The title, “muscle memory,” I owe to Prof. Bill Henderson of Indiana/Maurer School of Law in Bloomington. Bill-and now I-use it to describe how the habits law firms learned during the boom years have carried over into the present reality, as inapt, maladaptive, self-defeating, and potentially mortal in their repercussions as they are.

To recap the bidding: From approximately 1980 (Reagan, Thacher, the introduction of the PC, globalization kicking in for real, the slaying of the inflation dragon) to September 15, 2008, BigLaw was on a toboggan to the sky. Compound annual growth rates of 6-8-10% in revenue seemed our birthright, and so long as costs didn’t get wildly out of control (see: Finley Kumble, Brobeck) and the partnership managed to stay roughly aligned (see: Coudert Bros., Shea & Gould), managing a law firm amounted to obeying Hippocrates’ “first, do no harm.”

No more.

Adding to the Citi “flash” 2011 report is the Hildebrandt Institute’s future-looking 2012 report (confusingly co-branded with Citi) foreseeing “yet another year of limited growth in 2012,” which turns out to be a euphemism for flat to down, certainly on an inflation-adjusted basis.

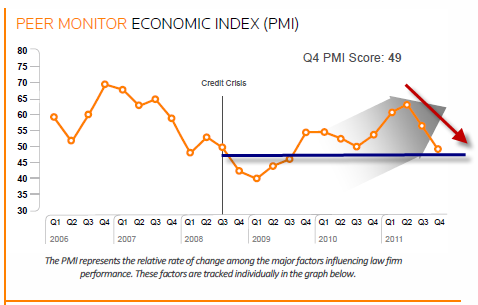

The PeerMonitor Index for the 4Q of 2011 has more negative news, starting with the simple fact that its Q4 performance was “the worst in over two years.” There’s more:

- Realization hit a new historic low;

- Demand weakened in every quarter, turning outright negative (an absolute decline, that is) in Q4;

- “Stated” rate growth stalled, meaning that real rates faced “a troubling trend.”

And yet we retain the muscle memory of those fabulous decades, as managers, somewhat disoriented in that what we got so accustomed to doing now seems to lack the direct drivetrain connection to growth that it used to have.

Of course, there are degrees of disorientation. Some are dealing with this step change superbly, with adroit and new dance steps never seen before; most are muddling through with midcourse corrections and half-measures; and a few remain in comfortable denial, holding their breath until it’s 2006 again. The first group deserves to be taxed heavily needs no help from us, and the third will find history deals harshly with those implacably on the wrong side of the market. But the middle group is intrinsically interesting, as they are struggling, valiantly for the most part, with challenges they never signed up for.

I’m not going to proffer unsolicited advice today about what the middle group should be doing, although the management literature is replete with commentary, perspective, and even a few wise observations about how to run firms in mature industries—that is to say, industries whose future growth is largely a one-to-one reflection of GDP growth. Rather, I’m going to offer some observations about just how hard it is for successful firms to actually change.

[And before you start carpeting the comments with observations about the growth prospects of BigLaw, let me hasten to add that there is surely one area where we can thank our lucky stars, and that’s the insatiable desire and truly impressive talent of politicians worldwide to make regulations more and more and more complex. The US tax code alone is reputedly more than 70,000 pages in length. The substantive part of Sarbanes Oxley was a few pages at most, and Dodd Frank in its online version is over 2,300. If you want to put existential threats in perspective, recognize that we are not the newspaper industry.]Conveniently, The Atlantic just published a column on “Why Companies Fail,” and the message for us couldn’t be more clear: “Change is risky, after all, since it definitionally involves doing something that isn’t already working.” Pithier it does not get.

But not to be dismissive: This is as serious a topic as can be, since we’re talking about enterprise mortality. The article takes GM as a “peg,” but GM is hardly alone:

Over the past few decades, GM’s ability to resist change has proved almost uncanny. Why did the company wait so long and do so little—not once, but time and again—before finally falling into bankruptcy? And what, if anything, does that portend for its future? The questions go beyond GM, a company that’s hardly unique. Why did Blockbuster idly watch Netflix destroy its business? Why did Kodak let digital cameras drive a once-mighty industrial giant into penny-stock territory?

Ask Jeff Stibel, and he’ll tell you: because that’s what troubled companies do. Stibel, once an aspiring cognitive scientist in Brown’s graduate program, is now a serial entrepreneur who has led turnarounds at Web.com and Dun & Bradstreet Credibility Corp. “Once the human mind has set out to do something, or has gotten in the habit of doing something,” he told me, changing it is “very hard.” When you add group dynamics, it’s even harder. You don’t need to be a brain scientist, of course, to know that people resist change … and yet, even knowing that, you’d be surprised at how many firms keep driving toward inevitable disaster at top speed. GM’s record is very much the norm, not the exception.

So widespread is this phenomenon that there is even a “Turnaround Management Association,” and Thomas Kim, one of its executives, observes that the situation tends to be dire in the extreme before firms are ready to admit they could use a little help:

“Typically, a company doesn’t pull someone in until they’re on the brink of disaster. They can’t make payroll, can’t make a loan payment, or can’t pay off their loan that’s coming due.”

Can this possibly be rational? Haven’t we all had it drilled into us that humans are risk-averse, and losing one’s job or equity position sounds like a large risk to me?

The problem is there’s another dynamic at work.

Even a dysfunctional culture, once well established, is astonishingly efficient at reproducing itself. The UCLA sociologist Gabriel Rossman told me, “If new entrants assimilate to whatever is the majority at the time they enter, and if new entrants trickle in slowly, then the founding culture can persist over time, even if over the long run they make up a tiny minority.” This is why Americans speak English even though more of us are ethnically German or Yoruba. In linguistics and sociology, it’s known as the “founder effect.” In corporations, it’s known as “how we’ve always done things.”

Recurring to the “muscle memory” of the boom years: Two conspicuous results of the homing instinct compelling a return to those glory days are (a) the highly charged lateral recruiting market; and (b) merger mania. The American Lawyer continues to report ever higher record activity in lateral partner moves among the AmLaw 200, while Hildebrandt notes a 67% increase in completed mergers involving US firms in 2011 over 2010, and predicts 2012 will equal or exceed that number.

I believe both have reached frenzied levels, in a pained search by law firm leaders to deliver the customary results. I used to look skeptically (to be charitable) on firms that proudly boasted of increased revenues when, adjusted for increased lawyer headcount during the timeframe in question, was unimpressive or negative. Now those boasts have become so common as to foreclose commentary on each and every one.

For rank and file partners, again accustomed to the clockwork 6-8-10% annual upward boost in PPP and distributable income, suddenly being told that the firm is marking time can come as a rude surprise. Most partners, after all, are rightly focussed on serving clients and do not pay day to day attention to the economics of BigLaw.

This can create toxic fallout, however. Partners can fear their firm is losing ground, or falling behind, or ceding territory. This perception is wrong, but at a certain level it’s also understandable. Managing partners and executive committees need to nip it in the bud. How? Simply by educating partners about how the landscape has changed, and how maintaining market share and not-shrinking revenue and not-shrinking PPP are The New Normal.

This can be an arduous and thankless task, but it’s the one facing management today. We need to re-educate a generation of partners who have never experienced anything else about the new reality.

Of course, the widely reported industry-wide summary de-equitizations may smooth your path. That’s the good news buried inside the bad.

I have just caught up on several articles together – including both your Growth is Dead pieces, Lateral Hiring = Zero Sum Game, and Slater Gordon / RJW articles.

Taken together they make a depressing read for Law Firm partners, and give me only limited pleasure in saying – at last it’s here – I have not been dreaming for the last 18 months.

As my own presentations have been saying for some time there is going to be major consolidation- even more so here in the UK- I even coined the term “3 year half-life” (The top 1000 will be 500 in 3 years, and only 250 in another 3 years). On this basis, if i am right 75% of current firms will have been merged out of existence (or worse) in 6 to 8 years.

In which case however unpalatable the side effects of lateral hiring – the alternatives may be even worse.

Jerry Kowalski’s description of how firms unwind will be played out many times in the next few years.

The point you did not make is that for firms who start to wobble, the only way that they can get back on track is either to hire laterally, or to acquire teams or firms.

But they suffer the “Groucho Marx” syndrome. The only firms (and lateral hires) that would want to join us, are firms that we would not want.

So no wonder Managing Partners keep running ever faster – at least they stand still that way.

Some may simply be hoping that they survive long enough for the inevitable to happen on their successor’s watch.

It’s not going to be pretty, and it is certainly a risky time to be over extended.

So who has the nerve to be innovative now?

And lastly – congrats on the new look

Barry Wilkinson – Wilkinson Read & Partners