Last week we published a column noting that today “discussion of incentives often begins from the false belief that only cash can influence behavior.”

This remark—the heart of the piece in as few words as possible—prompted a regular reader to offer a comment so compelling that it’s worthy of reprising and expanding upon in a column of its own; this is that column. The reader, who I know, is an engineer, which will become clear momentarily.

In opposition to the belief in cash as incentives , our friend wrote that “Once – and not that long ago – the motivation would have been based on honor, and that notion of honor would have been widely understood and acknowledged.”

He proceeds to relate the tradition (hitherto unknown to me) of the “iron ring” given to all engineers upon graduation from Canadian universities.

The tradition dates to the collapse of the Quebec Bridge, a span across the St. Lawrence River between Quebec City and Levis, Quebec, Canada, while still under construction in 1907. Proposals to bridge the river were considered in 1852, 1867, 1882, and 1884 before finally being approved in 1897.

By 1904 construction was well underway but preliminary engineering calculations on stress and load-bearing had never been properly re-checked when the design was finalized—at substantially greater length than originally proposed. As a result, the actual weight was to be well in excess of its carrying capacity. As completion neared in the summer of 1907, engineers noted distortions of critical structural members already in place. Despite warnings which were mailed (not telegraphed) by the lead engineering firm to the construction manager, skepticism prevailed (including the suggestion that the beams in question were bent before they were installed) and only after another round of discussions did word finally come down to halt construction.

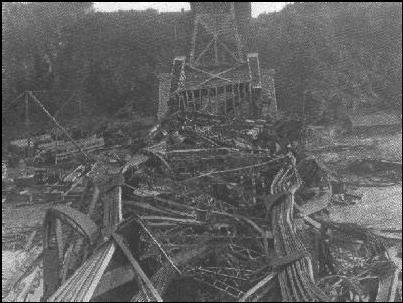

Too late. After four years of construction, the south arm and part of the central (cantilevered) span of the bridge collapsed into the St. Lawrence in just 15 seconds, killing 75 of the 86 workers on the bridge that day.

The iron ring ceremony incorporates a composition by Rudyard Kipling:

Gold is for the mistress – silver for the maid!

Copper for the craftsman cunning at his trade.

“Good!” said the Baron, sitting in his hall,

“But Iron – Cold Iron – is master of them all!”

Kipling also alluded to the New Testament story of Martha and her children who continued doing the household chores needed to keep things running rather than sitting at the Lord’s feet, and approvingly compares the “sons of Martha” to engineers.

Originally the rough iron rings were composed of iron from the failed Quebec Bridge, but in the century since that has shifted from reality to symbolism, yet the rings remain rough and unfinished, not to be in any way confused with adornment or jewelry.

Our reader continues the story:

The ring is small and very plain – not a piece of jewelry. It is worn on the little finger of the working hand, so that as the engineer writes or drafts, the resistance of the rough ring moving across the paper will remind him/her of the need for care. Although the ring ceremony and wearing of the ring is not a requirement for the PE in Canada, every engineer I know who graduated from a Canadian university has the ring, and almost all of them wear it regularly. The final part of the tradition, which I very much like, is that one returns the ring to the association on retirement, and families do so on death.

Our profession has no equivalent, and we are immensely poorer for it.

Symbols matter.

There’s the tangible and the immanent, the quotidian and the aspirational, the meretricious and the virtuous.

Can we still tell the difference? Do we care, or even have the self-awareness left to know, which we are pursuing as a profession?

You have to wonder:

- Law schools have—deservedly—come in for withering media coverage over the past year and more, for practices ranging from aggressive interpretations of the truth to flat deceit; some believe the industry needs a wholesale house-cleaning;

- Federally funded student loans have been pivotal in greasing the skids of law schools’ expansionist tendencies over the past decade and more, and many wonder if educational debt is the financial equivalent of the next housing crisis, yet the industry seems to power on regardless of the human toll inflicted on optimistic borrowers now finding themselves facing a protracted future saddled with non-dischargeable debt;

- And we ourselves, BigLaw, have demonstrated we can distort reality in service to the basest of short-term gratification, while our addiction to lateral partner hiring, with all its unintended-but-universally-recognized toxic consequences, has never been greater.

Have we, I repeat, lost our way as a profession?

Speaking of symbols, here’s another one that speaks unforgettably to the difference between merely surviving to fight another day vs. attaining something difficult and worthy: The years I ran the New York City Marathon, the organizing body, the New York Road Runners Club, had psychological counseling stops every few miles along the route, together with the obligatory medical/EMS tents. I assume the EMS teams had every state of the art technology available to them, but the psych teams had no tools save one: Small 2-inch long snippets of the neon orange finish-line tape.

Runners having a tough time would get a pep talk, sure, but also a tangible symbol of what they were striving for: the tiny piece of orange tape which they could hold in their hand, stuff in their shoe or their waistband, and which would (we all hope) carry them over the finish line.

Lawyers have no equivalent of the iron ring, or the scrap of orange tape.

We need one, and it can come none too soon.

A regular reader and friend, who’s both a lawyer and armchair economist and, even more germane for present purposes, a partner in a Major Canadian Firm, wrote me as follows. I reproduce his remarks with permission but also honoring his request for anonymity:

______________________

You make a great point that our profession could use a symbol to remind itself of its ideals and goals. In Canada, litigators still have a form of this, as we still gown for court and call ourselves Barristers and Solicitors. Luckily we do not wear wigs, which English Barrister friends tell me are itchy and hot and get vile over time.

We often invite top American litigators to assist us in our litigation skills training programs. We rent gowns for them so that they can feel the part. Most seem to like the tradition and some have asked if we believe that it contributes to civility within the Bar. Personally, I think that it does, as it reminds you that you are an officer of the court, and not just a hired gun for your client. American lawyers who observe our ways note the relative civility in our courts compared with their own. As you say, symbols are important, and perhaps our robes do an effective job of reminding our litigators of their obligations to the court and their chosen profession. Robes have the side benefit of levelling the field, so to speak, as everyone looks the same and $5,000 suits and $200 suits hang in adjoining lockers in the Barrister’s changing room lockers. The one minor debit of this tradition is that clients pay for the time we take to robe before appearing in court and then disrobing at the end of the day, but typically we discuss the case during this time, so that time is not entirely wasted.

My brother-in-law is a professional engineer, and he wears the iron ring, so I have been aware of the engineering profession’s tradition for many years. As I am a product liability lawyer, I work closely with professional engineers and the vast majority wear the iron ring. We have a few lawyers at [the firm] who are also professional engineers. They typically don’t wear their iron rings unless they are attending an event where other engineers are likely to be present. It is a discrete form of identification to aid in picking out the other professional engineers at a cocktail party.

__________

Following an additional exchange, he added:

__________

The engineers at [the firm] are also debating whether it is fact or fiction that the iron rings continue to be made from girders from the failed bridge. There are supporters for both views. Certainly, when the tradition started, they were made from the failed bridge’s girders.

One of our Ottawa engineers mentioned that annually he participates in a half marathon race in Quebec City crossing the re-built bridge. As a runner, I thought that you might be interested in knowing that a race crosses the rebuilt bridge.

My faithful Canadian correspondent adds more material about the ring:

_____________

A further comment from a partner in our [major Canadian city] office, who just returned from vacation, and who got an engineering degree [from a school in British Columbia]:

When I graduated in 1981, I was told the rings we received were made from the steel girders from the collapsed section of the Second Narrows Bridge (now called the Ironworkers’ Memorial Bridge) which occurred in 1958. The bridge connects Trans Canada Highway #1 from Burnaby over to North Vancouver. I expect that the Engineering Universities in each geographic region of Canada claim to have their engineers’ rings forged from a local bridge disaster.

I have always been impressed by the incorporation of such symbols into a profession, whatever that profession may be.

Even if I know next to nothing about that profession, upon first impression what it at least shows me is that the profession is worthy of respect as it has certain ideals that its members strives towards.

I myself am a recent Engineering and Economics graduate from a well known American university but unfortunately, nothing was given to us in such a symbolic manner upon graduating.

Maybe we could take a page or two from the book of our friends up north.