it is a given that those who made that decision, however, will find that their long term interests aren’t well-served by their choice.

Thanks, Susan:

Not just for your generous words (of course), but for realizing the fundamental point that this is not about equity vs. non-equity partners (or either of them “vs.” associates, for that matter).

It’s about the long run “organizational health” of firms, and their ability to adapt and thrive on a vastly more challenging competitive landscape.

The whole point of this column is to get firms thinking – if they’re not already – about what type of professional workforce they want to have for the long run. And whether they think about it or not (most, I submit, have not really thought about it in a disciplined way across their professional populations), they will get the workforce they deserve.

Bruce

One issue with your analysis is that it seems to be missing some fundamental information. At my firm, at least, non-equity partnership is looked at as a “first step.” Unless you built up a large book of business as an associate (which rarely happens these days, since few clients want to hire an associate as their main attorney with the firm), if the firm likes you and wants to keep you, you get made a non-equity partner. You then start using your new title and the access it provides to build your book. When you have a strong book of business, you are then put up for consideration for equity partnership. Obviously some people will stay at non-equity and some will even start as an equity partner, but it’s not the plan for the attorneys or even the norm. Your analysis seems to overlook this, and possibly misunderstands the way partnership is approached in these new times.

Stacy:

Many thanks for taking the time to contribute; I appreciate your observations.

At the risk of abusing Tolstoy, the reality of law firm land is not far from his observation about happy and unhappy families: “All single-tier partnerships are alike; all two-tier partnerships are two-tier in their own way.”

Believe me, I’ve seen many different ways firms define, manage, populate, de-populate, and in general control the non-equity tier. They can be, for example:

The thrust of this column was not remotely to debate the merits, demerits, strengths, and weaknesses of the concept, existentially if you will, of a non-equity tier. The thrust was to point out that our firms’ demographics have changed rather dramatically in ways that I believe too few people appreciate.

Thanks again,

Bruce

Bruce,

I enjoyed this post–but was also troubled by something critical I felt was missing. We all focus on what means the most to us—and in addition to my many friends and colleagues still stranded in the senior associate and income partner phantom zone, I have devoted the four years since leaving my firm (after 25 yrs) to pressing for improved business, business generation and other practical skills training for associates and young partners. So while I appreciated your digging into a topic most lawyers and commentators are uncomfortable discussing, I think you missed an opportunity to hold firms accountable for the ways in which they may have failed their associates and young partners, setting them up to be set adrift as client demand for high priced legal services dipped.

Ed Reeser said it perfectly in a post last week– law firms need to get back into the “people business”. And I don’t think they can really “manage for the long term”, as you put it in this post, until they do.

What most concerned me in your post was the apparent assumption that client-centric skills are instinctive. You use the word “instinct” when emphasizing the urgency of the situation for those firms less hardy than the top tier. But–in my own experience, I am certain that many income partners could have been “A-players” had their firms offered put in the time to build the A team.

So–although you directly address the fact that law firms are somehow missing the point–that it’s all about the “people”….the talent (talent that has –like the average over-abundant lateral — disappointed), I wish you had also taken them to task for the myopic decision-making that resulted in fine lawyers being under-skilled in business generation and client development.

There are a few law firms out there who have chosen to invest hard dollars AND substantial, otherwise billable, partner hours in the development of their future partners. Really the hours –and even (call me crazy) some credit sharing and sponsorship–would be vastly more important than the dollars…but–of course, time is money..

Our new lawyers arrive on the job with little business and finance knowledge, minimal practical legal skills, and a weak professional network—-well behind their contemporaries in other corporate settings. Most of their firms still manage people and profits off the billable hours comp and pricing model.

We don’t disagree that management has lacked vision…I’d just like to dig back to some original sin, and try to fix it. This generation of lawyers has got to be broadly and deeply trained to survive, and to succeed us.

Anyway, thanks for providing a worthy topic for my long neglected blog. 🙂