As we come to the final installment of the Growth is Dead series, I hope the challenge I’ve laid out for us is clear.

- Excess capacity

- Stagnant demand

- Cut-throat or “suicidal” discounting

- Unprecedented pressure on prices, from all directions, including who clients will pay for, and rates and realization

- Exhaustion of cost-cutting as a tactic to keep profit margins intact

Among other things, I’ve suggested the new landscape will require:

- Law firms to restructure their “demographics” in profound ways, from pyramids to cylinders

- And far savvier and nimble readiness to draw upon “the cloud” of virtually available talent, be it alumni networks, your own onshoring operations, or even third parties

- (Think of all of this as just-in-time supply)

- Astute, targeted, knowing focus on clients’ businesses so that they come to see you as partners in solving their problems and not the “outside counsel vendor”

- Willingness to invest for the long run and not feel compelled to strip-mine the balance sheet of cash within weeks of the conclusion of each fiscal year

Note that last point.

My greatest fear for the industry at this juncture is that short-term imperatives will override sound judgment and prudence, and that a few firms may be tempted not only to short-change the long run but to mortgage tomorrow to juice up today. I for one do not presume we’re too smart to know better; why should we be? Dewey beyond a reasonable doubt did it, and whether or not you personally believe them to be an outlier, governments, financial institutions, corporations, and households around the world were (we know now) doing it throughout the first decade of this century. I would not be shocked were some law firms to fall into the same beguiling trap.

But that’s actually for another day.

Let’s put this into larger historical perspective.

Industries tend to follow quasi-biological life cycles of birth (invention/creation), childhood (halting steps), adolescence (self-discovery), rapid acceleration into maturity and supremely competent adulthood (what in ecology would be called the “climax phase”) and, yes, senescence and decline.

In terms of Law Land, a rough analogy is that Paul Cravath’s invention of his System a century or so ago represented our passage beyond childhood into adolescence, and that it’s all been one long, extended, increasingly glorious adulthood ever since, as we’ve refined and tweaked and buffed the model around the edges, making no material changes. And boy, did it ever deliver the goods, in terms of BigLaw growing as a share of GDP and PPP growing in relation to the average worker’s earnings. And it worked for virtually everyone who’d climbed aboard the bus, whether they were terribly introspective and astute about what they were doing or not. Until about 2008, that is.

Now we’re in a transition phase, I believe, where a tremendous premium will be placed on firms’ ability to figure out their rightful place in this world, and clear blue water will begin to appear between firms who go on to ever greater strength and those who find themselves relatively marginalized and, yes, irrelevant.

We are scarcely the first, nor will we be the last, industry to go through this life cycle.

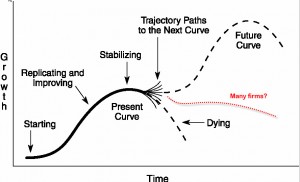

Indeed, this life cycle is so well-known that it has been diagrammed, and it’s called the “S-Curve.” Here it is:

(Image courtesy CEO ThinkTank.)

I submit we may be approaching the fraying ends of the “Present Curve,” where the “Next Curve” is indistinctly and dimly not quite yet in focus.

What determines the speed with which clients adopt the “next curve?” Three primary factors, none of which bodes well for those wedded to the status quo:

- Relative superiority: How much better is the new than the old? Many clients seem to think the old is not great.

- Complexity vs. simplicity: Is the new difficult to use or adopt? Given that clients are largely driving it, I’d have to guess not.

- Awareness: If no one has ever heard of the “next thing,” good luck with it. Everyone has heard of LPO’s, alternative fees, etc.

To be clear: I do not envision this as the phase-jump from circuit boards to microchips, analog to digital, or CRT to flat-panel, where the original incumbent was supplanted in its entirety. No. Law firms as we know them are not going away.

Rather, I see this as a jump from a world where merely to be a conventional law firm was to live at the climax stage of the “Present Curve,” into a world where performance of some firms will vault onto the “Future Curve,” while that of others (most?) will follow the irresolute trajectory I’ve depicted with the red dotted line.

Why, you might be asking yourself, would any rational firm choose—and it is a choice—to stick with the declining model?

Now, this may not be an answer, but it’s a reality: Firms in every industry do this all the time. Perhaps the most well-known recent excavation into how this happens was Clayton Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma but I recently discovered an even earlier and at least as nuanced a treatment of the phenomenon in Peter Drucker’s Innovation and Entrepreneurship (1985). The following excerpts are from his chapters on “Industry & Market Structures” (pp. 76 et seq.) (all emphasis mine).

Industry and market structures sometimes last for many, many years and seem completely stable. … Indeed, industry and market structures appears so solid that the people in an industry are likely to consider them foreordained, part of the order of nature, and certain to endure forever.

Actually, market and industy structures are quite brittle …

In industry structure, a change requires entrepreneurship from every member of the industry. It requires that each one ask anew: “What is our business?” And each of the members will have to give a different, but above all a new, answer to that question.

…

A change in industry structure offers exceptional opportunities, highly visible and quite predictable to outsider. But the insiders perceive these same changes primarily as threats. The outsiders who innovate can thus become a major factor in an important industry or area quite fast, and at relatively low risk.

Drucker also identifies “near-certain, highly visible indicators of impending change in industry structure,” which include:

- Rapid growth and the success of existing practices, “so nobody is inclined to tamper with them” despite their becoming obsolete;

- A tendency to become complacent and above all to “skim the cream;”

- A tendency to define and analyze the market based on history and not reality.

And this from “Hit Them Where They Ain’t” (pp. 220 et seq.):

Some fairly common bad habits that enable newcomers to use entrepreneurial judo and to catapult themselves into a leadership position in an industry against the entrenched, established companies:

- “NIH,” or not invented here; because we didn’t think of it, it can’t be of great value;

- Again, the tendency to “cream” a market, that is to get the high-profit part of it, which is always punished by loss of market and trying to get paid for past rather than current contributions;

- Even more debilitating, according to Drucker, is the third bad habit: the belief in “quality.” “Quality” in a product or service is not what the supplier puts in. It is what the customer gets out and is willing to pay for. A product is not “quality” because it is hard to make and costs a lot of money; that is incompetence. Customers pay only for what is of use to them and gives them value. Nothing else constitutes “quality.”

- The delusion of the “premium” price. A “premium” price is always an invitation to the competitor.

Harsh words, harsh advice? Indeed.

Yet firms once upon a time as distinguished as RCA, Xerox, Bell Labs, US Steel, Westinghouse, Kodak, Honeywell, and countless others have failed to learn these lessons at their peril.

This is not the type of history we should want to repeat. So what now?

Plenty of folks are happy to tell you (for a fine sum) that the answer is (pick one):

- (a) to get global, and fast, preferably by merging on payment of a “success” fee;

- (b) to adopt a single-minded laser focus on what you do best;

- (c) to double down on client service;

- (d) to go the boutique route;

- (e) to become an exquisitely talented maestro of assembling just-in-time teams you put together for one project at a time, with the precise blend of talents, capabilities, and capacities to get the job done and then to disperse (think producing a Hollywood movie or constructing a major downtown office building);

- (f) to relentlessly pursue the top right quadrant of that handy two-by-two matrix and spurn all but the most high value, premium, price-insensitive work (this is a perennial entrant in the strategy race);

- (g) and surely there are other configurations I’ve missed.

My own idea is somewhat different.

We have no idea yet what BigLaw will look like in the future, and the only way to find out is to invent that future.

Please take this as a gravely serious observation, not flippant or glib in the least.

Remember what Drucker said about each firm having to find its own (new) answer as to what it’s business is. Time for creativity, imagination, innovation. Try things. But don’t try one big thing, try lots of little things. Don’t put all your chips in the center of the table; learn as you go along, make midcourse corrections, seek continuous feedback, react. As Air Force fighter pilots have been taught since the days of the Korean War, in a dogfight you have to observe the “OODA” loop:

- Observe your environment;

- Orient yourselves towards your clients and competitors;

- Decide what you’re going to do right now;

- Act

- (Repeat)

Grand plans don’t perform well in midair, and it may feel to some of us as if we’re being thrown into midair. Nimbleness, decisiveness, and immediate readjustment perform much better.

Step back: Imagine someone presenting you 10 years ago with a slim plastic/metal slab slightly longer, narrower, and much slimmer than a pack of cards and asking you what you would like such a device to do if you could carry it around in your pocket or purse all day long? I suspect most of us—most assuredly including yours truly—would have had not the remotest idea. Tell time? Play music?

Or, far more historically profound, recall your high school or college biology and learning about the Cambrian Explosion. Some 650 million years ago life on Earth changed in ways never seen before or since: All the major phyla and forms of animals we know today suddenly appeared; we went from “almost nothing to almost everything, almost overnight,” as one biologist put it.

Two critical points: First, no one saw it coming (assuming the counterfactual that there had been anyone to observe it beforehand); and second, it involved wildly unbridled trial and error, with far more extinctions than successes. Yet the successes were world class: Limbs for locomotion, eyes and ears, digestive and reproductive systems and the start of organized neural networks to mastermind it all.

I think we may be at a similar turning point. It’s time to experiment, folks, to learn from what fails and what succeeds, and to invent our futures, even though we have no idea what it will look like yet. This is not optional; it is the signal challenge confronting us. It’s not too much to say that if we don’t get this right, nothing else matters.

Because if we don’t do this, someone else is going to do it for us and to us.

Let’s get to work.

Not sure what the online equivalent of giving a speech a standing ovation, but that’s the feeling I wish to convey at the end of this series. Superb.

And I’m not sure what the online equivalent of toasting you for that kind remark is, but that’s the feeling I have at the moment! Sincerest thanks.

Bruce,

I read all 12 installments of your series with great interest….twice. This is an extraordinary body of work that reflects enormous insight and ought be required reading by every managing partner of every law firm, or professional services organization, in the world. You do a very effective job of challenging the status quo and your series is something between a call to arms and a much-needed wake up call for our profession. As always, I plan to share many of your insights with my partners. And I plan to cogitate over many of your proposed initiatives.

Brad

Brad:

As always, your thoughts are deeply appreciated. Your comments are frankly quite touching.

I’m quite passionate about these things so very glad, and ever so slightly relieved, to know others pick up on that.

All the best,

Bruce

(Editorial note: Brad Karp is the Chair of the Firm at Paul Weiss.)

Great read. I feel the transformation of the status quo begins in law school. There are groups of law students that acknowledge the industry’s course must change. These students desire to work for and start firms that embrace “change.” However, connecting with these types of firms is another challenge entirely, because even mentioning this “legal renaissance” immediately puts you on a type of interview black list–for most firms.