This is a tale of how this is not your father’s recession.

About a year ago I read Reinhart and Rogoff’s This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, which ably–and depressingly–provides chapter and verse on how the aftermath of financial-crisis-driven recessions is far uglier and longlasting than the aftermath of garden variety manufacturing or consumption or even price shock-driven recessions. Looking back over financial crises for which there is plausible data, they conclude, among other things, that severe financial crises leave in their wake:

- Real housing price declines of 35% over six years

- Equity price declines of 56% over 3.5 years

- A spike in the unemployment rate of 7 percentage points over four years

- Output declines of 9% over two years

- And government debt exploding an average of 86% in real terms (a combination of collapsing tax revenues and counter-cyclical fiscal policy, combined, often, with rising interest rates)

I’d like to book-end (no pun…) these historical observations with an admirably succinct summary of what’s going on with unemployment from Foreign Policy, written by Tyler Cowen and Jayme Lemke: “10% Unemployment Forever?” What’s to explain? Simple: The recession has formally, technically, been over since June 2009 but unemployment has barely budged. What, we may all be forgiven for asking, is going on?

Let me interleave excerpts from the Foreign Policy piece with some charts and, of course, my own thoughts. All charts are courtesy of the wonderfully rich Calculated Risk. Emphasis in the FP piece is supplied.

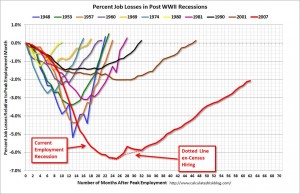

First, how does this recession compare with other Post-WWII recessions in terms of unemployment?

If you weren’t impressed (or depressed) with the strength of this recession, perhaps now you are. There have been 11 “official” recessions in the US since WWII, and in all but one of them the percentage of job losses had fully recovered by now.

Here’s what FP has to say:

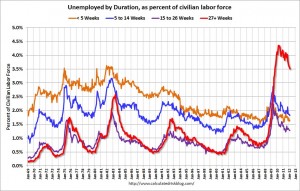

We are, sadly, in a very deep pit when it comes to the labor market. The recent private-sector estimate from ADP Employer Services announced the creation of 297,000 new jobs for December [2010], but this is the first instance of a real dent in the jobless rate since the beginning of the recession. The November report from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics pegged the unemployment rate at 9.8 percent, which translates to over 15.1 million unemployed. Over 40 percent of currently unemployed workers have been out of a job for over six months, the highest percentage of long-term unemployment since World War II. The numbers look even worse if we consider the underemployed, which includes potential workers who have given up looking for a job or the 9 percent of the labor force that is made up of part-time workers who would prefer to be working full-time. At least 2.5 million people gave up looking for work in the last year alone.

But the official unemployment rate, as measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, paints a rosier picture than the prototypical Person in the Street would think is quite fair.

As noted, workers who are involuntarily part-time aren’t counted at all. Here’s what that looks like (time series starts in January 1960 and the left vertical scale is thousands of workers):

Then there’s the human tragedy–there’s no other word for it–of the “long-term” (> 6 months) unemployed. Again, the time series starts in January 1960 and the left vertical axis is thousands of workers:

Back to the FP:

Even if the December rate of job creation continues, it will be 2014 before unemployment is down to 5 percent. […]

So what happened? Why have American labor markets ended up in such a dire situation?

The simple Keynesian explanation for the initial unemployment is that aggregate demand — the country’s combined spending and investment — has been too low. But it’s unlikely that spending is the only problem, as unemployment is too high and too persistent relative to similar episodes of disinflation in recent history. If weak demand was the main problem, profits should be collapsing too, but they are not. Investment and corporate profits have been fine for some time now, and they are broadly within the range of pre-recession estimates.

There’s a second problem with the Keynesian story, which relies heavily on the notion that real, inflation-adjusted wages are sitting at too high a level. If unemployment causes someone real suffering, why wouldn’t he or she be willing to take a lower salary to get a job and ease the pain? But rather than falling, private-industry wages are currently on the rise — up nearly 60 cents per hour since the end of the recession. There are plenty of good theories why it is hard to cut the wages of employed workers — long-term contracts pose legal challenges, and fragile worker morale threatens to collapse under the stress of wage cuts. But it’s harder to explain why unemployed workers can’t find new jobs for less pay, especially if output is recovering, profits are high, and corporations are sitting on a lot of cash.

Many conservatives in the United States have placed the blame for high unemployment on the shoulders of President Barack Obama, [which seems unconvcing]. And don’t go blaming job losses on illegal immigrants taking jobs from documented workers: Latino immigrants have left the country in large numbers since the start of the financial crisis.

As time passes, it is harder to avoid the notion that a lot of those old jobs simply weren’t adding much to the economy. Except for the height of the housing boom — October 2007 through June 2008 — real GDP is now higher than it has been in the entirety of U.S. history. The fact that the United States has pre-crisis levels of output with fewer workers raises doubts as to whether those additional workers were producing very much in the first place. If a business owner fires 10 people and a year later output is almost back to normal, it’s pretty hard to make the argument that they were doing much in the first place.

[Now I want you to reflect on how what follows might describe the dynamics at your firm–Bruce.]The story runs as follows. Before the financial crash, there were lots of not-so-useful workers holding not-so-useful jobs. Employers didn’t so much bother to figure out who they were. Demand was high and revenue was booming, so rooting out the less productive workers would have involved a lot of time and trouble — plus it would have involved some morale costs with the more productive workers, who don’t like being measured and spied on. So firms simply let the problem lie.

Then came the 2008 recession, and it was no longer possible to keep so many people on payroll. A lot of businesses were then forced to face the music: Bosses had to make tough calls about who could be let go and who was worth saving. (Note that unemployment is low for workers with a college degree, only 5 percent compared with 16 percent for less educated workers with no high school degree. This is consistent with the reality that less-productive individuals, who tend to have less education, have been laid off.)

In essence, we have seen the rise of a large class of “zero marginal product workers,” to coin a term. Their productivity may not be literally zero, but it is lower than the cost of training, employing, and insuring them. That is why labor is hurting but capital is doing fine; dumping these employees is tough for the workers themselves — and arguably bad for society at large — but it simply doesn’t damage profits much. It’s a cold, hard reality, and one that we will have to deal with, one way or another.

The coinage of “zero marginal product workers” is perhaps unduly harsh, but we all know that neither ability nor effort is evenly distributed, and somebody has to be at the left end of the productivity curve. Could we really have had “zero productivity” lawyers? Evidently, we did.

What’s my support for saying this?

Just watch (he predicted) how the financial numbers will come in when 2010 results begin being reported. My guess is that, to make a gross industry-wide generalization:

- Top-line revenue will be flat to marginally up or microscopically down;

- Profits, however, will be noticeably up–not in life-changing ways, but appreciably;

- And this magic trick will be pulled off largely on the back of increased revenue per lawyer.

Revenue per lawyer, or RPL, as regular readers know, is one of my favorite law firm metrics. For one thing, it’s very hard to game. Total revenue and number of lawyers are both pretty well defined (aggressive people could start playing with FTE’s, but it hardly seems worth the candle). Far more importantly, it serves as a rough and ready proxy for the overall quality of a firm’s work–its “non-commodity quotient,” if you will. If you doubt me, look at who shoots the lights out year after year on this metric: Wachtell. And employment firms typically bring up the rear.

But again, zero productivity lawyers? I think it’s possible we did: Not, note, zero revenue lawyers (if you billed one hour and collected 50% of it, you were by definition not a “zero” revenue lawyer). But zero or even negative productivity lawyers are entirely possible, when you consider the salary, benefits, training, and overhead costs, and the perennial talent of junior associates to produce massive writeoffs and writedowns of their billable time. I don’t want to limit the blame to junior associates: “Of counsel” and staff attorneys who are coasting, and senior partners well past their sell-by dates, can be even more costly offenders. Now, many of those people have evidently been wrung out of our systems.

This “cold, hard reality” is a large part of what constitutes The New Normal.

We have seen our industry adjusting to a new, lower-employment equilibrium, and ugly as it has been, we can take solace (or cold, hard comfort) in the reality that we are not alone.