In “Idea or Product?” I wrote about the difference between organizations that basically view themselves as creating products vs. organizations that see themselves as loyal to an idea.

I’m happy to report that the piece generated more than its share of commentary.

As has become customary with the Adam Smith, Esq. community, through some form or another of the invisible hand of spontaneously self-organizing behavior, comments all but invariably come directly to my inbox as private emails; if I want to republish them, which I often do, I religiously seek permission and offer anonymity, and again, both those conventions are universally followed. I have theories about why this is so, but I’ll spare you all since I’m not a social anthropologist.

One of the comments came from a regular correspondent who pointed out that in my original piece I treated organizations asymmetrically. That is to say, I focused on the “demand” side of what they do (what they deliver to their customers) and not on the “supply” side of where they get the resources they need to meet demand.

In Law Firm Land, our supply is simple: Talent.

So the question du jour is: How might one apply the paradigm of an “idea focused” organization to the talent side of the equation?

I’ll share my own ideas on this, and then we’ll bring in the big guns–McKinsey.

For me, organizations that have an idea focus are far more stimulating places to work than firms with a product focus. As I said in the first piece, products come and go, but ideas evolve and endure.

More important, if you’re like me, what really motivates you to go to work every morning isn’t the money. Hasty caveat: Yes, the money has to be reasonable and it has to be fair. But as I’ve observed before, if someone says they switched firms for 15% more, they’re fibbing: Something else was going on.

What motivates you is believing you’re making a contribution to an institution that makes sense: That is to say, an institution with intrinsic value today and challenging aspirations about what it will be in the future. Not to be too metaphysical about it, but an institution that at some level makes the world a better place, or at least provides something that would be missed were it to no longer exist.

What’s seriously unmotivating is working in a place that provides fungible products or services, if for no other reason than this: Organizations tend to be symmetrically idea- or product-focused, on both the demand and the supply sides. I don’t know if this is a law of nature or of Management 101 (most likely neither), but as a generalization it strikes me as legitimate. Companies creating fungible products tend to employ fungible people–or at least people they view as fungible–to accomplish it. Companies pursuing ideas distinctively their own find and/or require similarly distinctive people, and distinctive individuals in turn tend to gravitate towards places with clear identities which people can articulate and largely agree on.

Now let’s hear a few words from McKinsey. This comes from their “Organizational health: The ultimate competitive advantage.”

It starts with defining terms, and from the premise that:

Organizational health is about adapting to the present and shaping the future faster and better than the competition. Healthy organizations don’t merely learn to adjust themselves to their current context or to challenges that lie just ahead; they create a capacity to learn and keep changing over time. This, we believe, is where ultimate competitive advantage lies.

And they announce at the outset that what “organizational health” means depends on the organization:

Nor should you study what other companies do and then apply their approach. While you can always learn helpful things from others, we have found that the recipe for excellence in a particular organization is specific to its history, external environment, and aspirations, as well as the passions and capabilities of its people. Creating and sustaining your own recipe–one uniquely suited to these factors–delivers results in a way that your competitors simply can’t copy.

Around now, you’re probably asking yourself (as am I) just what precisely constitutes “organizational health.” Alas, our authors neglect to define it. (Maybe they want you to buy their book to find out.)

But let’s proceed on the generous impulse that you intuitively can identify healthy vs. sick organizations and see what we can learn. More strongly, I would ask you to assume that “organizational health,” as McKinsey calls it, is what I’m referring to as an idea-driven organization on the talent side.

With that assumptive clarification out of the way, shall we proceed?

In terms of demonstrating a correlation between organizational health and performance, I found the following graphic compelling, because the results are across different teams within the same organization–so something “local” is clearly going on:

This shows that the correlation (not causation, obligatory disclaimer) between “organizational” health and performance accounted for 54% of the variation. That’s a very large effect. And it supports my thesis that motivation towards an organizational goal–an “idea”–matters.

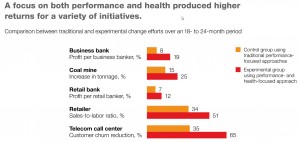

The authors performed the same trick at “a large financial services institution,” choosing an experimental and a control group that were comparable (net profit before taxes, customer economics, branch staff characteristics, and so forth) and followed them over 18 months while the control group went through a “sales stimulation program” using traditional methods and the experimental group followed an approach emphasize performance and health.

The difference? An 8% gain for the controls, a 19% gain for the experimentals. Here are the results from more industries (yellow = control, red = experimental):

Let’s assume you’re persuaded. Now what are you supposed to do?

Recall how we got here: I made the assumption–call it heroic if you’re so minded–that what McKinsey is calling “health” is what I’m calling an idea-driven organization in the eyes of its talent.

If you’re with me on this, then the path from here on in is all an inviting gradual procession from one logical step to another. Since they’re consultants, McKinsey has come up with a memorable (well, that’s in the eye of the beholder, actually) five-step process, which they label:

- aspire

- assess

- architect

- act

- advance.

In our terms, aspire means nothing other than defining the “idea” by which your organization’s talent should be driven. What precisely is that idea? Where, in other words, do we go from here?

Assess is the gimlet-eyed task of determining, without sugarcoating or unwarranted optimism, what your firm is capable of achieving. What attitudes, assumptions, or mindsets might be holding you back? How can you rip them out root and branch?

Next is the clunkiest of the five monikers, architect, which in a right-thinking world would never have slunk into its louche alter ego as a verb, but all it means here is what do we have to do? And not only do, but create incentives for people to do. (Remember, you get what you pay for.) This is the nuts and bolts step where you have to no only make sure people know what the idea is (#1 above) and that your firm is capable of achieving it (#2), but that people are motivated to pursue it.

Act is blessedly straightforward. You have to manage your way from here to there, or at least from here to the continuously evolving pursuit of there.

Finally, advance acknowledges that an idea-driven talent organization will forever–thankfully–be a work in progress. This isn’t a one-time event, or even a one-time three-year or five-year plan, perish the thought. Rather, it’s all about your firm embarking on a commitment to continuing, yes we dare say perpetual, improvement in pursuit of the evolving notion of The Idea which is at the core of attracting, retaining, and motivating your talent.

So there you have it, all tidily wrapped up with a bow. Except.

What’s missing?

The hardest part.

What is the motivating idea for your talent?

What is the defining idea for your clients, for that matter? (They’re mirror images.)

Those of you who read closely and have high recall know that in my original “Idea or Product” column I asked readers to contribute their nominees for idea-based firms. To date, I’ve received a grand total of one response, which follows, and which is therefore by definition the most interesting (the reader requested anonymity):

Baker & McKenzie – In all

humility, having been at Baker for close to 40 years, and having known Russell

Baker, this firm was based on Russell Baker’s idea that globalization would bring the need

for globalized legal services, that these services are best performed by

globalized locals, not transplants sent out from the headquarters. Yes,

some Firms are more profitable for a year or two. Some have fed off of

high revenues from booms in tech, m & a and specialty litigation. And some

have higher PPP. But nobody else is based on the idea that being global and

local at the same time is a formula for success. Writing this on the day that

our former chairman, Christine Lagarde, takes the reins at the IMF, gives me

special reason to write this. And believe me, sticking with an idea in the face of all

the negative chatter (which seems to have finally subsided a bit) is not

always easy.

We’re not here to debate this nomination; I think our correspondent makes a fair point, and he states the platform he’s writing from at the outset.

Rather, the shocking thing to me was this was the only firm anyone nominated.

Are we so poverty-stricken as a profession and as an industry when it comes to motivating ideas?

Suffice to say that I do not like where the evidence seemingly wants to lead me.

But the business of ideas is the business I’m in.

Shall we talk?