Finally, “Placement Success” (USNWR language) accounts for the final 20%. The problem is that this metric is as arbitrary as they come, being a dart-board toss combination of employment at graduation and nine months (270 days) later. This is one of those consummately meaningless metrics, which nevertheless achieves the daunting hat trick of:

- Saying nothing about what any actual, sentient, human being would define as employment prospects or care about;

- Being consummately manipulable (schools have been known to hire their own grads for part-time jobs at the magic nine month mark—pure coincidence, I hasten to assure you); while

- Still sounding objective, unbiased, and above the fray.

So what goes into the ATL rankings?

First, a bit more about their philosophy, starting with why they only list 50 schools, not the entire steroidally expanding universe now approaching 200 with the ABA cheering loudly on he sidelines. Forgive the extensive quote, but this is such a refreshingly revolutionary, clear-eyed, and needed approach that all of us who’ve been imprisoned in the USNWR cave for so many years need the oxygen it provides:

Why would we limit the list to only 50 schools? Well, there are only a certain number of schools whose graduates are realistically in the running for the best jobs and clerkships. Only a certain number of schools are even arguably “national” schools. Though there is bound to be something arbitrary about any designated cutoff, we had to make a judgment call. In any event, the fact that one law school is #98 and another is #113—in any rankings system—is not a useful piece of consumer information.

The basic premise underlying the ATL approach to ranking schools: the economics of the legal job market are so out of balance that it is proper to consider some legal jobs as more equal than others. In other words, a position as an associate with a large firm is a “better” employment outcome than becoming a temp doc reviewer or even an associate with a small local firm. That might seem crassly elitist, but then again only the Biglaw associate has a plausible prospect of paying off his student loans.

In addition to placing a higher premium on “quality” (i.e., lucrative) job outcomes, we also acknowledge that “prestige” plays an out-sized role in the legal profession. We can all agree that Supreme Court clerkships and federal judgeships are among the most “prestigious” gigs to be had. Our methodology rewards schools for producing both.

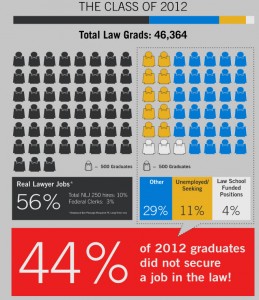

Now more than ever, potential law students should prioritize their future job prospects over all other factors in deciding whether to attend law school. So the relative quality of law schools is best viewed through the prism of how they deliver on the promise of gainful legal employment. The bottom line is that we have a terrible legal job market. Of the 60,000 legal sector jobs lost in 2008-9, only 10,000 have come back. So the industry is down 50,000 jobs and there is no reason to believe they will ever reappear. If you ignore school-funded positions (5% of the total number of jobs), this market is worse than its previous low point of 1993-4. The time has come for a law school ranking that relies on nothing but employment outcomes.

So what matters, and what doesn’t? What does not matter are “inputs:” LSAT scores, GPA, student scholarships, and more. What does matter are results: Full-time legal jobs requiring JD’s, school costs, and alumni satisfaction. At a more conceptual level, here’s why it’s important that USNWR is looking at inputs and ATL is looking at outputs.

Judging quality by what goes into a good or service rather than how it actually performs in practice is an error of the first order. This is not an abstract notion: Would you rather drive over a bridge whose engineers had designed it to support XXX thousand tons (XXX being appropriately defined, of course) or who had relied on an expensive steel alloy without calculating what weight it could actually support? Yet it’s such a common fallacy as to defy belief: Closer to home, the ABA, in accrediting law schools, values such antique things as the amount spent on the library and (conversely) won’t give credit for adjunct professors. And the upshot is they invite the Law of Unintended Consequences to kick in brutally.

Many is the conversation I’ve had lately about the seemingly glacial, but accelerating, migration of our industry from prestige-driven to outcomes-driven, and this is one milestone along that salutary path. (The enormous issue of “prestige” vs “outcomes” is worthy of one or more columns of its own, but lest anyone take immediate umbrage at my questioning one of the profession’s century-old pillars, suffice to say for now that prestige should follow from consistently superior outcomes and not be floating without visible means of support in mid-air, thanks to some ancient and indecipherable runic decree.)

So I fundamentally agree with the methodology. A second welcome element is that that graphic presentation is both vivid and informative:

And finally, as one has come to expect from Above the Law, the writing is fresh and conversational. For example, answering the self-posed question, why does employment score merit a 30% weighting, they write:

I agree that the ATL ranking is a good effort. And I agree that Elie’s follow up post, discussing some of the criticisms, was an unusual display of forthrightness on the part of somebody making rankings. My criticism is that a number of the inputs are also quite easily subject to gaming. For example, the NLJ250 data isn’t an ideal proxy for employability (at least not at the top). That is, the NLJ250 ranking evaluates a placement at Cravath, Wachtell, or other similarly situated firms as equivalent to a placement at Adams and Reese. Not to suggest that Adams and Reese isn’t a great firm, but I think that few would suggest it’s in the same league as the others. Unfortunately, this is a feature that actually does have an effect at the top. At that level, I think that the relevant question is less about access to jobs as much as willingness to take certain jobs. The biggest outlier is, of course, Yale (comparatively few do biglaw), but the data underlying the NLJ250 ranking suggest that Penn students are actually willing to take firms a step down in prestige from, say, those that NYU students are willing to go to. So that’s a concern.

Batch rankings are the key. If you look, the scores tend to cluster anyways.

Also, you are completely on point with abandoning scholarships as a metric for ranking schools, but only insofar as it comes to choosing which school to attend. At that point, of course, you’ll already know which school gave a preferrable funding package. But it might influence the decision to apply to schools, given the cost of application (why apply to a school that I know I will not be able to afford?).

The biggest issue is the assumption that all NJ250 firms are equal, and that NJ250 firms + SCOTUS or federal judges are the only desirable rankings category. I agree with ATL that they need to draw the line somewhere, and that line should definitely be above “JD preferred,” but what about prestigious (according to ATL) programs like DOJ Honors, or generally desirable other federal honors attorney programs? No one goes to the DOJ because they didn’t get their first choice job at a big firm, unlike many JD-preferred positions.

What I would like to see is a report looking at the influence US News actually has in applications and enrollment. Are prospective law students making their choices based on the US News Rankings? I haven’t seen any studies on this topic.

Further graduate education in general is facing a crisis, not just law school. The legal community needs to look at the larger picture and outside their insular profession and see that many have faced or are facing similar problems. Collaboration to find a solution or reviewing ones that worked should be part of the solution method. Not just get a room or committee full of lawyers and law professors/school administrators together to come up with a solution. Having one economist is a mistake when a major portion of the crisis is about pricing. A committee of economists would be much better.