The National Law Journal just published a wealth of information, derived from NALP statistics, about which law schools send the greatest number of their graduates to NLJ 250 firms as first-year associates, and-this is the really fun part-how many graduates of those schools make partner at NLJ 250 firms (for symmetry, think of this as “first-year partners” by law school).

Because we love data, this provides an irresistible opportunity to examine some sacred cows.

First out of the blocks this morning was Viva Chen (The Careerist) with “Too Good for Big Law,” noting among other things that Loyola/Chicago law grads made partner at a much greater rate than University of Chicago grads, with their presumptively far superior pedigrees.

The always-insightful Prof. Bill Henderson (Indiana/Maurer law school, and himself a University of Chicago law grad) hypothesizes that despite-or because-it’s far harder for graduates of non-elite schools to get in the door of BigLaw to begin with, they don’t take the opportunity for granted, and are far more willing to put nose to the grindstone and strive, no matter the personal cost. Indeed, they may not even perceive it as having “a personal cost;” they consider themselves lucky to be where they are and will be d***’d if they’ll let it slip through their fingers.

Bill calculates, for a few name-brand schools, the ratio of new hires into the NLJ 250 to graduates from those same schools making partner in the NLJ 250.

Obviously, and before the dinging email bell starts clanging, no, it’s not technically accurate to use same-year data for both measures since there’s a lag of nearly a decade between “first-year associate” and “first-year partner,” but since it’s unclear that ignoring the lag skews the data favorably or unfavorably for any school or cohort of schools, we’re going to plunge ahead.

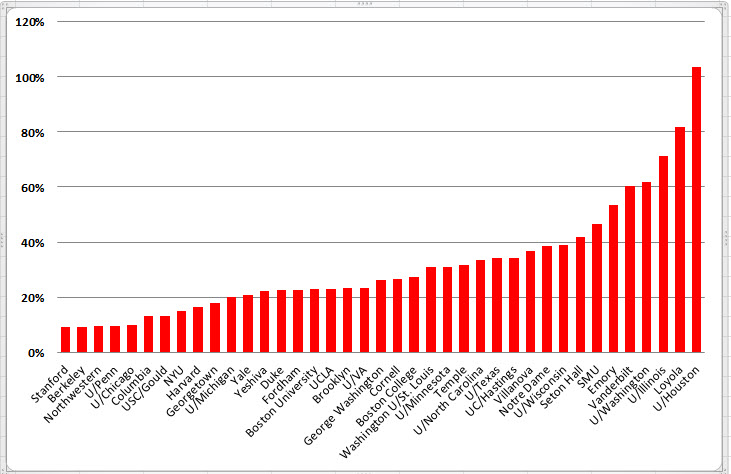

We did the analysis for all the schools where the NLJ published both first-year associate and first-year partner data, and here’s the answer in vivid form:

This shows the percentage of graduates from each school making partner as a share of all graduates from that school who started as first-year associates. (Again, this only includes schools where the NLJ reported both data series.)

Since it’s virtually impossible to read, here’s the data in tabular form:

| Stanford | 9% |

| Berkeley | 9% |

| Northwestern | 9% |

| U/Penn | 10% |

| U/Chicago | 10% |

| Columbia | 13% |

| USC/Gould | 13% |

| NYU | 15% |

| Harvard | 16% |

| Georgetown | 18% |

| U/Michigan | 20% |

| Yale | 21% |

| Yeshiva | 22% |

| Duke | 22% |

| Fordham | 23% |

| Boston University | 23% |

| UCLA | 23% |

| Brooklyn | 23% |

| U/VA | 23% |

| George Washington | 26% |

| Cornell | 26% |

| Boston College | 27% |

| Washington U/St. Louis | 31% |

| U/Minnesota | 31% |

| Temple | 32% |

| U/North Carolina | 33% |

| U/Texas | 34% |

| UC/Hastings | 34% |

| Villanova | 37% |

| Notre Dame | 38% |

| U/Wisconsin | 39% |

| Seton Hall | 42% |

| SMU | 46% |

| Emory | 54% |

| Vanderbilt | 60% |

| U/Washington | 62% |

| U/Illinois | 71% |

| Loyola | 82% |

| U/Houston | 104% |

Regular readers know I went to Stanford, which finishes first and worst in this sorting, so for the next year I expect a pass on being accused of self-interested bias.

The powerful message this data delivers is, to me and putting Stanford aside, how many elite schools perform really poorly on this critical measure.

In fact, the Top 14 numero uno elite schools almost, in and of themselves, constitute the 14 worst-performing schools. This is quite a coup on their part, I’d say. The only two schools of the Top 14 in the conventional rankings who are not in the Top 14 on the above Hall of Shame Washouts listing are U/Va (#19) and Cornell (#21).

Now, is this data flawless?

Hardly.

You can criticize, among other things:

- Pretending the 10-year time lag between 1st-year associate and 1st-year partner doesn’t matter

- Speculate on whether the Great Reset has made it harder than it ever was for non-elite school graduates to get into BigLaw to begin with, which would imply that the number of 1st-year “non-elite” associates is depressed at the moment, whereas the number of non-elite 1st-year partners is exaggerated because 10 years ago more people who could fog a mirror were being hired

- Point out that we’re dealing with pretty small numbers for a lot of these schools, so random year-to-year variations can drown out the signal with noise (parenthetically, this certainly feels like it’s true with respect to the University of Houston, our #1 winner on this scale, where a miraculous 104% of 1st-year associates made partner)

- And I’m sure there’s more I’m missing.

But please, disorienting as it may be to your world-view, take at least 60 seconds to reflect on these numbers. They tell a shockingly consistent story about the performance in The Real World of graduates of our elite law schools.

I close with an excerpt from a review of David Halberstam’s The Best & The Brightest (1972), his magisterial post mortem on the Vietnam War:

Unlike those of us who actually saw the jungles of Vietnam up close and personal, these men were neither ignorant, nor provincial (at least not in the ordinary use of that term), nor poorly informed; rather, they both considered themselves and were considered by others to be the most outstanding, capable, and effective members of the contemporary “Power Elite” i.e. the best of the then contemporary ivy League graduates Kennedy could lure from the bastions of the academic, business, and corporate world into the magic and presumptuous world of Camelot. In essence, these guys were seen as the best and the brightest of their generation. Just how their elite educations, presumptuous world-views, and de-facto actual ignorance and lack of what we would now refer to as “street-smarts” led them to conclude it was in the nation’s interests to fight what others have called “the wrong war in the wrong place with the wrong foes at the wrong time” is an epic tale of arrogance, insular thinking, and mutually sustained delusions.

Fortunately life and death aren’t at stake in obsessively recruiting only from “Tier 1” schools. Just vast amounts of resources and plain old common sense.

I think this data gives some very interesting directional information, and the easily grasped chart is fantastic.

It shouldn’t be confused with a longitudinal study, though. The more highly ranked schools send a proportionately higher percentage of graduates to clerkships and other elite government jobs, and they don’t show up at the entry level (making their effective percentages even lower).

More importantly, on the flip side, it treats partnership as if associates start big law firms in a tournament to make partner, and that’s really a deceptive metaphor. They start big law firms to make real money now and gain human capital, and once they have it put it to use in diverse settings including law firms (including law firms other than where they started), in house departments, investment banks, private equity firms and teaching law school. Some of those alternate employers are even more brand conscious than law firms (for example, law schools, with Yale and Harvard dominating law faculties). The bias applies in house, as well. I have a friend, a lower tier school graduate, who turned down top ten schools because of financial considerations, and while she made GC of a publicly traded company she had to defend her degree at every job change, even well into a spectacularly successful in house career. Associates with misgivings about big firm practice who come from high ranked schools might find it easier to move to other attractive employers, and might find it advisable to make the move before they get anywhere near ten years in. It might not be just drive (although that makes sense); it might also be opportunity.

The data also lumps together all AmLaw 250 firms as if they were a single entity, and that’s far from true. Packing the partnership of Cravath with your graduates is a different thing from packing the partnership of a regional firm far down the list. It also treats AmLaw 250 firms as the law firm destination of choice, and that’s far from obvious.

In short, if you were looking at law school as a ticket to a career, this data only helps a little. You would really want data that takes into account whether making partner at an insurance defense firm at the lower end of the AmLaw 250 represents a better career option than teaching law school, doing M&A at an investment bank, working in a great in house department, or working at an elite small firm like Bartlit Beck or MoloLamken.

This data does dovetail with some of the work Bill Henderson is doing at LawyerMetrics, however. Fancy law degrees, high grades based on once a semester written exams, and 30 minute interviews turn out to be very imperfect predictors of performance.

Chris Zorn massages the data in his own way over at Empirical Legal Studies (http://www.elsblog.org/the_empirical_legal_studi/2012/03/blog-roundup-pedigree-and-performance.html) and concludes essentially in the same vein I do:

“So, while the data are noisy, the larger pattern still holds: More elite schools have consistently lower “partner yield rates” than do less elite, tier-one schools. While this doesn’t begin to get at the various reasons why this might be happening, it does lend some support to the idea that there’s something here worth looking into.”

Thanks, Chris!

I’m no statistical guru, but doesn’t the metric subvert its inquiry?

Top-14 schools send proportionately more graduates into NLJ-250 firms. And don’t even the snobbiest firms value variety in their snobbery? In other words, if there are five partner positions available, wouldn’t they want at least three or four law schools represented? I’m genuinely asking; I don’t understand these things.

But, if there are 30 Harvard grads gunning for five spots, odds are 1:6. Not good for any single alumni. If there are two Lyola grads gunning for five spots, odds are 2.5:1. It would be surprising if one of them *didn’t* make it. This presumes my assertion about valued variety.

In other words, in order for the metric to reveal something qualitatively useful for deciding where to go to law school, then (1) the process from associate to partner must be purely meritocratic and (2) every associate must be trying for it.

Fact is, your still more likely to get your foot in the door from a top-14 schools. And if you never get your foot in the door, I doubt you’ll make partner.

On the flip side, if you can kick As and finish in the top ten of your third-tier school… but that’s seems like a bigger if.

Not saying it’s a useless metric. On the contrary, it’s very interesting.