Welcome to the second installment of “Growth is Dead:” Our topic for today is excess capacity.

Let’s start with overall supply of new lawyers, which is the font of everything else.

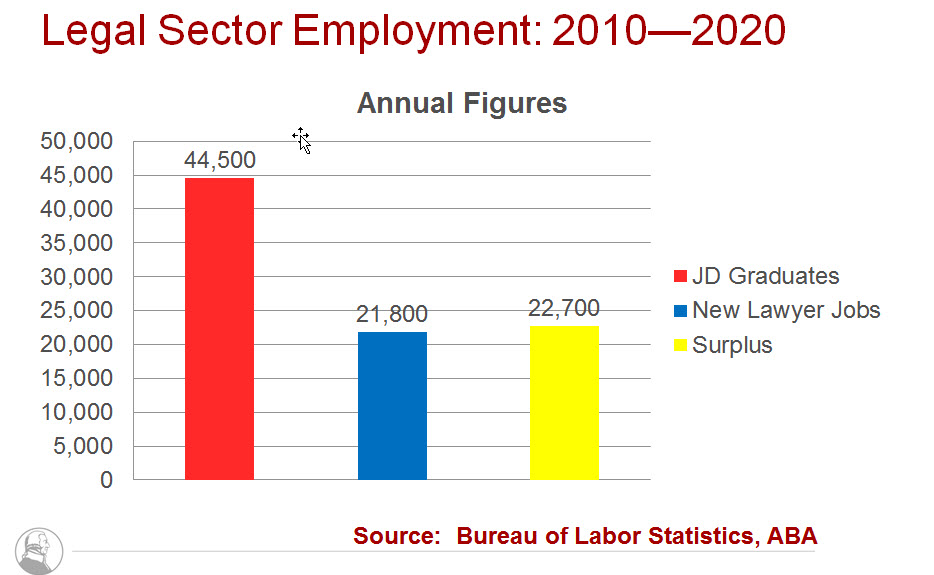

Thanks to the redoubtable Prof. Paul Campos (University of Colorado Law), we have a comprehensive summary of a combination of the best available numbers from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics and the American Bar Association, we learn that:

- Between 2010 and 2020, the US economy will produce 218,800 job openings for lawyers and judicial clerks, or a little under 22,000 per year

- These statistics include filling the slots of retirees and other job force departures as well as new job openings

- They’re based on historically “normal” 10-year business cycles, so if you believe we’re in a long-term and slow employment recovery, they could be overestimates

- US law schools granted 44,004 in 2010, which rose slightly to 44,258 in 2011 and 44,495 in 2012

- As they say, “do the math:” 132,757 new JDs in 3 years would fill 61% of all available lawyer jobs for the next decade

- And there’s no obvious end in sight; law schools are cash cows for their universities (or themselves, if unaffiliated) and no individual school has an incentive to cut enrollment barring some highly improbable pact surmounting the “collective action” psychological and economic barrier. (Yes, some pathbreaking schools such as UC Hastings/SF, under the leadership of Frank Wu, are breaking from the pack, but they’re countable on the fingers of one hand.)

Graphically, it looks like this—every year for the next 10 years:

The next step is to examine the supply/demand landscape more specifically for BigLaw.

Here, NALP always has the most comprehensive and thorough statistics. From their “Perspectives on Fall 2011 Law Student Recruiting” and from a presentation Jim Leipold (NALP Executive Director) delivered in New York earlier this year:

- “Law firms continue to bring in small summer classes, barely increasing class size from recession-era lows.”

- Structural changes include greater competition from LPOs and offshore firms

- Lawyer jobs increasingly are being lost to technology

- Compared to pre-recession numbers, there are significantly fewer private practice jobs-down by 10% just from 2010 to 2011

- With a 20% drop in average salaries

- Leading to higher law graduate un- and under-employment

- Fewer law graduates overall are working as lawyers

- New grads are competing with displaced lawyers

- Salaries for new grads actually employed as lawyers – be the measure median, mean, or “adjusted mean” (a NALP statistic) are down about 12% in one year.

Now, all this has addressed the macro environment for lawyers in general and BigLaw in particular.

But in microeconomics, “excess capacity” has a slightly different—and more pointed—meaning as applied to specific firms within a pertinent market segment, and it’s to that I now wish to turn.

Notice I said “pertinent market segment.” I would argue that the market for BigLaw services (or SophisticatedLaw services, perhaps more accurately) is in all ways that matter a market segment distinct from US national economic demand for “lawyers” in general or legal services in general. From that perspective it actually doesn’t matter much to BigLaw whether there’s a pervasive oversupply of lawyers in the 50 States; it matters whether BigLaw itself has excess capacity.

And does it ever.

Managing Partners tell me this, other consultants are telling this to the media, and it seems universally recognized. We have:

- too many associates given what clients are willing to pay for

- too many of-counsel and non-equity partners, who are clogging the advancement pipeline for those below them, and

- in many firms, too many equity partners, if judged on rigorous performance criteria (or if simply judged on the number of equity partners Firm X can support at the PPEP to which it has become accustomed).

This is not those people’s fault.

It’s the result of the historic path our industry has taken over the past 30 or so years, growing like clockwork at high single-digit rates, and never before September 2008 having experienced a sustained, systemic, enduring, macroeconomic downward shift in demand for our services.

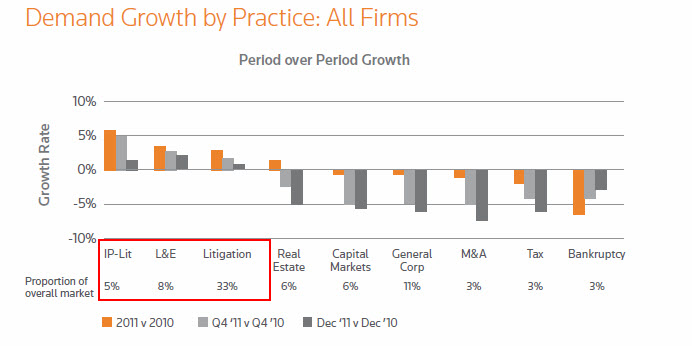

Don’t take my word for it. Here are the latest numbers from the Citi/Hildebrandt 2012 Client Advisory on demand “growth” (or lack thereof, obviously) by key practice areas:

Here’s what stands out to me:

- Pretty much across the board, demand is continuing to fall:

- Dec ’11 vs. Dec ’10 is the worst time series (dark grey right-hand bars in each triplet)

- Q4 ’11 v. Q4 ’10 is the second-worst time series (medium grey middle bars), and

- 2011 v 2010 is the “healthiest” series (left hand dark orange bars)

- The two areas growing fastest—IP litigation and labor & employment—together make up only 13% of law firm revenue, while the six shrinking segments account for 32% of revenue (note that the practice areas displayed account only for about 75% of total revenue, presumably because displaying them all would require more detail than would be useful)

In terms of excess capacity, falling demand is a classic, and usually the #1, driving component. After all, firms don’t usually overhire recklessly or build new factories before they have customers, so purposefully creating excess supply is extremely rare and I would hazard never intended.

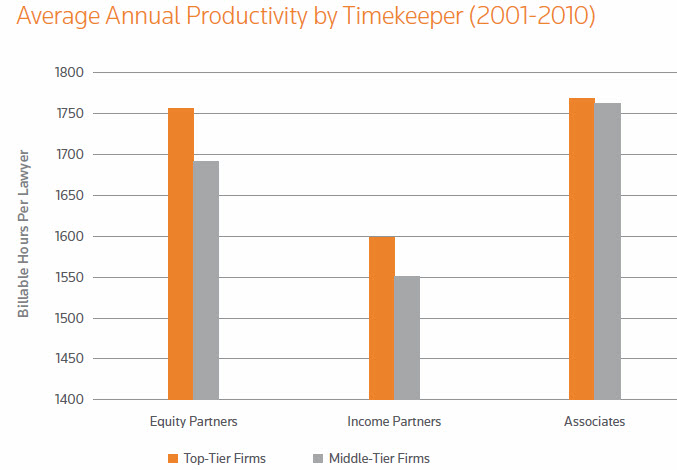

Now let’s turn to “productivity” (for another day is the debate over whether the word “productivity” is an inapt, if not distorting and insulting, name for gross billable hours, but everyone seems to know what it means and we will, for today, stick with it):

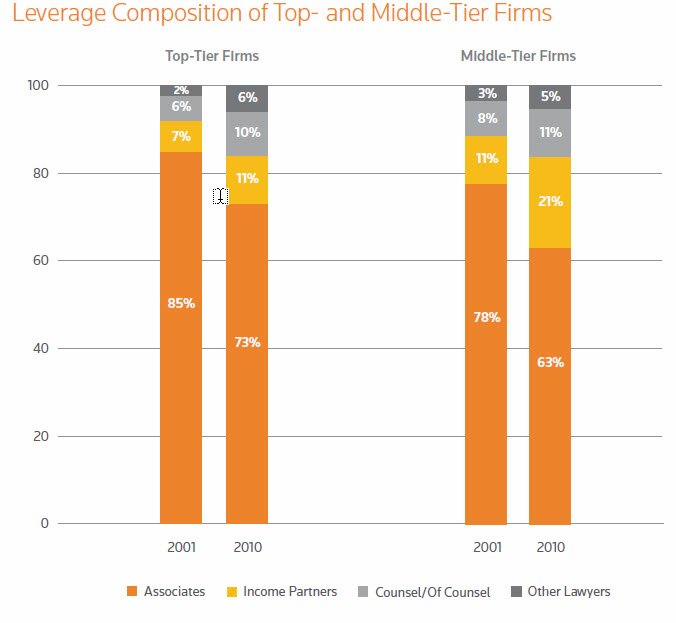

We have to look at this in conjunction with the evolving composition of timekeepers to gather the full story. Here’s that data:

Putting these two charts together, here’s what we’ve been doing to ourselves: We have systematically increased our reliance on the most expensive, least productive cohort of our lawyers. This is not the behavior of rational firms doing all they can to increase their value to clients.

(Disclaimer to non-equity partners reading this: The last thing I’m saying is that you don’t contribute value, and the last thing I’m saying is that you don’t work hard. All I’m saying is that among your counterparts in the non-equity partner law firm productivity food chain, you work fewer hours and cost the firm, and presumably clients, more.)

But we’re talking about excess capacity.

Firms in an industry with excess capacity face an almost irresistible compulsion to cut prices, even to unprofitable levels. The goal is simply to keep people busy, in service of keeping the firm alive and satisfying clients, and in the hope that once market conditions recover, everything can get back to normal.

A hyper-rational manager might argue that cutting costs to the level that matches revenue is the only path that makes sense, and (rationally) that’s correct, even inarguable. But that’s hard, because the vast bulk of the costs in a law firm are people, starting with lawyers and starting among lawyers with partners and the most expensive non-partners.

And because it’s hard, by and large that’s not what we’ve done. Nor, I might add, are we remotely at risk of aping hyper-rational managers.

So we are faced with excess capacity. Which leads to intense pricing pressure. Which leads to lower profits. Which leads to:

I leave it to your imagination.

I think your analysis is sound, but I take issue with your claims concerning income partners and their productivity. Today’s income partners were yesterday’s rising associates. Your interpretation is that something — perhaps the lack of ownership or upward mobility — causes an entire class of productive attorneys to become relatively unproductive. Another interpretation is that the equity partners are reluctant to introduce income partners to clients because those individuals compete with the equity when it comes to client relationships, and such concerns are non-existent when it comes to the associate rank-and-file.

Thanks for your ongoing thought leadership, Bruce!

Best,

Maggie

An argument can also be made that work is shifting to the highest value attorneys, to the benefit of clients. Income partners tend to be highly experienced and skilled, particularly in comparison to the median associate (1 income partner hour may be worth 5 junior associate hours for many tasks), yet income partners also tend to be cheaper than the average equity partner. The result is fewer untrained lawyers churning the files.

Surely as long as our education systems continue to oversupply this problem will never disappear. In the UK the education system is quite slow to respond to the demands of society for different careers, not just in the legal profession, but across all sectors, preferring to churn out graduates in as large a volumes as possible, regardless of the requisite requirements of industry.

Until our governments employ joined up thinking to encourage a “quota” system for each particular industry, we will never produce the appropriate numbers of qualified people to fill the available jobs.