If you believe the structural environment for BigLaw hasn’t fundamentally changed since 2008, the series I’m inaugurating today is not for you. (I would also have to ask, from a mystified perspective and in the kindest of ways, if you’re paying attention?)

Call it the Great Recession, the Great Reset (my favorite), or whatever, the world palpably shook in September 2008 and the repercussions are still very much with us.

Herewith, then, the first in a series on Growth is Dead.

Today we’ll be talking about pricing pressures. Future articles will address, at least:

- Excess capacity

- The proliferation of career tracks

- Partner expectations

- Lateral partner mobility

- And the critical role of truly strategic thinking

Yes, many of these topics are deeply interconnected. For example, pricing pressure and excess capacity (see: Microeconomics 101), or partner expectations and lateral partner mobility, but I think they’re sufficiently distinguishable to be worth analyzing in separate articles.

I look forward to your thoughts, suggestions, and comments—and if there are one or more topics you’d like me to add to the list, please suggest them in a comment to this piece or a private email to me.

First a bit of background

Let’s begin by rehearsing some baseline, but critical, data. If we don’t all agree at the outset on some of the patient’s symptoms, we have no prayer of agreeing on a diagnosis.

I have borrowed heavily in what follows from the Hildebrandt/Citi Private Bank 2012 Client Advisory, since it has the following virtues: (a) it’s as current as anything available; (b) its sources are actual firm financials, not wistful beauty-contest aspirations; and (c) it’s publicly available so open to critique and correction.

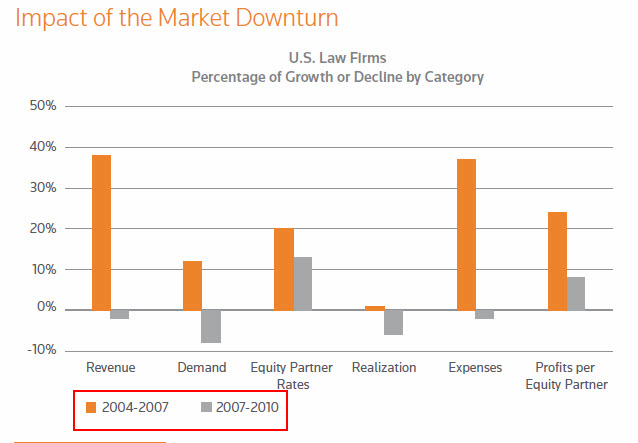

Let’s start with an overview of the growth, or decline, in key financials comparing the period immediately before the meltdown with the period immediately after.

If you want to deny things have changed, you would point to Equity Partner Rates and PPEP, but for purposes of this discussion I disagree. The time series I would call out are Revenue, Demand and Realization – all down. I focus on those three series because equity partner rates and PPEP are internal financial reports essentially under the control of firms (at least in the short run, and three years still qualifies as the short run). The ones I prefer to focus on are creatures of the market and reflect market forces.

Lest you protest that partner rates being up displays a “healthy” trend, let’s look more closely at realization.

Any way you want to look at it, this tells a dramatic and—if you’re rooting for BigLaw, alarming—story. By the way, the definition of “collected realization rate against standard” is the percentage of work “performed at a firm’s standard rates that is actually billed to and collected from clients.”

We are collecting, industry-wide, less than 85 cents on the dollar. Imagine another industry that (de facto) gave its average customer a 15% discount day in and day out. We would immediately, and correctly, leap to the conclusion that one or both of two things are true about that industry: It’s charging too much or it’s delivering too little.

Remember this is an average: Are you thinking that you and your firm are in the blessed minority for whom this isn’t true? If that’s what you’re thinking (and if it’s honest to God true that your firm is healthily above these lines), then bully for you.

But, folks, for every reader knocking on wood that their firm is above these lines, there is, statistically speaking, another reader whose firm is below these lines.

I’ve written recently that I believe never before have averages been so misleading, and I would like to reaffirm it here for the record.

We’ll get to why strategy, and differentiation, matter more than ever, but that’s towards the end of this series. For now we’re talking about the industry writ large.

Pricing Pressures

Simply put, clients are pushing back as never before. Among other things, they are:

- serious, for the first time, about alternative fee arrangements, caps and blended rates, rate freezes, and so on

- strongly resisting—even refusing—paying for junior associates

- requiring that major segments of a matter, be it litigation or transactional, be handled by LPOs, staff/contract/temp lawyers, or anything other than full-time partner-track associates.

Don’t take my word for it. Here are two remarks managing partners have made to me in the past few months:

- “What we used to assign a dozen associates to now only takes four” and

- “Raising rates? No problem; piece of cake. But raise rates 5% and realization drops 6%.”

We also see what I call “suicide pricing” in response to RFPs. These are bids—from name-brand firms, mind you—that are so breathtakingly low one wonders how they could possibly make any money. The short answer is they can’t. These bids come in 5, 10, 20, 40% under what my clients think would be reasonable for the matter. But in a desperate and/or deluded attempt to keep the factory whirring away, such bids are calculated and submitted in the full light of day.

Rarely do I adopt this posture, but permit me through the wonders of the online medium to prostrate myself in front of you and beg your firm not to engage in suicidal pricing. Why not?

- The immediate result is that you will, by hypothesis, lose money on the deal. Best avoided.

- A medium-term result is that you will, as department stores succeeded in doing to the industry’s systematic ruination, train your clients never to purchase services from you except when you offer them drastically discounted: “40% off sale.”

- The final and long-term result is that you have single-handedly devalued what your firm can offer in the eyes of your clients. Kiss goodbye to any fantasy of aspiring to the “high value, price-insensitive work” that everyone and their brother thinks is their firm’s rightful entitlement. The psychology is not obscure: If you [clearly] don’t much value what you do, why should I?

Finally, I did a tour of duty as an inhouse counsel (here in New York at then-Morgan Stanley/Dean Witter) and I have news for you: Good clients do not want trusted law firms to lose money. They really don’t. They want you around for the long run.

Part of achieving that, being around for the long run, will involve conquering the pricing pressure dragon. Not every firm will.

I would bet that the collected realization rate would be even lower if there were a way to take into account work actually performed by attorneys that was not recorded for firm billing purposes to keep invoices within client expectations (and/or realizations within internal firm expectations).

I’m looking forward to the next post, which may answer this question, but:

There’s an obvious tension between clients’ demands for lower rates and their willingness to hire firms other than the tried-and-true Biglaw firms. How do you think this tension will play out? To what extent do you think clients will be willing to give up their obsession with firms’ brands and actually hire uppity new entrants into the legal services marketplace?

I understand your warning to established firms not to become bargain-bin legal services providers. But as you observe (I think), something’s gotta give.