Before the New York City school system intervention by Al, the more sophisticated students and their families could “game” the system by strategically misrepresenting their preferences, and fully one-third of students ended up paired with a school they had not expressed a preference for at all. After Al’s system was introduced, participation rates climbed to near universality, the opportunity for strategic gaming disappeared (stated otherwise, the dominant strategy was to state one’s true preferences), and the number of students unmatched with a preferred school dropped to about 3% (they were then handled administratively). Needless to say, the system remains in place.

How about matching medical students with hospital residency opportunities? If this sounds like matching law students with law firms, it should.

Nearly three years ago, Prof. Ashish Nanda at Harvard Law School wrote History Rhymes, which proposed adopting a similar matching algorithm to pair students and firms in Law Land.

What problem was the medical matching system supposed to solve? Actually, the way the medical student/hospital recruiting market used to work was remarkably parallel to how the law student/law firm recruiting market works today: There was a terribly powerful dynamic pushing all involved to be “first:”

- Hospitals wanted to interview the “best” medical students first;

- Medical students wanted to interview the “best” hospitals first; and

- Medical schools wanted their students to be interviewed first.

It reached the point, right after World War II, that hospitals were sending out offers to medical students two years in advance of their residency by telegram at midnight on a certain day and students were required to respond by telegram, by noon that same day.

Quaint technology aside, sound familiar?

Key is to understand that no one involved really enjoyed, desired, or even benefited from this market dynamic. But each individual participant was pursuing what seemed in their best individual self interest. What everyone ends up with, however, is one enormous negative-sum arms race. Everyone is actually worse off, after great expenditures of money and anxiety.

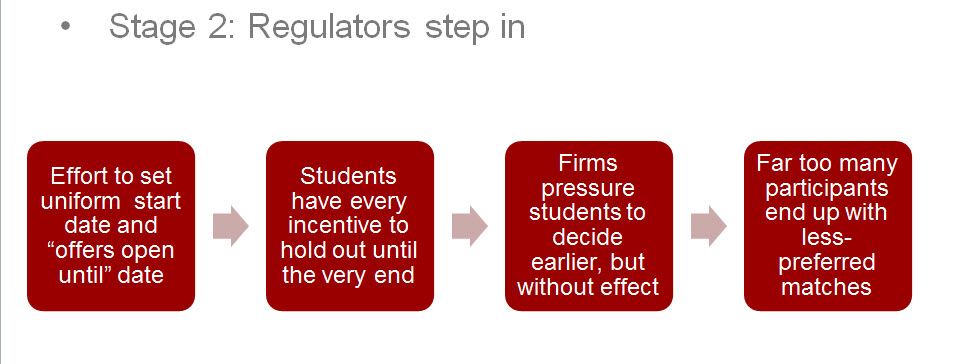

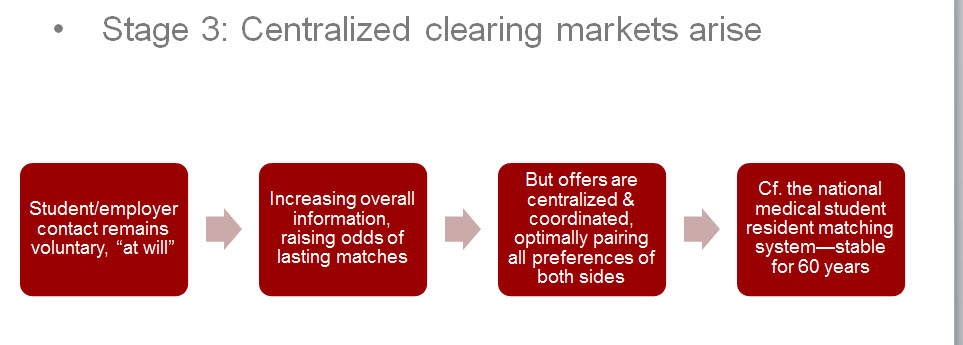

One of the primary sources of systemic market breakdown such as this is that the market is decentralized. Thanks to Al and others, the toxicology of decentralized markets is now much better understood. It goes like this (click to enlarge any image–opens in new window):

Again, is a centralized market really the answer? Here’s the data:

- The medical student matching system (technically, the “National Resident Matching Program”) has endured for over 60 years

- 37,556 applicants

- 4,176 employers

- 25,520 matches (2010 figures)

- The National Bureau of Economic Research found over 100 markets organized with a central clearinghouse, only three of which had abandoned the clearing system (and found that all three were due to sui generis exogenous factors—indeed, the paper is titled, The Collapse of a Medical Labor Clearinghouse—And Why Such Failures Are Rare)

A bit more on how the “NRMP” works: After students and hospitals get to know each other through free market, bilateral searches by students for residency programs and by hospitals for candidates—followed by mutually agreed meetings and interviews—students enter their rank-ordered list of preferred hospitals into the matching system and hospitals do the same with their preferred lists of students.

On a single “Match Day” each year, typically in March, the algorithm runs. Students learn which hospital they’re going to and hospitals learn which students they’re getting.

Need the match be mandatory?

In some cases, actually, it’s not; for example, an experimental program being developed in Pennsylvania to recommend matches between foster parents and adoptive children will leave the final decision to the parents and social workers. But it’s a tremendous advance from complete dysfunction and chaos.

In the case of the (mandatory) NRMP, because the resulting matches are optimal and “stable” in the rigorous sense described above, the system has endured in concept (technology has of course evolved) since the day it was implemented after World War II.

And why shouldn’t centralized matching yield a stable, equilibrium solution for these previously dysfunctional markets? They’re merely benefiting from Nobel Prize winning insights.