Sometimes it’s the quiet, seemingly unremarkable, things that ultimately rear up and bite you. Here may, or may not, be one.

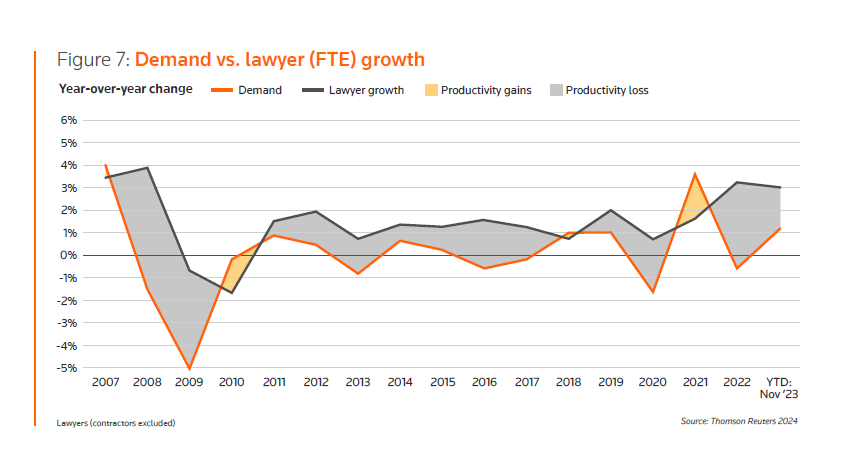

Let’s start with this chart from Thomson Reuters redoubtable annual Report on the State of the US Legal Market (here, the 2024 edition published some weeks back). If you actually pay attention to what the chart reveals, and don’t let your eyes—meaning your brain—glide over the familiar story it tells, it is nothing short of remarkable.

For the entire 15-yeare span of the chart, with two brief interruptions caused by extraordinary macroeconomic circumstances (the 2009 GFC and the 2020 pandemic lockdown), full-time lawyer headcount growth has exceeded demand growth. In other words, as the large swaths of light grey on the chart indicate, productivity per lawyer has declined consistently across the set of law firms that Thomson Reuters tracks.[1] I would be hard-pressed to cite another sector of the US economy of which you could say the same. In the modern era, labor productivity might briefly stagnate in some sectors but for it to consistently and substantially fall over such a long span of years has to be unheard of.

To give them credit, the authors of the report attempt to explain this most, shall we say, atypical data:

Since 2012, lawyer headcount growth has routinely outpaced growth in demand. In fact, only in rare cases has the opposite been true. This discrepancy is understandable as most law firms want to ensure they have the resources to meet unexpected spikes in demand growth such as occurred at the end of the GFC in 2010 and 2011. The downside of this strategy, however, is that this imbalance can place a drag on attorney productivity. For most of the past decade, demand has fluctuated between slight growth and slight contraction. At the same time, attorney headcount has grown relatively consistently, and at times quite aggressively. The result is many more attorneys vying for a share of work — a formula for declining per lawyer productivity. [TR Report, pg. 12]

To this economist, that strikes me—no offense to the estimable authors of the TR report—as less an explanation and more a restatement of the bizarre pattern of behavior law firms seem to have adopted. I can’t think of another substantial sector in the services economy whose behavior resembles this consistent and sustained pattern of growing capacity faster than demand.

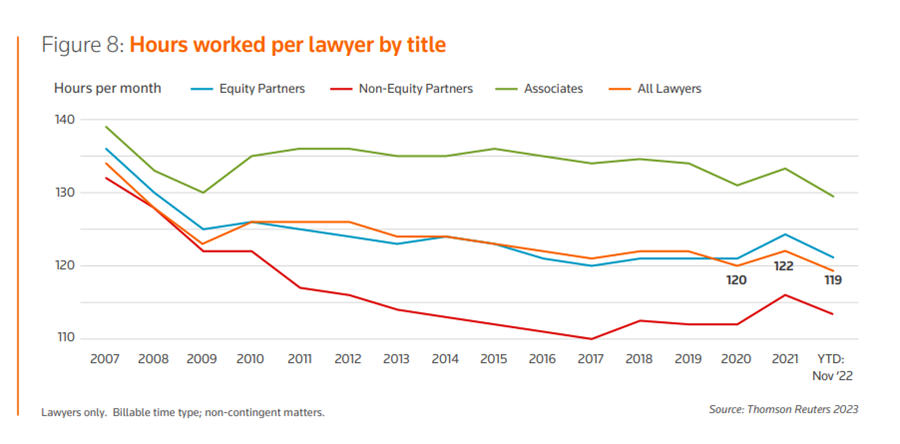

One logically possible explanation is that firms need more lawyers because the ones they have are working so much harder.

Well, guess again.

Here’s a chart (from TR’s report on this topic last year) showing “hours worked per lawyer by title” covering the same timeframe. Across every single lawyer title, hours have declined fairly consistently:

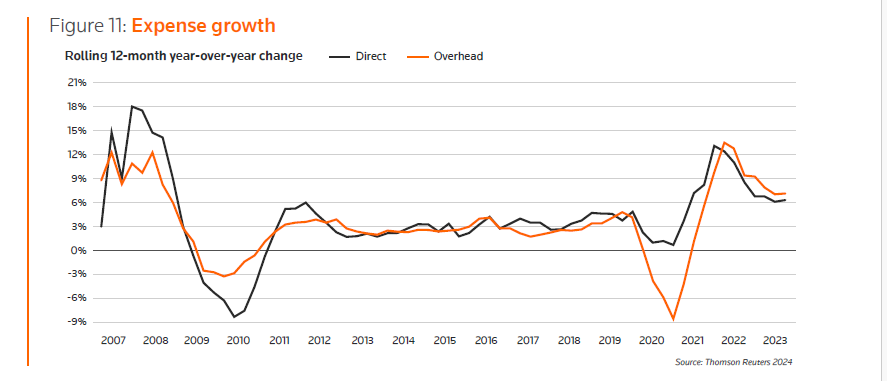

Indeed, the authors of the report single out capacity (headcount) growth as “the primary driver of aggregate direct expenses growth.” And here’s a graphic visual display of how that single factor—lawyer headcount growth—flowed through into overall expense growth:

This has consequences.

Among the most obvious—“self-evident” in fact—is one headlined in the “key findings” called out at the beginning of the report:

Sagging productivity and declining realization have combined to put a pinch on law firm profitability growth such that even the high pace of rate growth has been largely unable to remedy the situation [TR report at page 3, emphasis original].

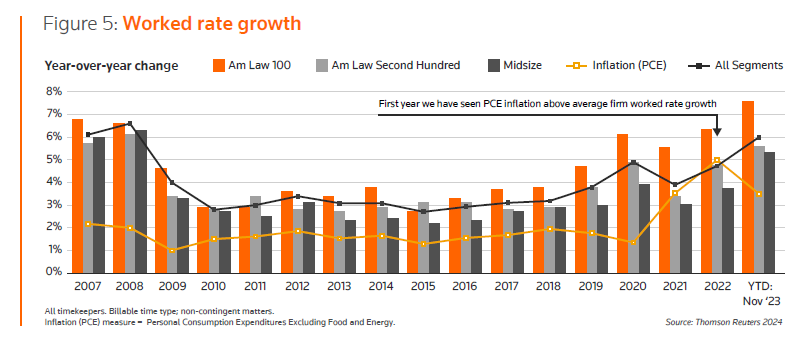

Of note is that last year appears to be one of the first periods in the 15 years of data Thomson Reuters provides where that was the case—”an occurrence never before seen in our data,” as they put it. For every other period, law firm rate growth comfortably outpaced inflation.

Take a look:

We’re almost done with this background, but bear with me through one more chart and a bit more narrative explanation of what I’m showing you including my own quick cheat sheet guidance on what Thomson Reuters’ terminology surrounding their various metrics for rates mean in economic and business terms.

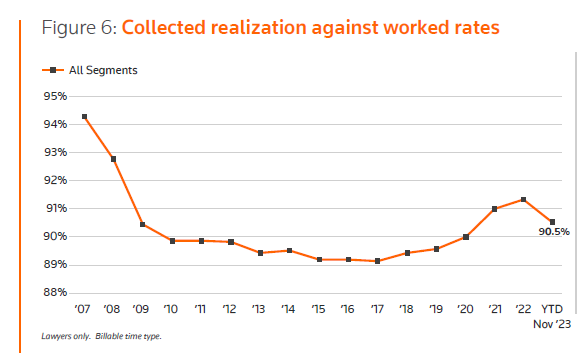

The chart we just looked at (“Worked rate growth”) shows, well, uh, rates, but rates are not cash in the door. Thomson Reuters knows this as well as you or I do, so here’s cash collected (“realized,” as they put it) as a percentage of rates over the past 15 years.

With the exception of a pandemic/lockdown-induced blip in 2021 and 2022, the indisputable message of the trend line is that law firms have been collecting about 90 cents on the dollar for well over a decade. This is not normal pricing behavior in a mature industry. Note—this is important, folks—that this is not data reflecting a single firm’s experience, which could be explained through any number of factors idiosyncratic to that firm and its client relations; this is an industry-wide, chronic and systemic phenomenon.

One might assume—it’s the logical place to start—that this severe pricing/collection haircut is at the request of clients. But no:

The positivity from rate growth, however, was tempered by the fact that, as rates grew, collected realization against those higher rates softened. By and large, that was not due to clients pushing back on invoices. Instead, it can be largely attributed to attorneys within the law firms proactively adjusting bills downward before they were sent to clients. This increase in write-downs resulted in a decrease in a metric known as billing realization. And as we’ve seen for several years now, as billing realization improves, so does the percentage of the worked rate the law firm actually collects, known as collected realization.

However, when billing realization declines, so too does collected realization. From at least the second quarter of 2022 through almost the end of 2023, law firm billing realization fell, ending the year with law firms collecting an average 90.5% of their worked rates. Recent stabilization in realization is encouraging, but realization remains 0.8 percentage points below its 2022 peak and more than a full percentage point down for the Am Law 100. [TR Report at 11-12, emphasis supplied.]

Put more simply, as an industry we seem irresolute about the value of the work we perform for clients. What if that insecurity is well-founded?

In a straightforward factual sense, this should not strike us as anything new; it’s not.

As we have noted, immediately following the GFC, client expectations for their outside law firms shifted toward demands for higher levels of efficiency, cost effectiveness, and predictability in the delivery of legal services. [TR Report at 23.]

In other words, we have been living through this disconnect between the “rack rate” price of the work we perform and clients’ perception of what they’re willing to pay (its worth or value to them) for 15 years.

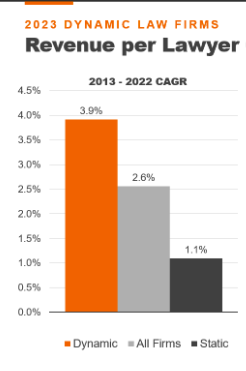

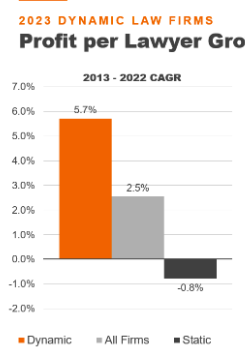

But all law firms are not performing equally by any means, which brings us to our final perspective on all this: Look at what TR’s so-called “dynamic law firm” analytic lens reveals.

The methodology they use is simple; they look at a decade’s worth of CAGR (2013-2023) for two key law firm performance measures: RPL growth and PPL growth. Law firms ranked in the top 25% on both metrics are deemed “dynamic” and those in the bottom 25% “static.” Here’s what those metrics show:

These superior results for the dynamic segment are, needless to say, no accident. Consistently over the decade we are looking at, they outperform the static segment in:

- Demand growth

- Worked rate growth

- “Fees worked” growth (total billable hours for a given period multiplied by the average worked rate)

- Productivity;

- And even lawyer headcount growth.

This type of outperformance cuts across all law firm size ranges, because it is driven by (relies upon) management acuity in reading the shifting dynamics of law firm market demand more astutely and nimbly than their competition, redeploying people and investments away from rate-challenged verticals and “following the money;” so, for example, in the long “Transactional Decade” of ca. 2010—2020, concentrating investments in professional and other resources there and away from litigation/disputes.

The dynamic leaders also pursued good old rational business hygiene more energetically than their lagging-performance competitors: Spending far more freely on technology, marketing and business development, and highly-qualified business professionals and support staff. Summing it up, the Dynamic firms were more businesslike, plain and simple.

About this time, you may be saying to yourself that this is a theme you’ve heard frequently here at Adam Smith, Esq.: A more businesslike approach yields superior business results.

Fair enough. I hope that everything in this column preceding this coda has demonstrated that to your satisfaction with numbers, charts, and graphs.

But what if superior financial out-performance is no longer “nice work if you can get it,” but an existential requirement? Enter Generative A.I. The annual State of the US Legal Market (2024) that we’ve been using as our jumping-off point for this column does add a coda on Generative A.I. in the form of three possible scenarios:

- The Rising Tide: Everybody wins: Clients get better advice faster and cheaper, law firms make more money from enhanced operational efficiencies and (they don’t say this but I take it as implicit) smarter “portfolio pricing.”

- A Lopsided Landscape: Clients win “at the expense of firms,” relegating outside counsel to rubber-stamp “final validation,” and substantially displacing/replacing law firms with software vendors and consultancies.

- No Big Thing: Generative A.I. in real-world deployment serves as KM with a college education and finds “utility in operations” but “does not notably change client benefits or firm costs.”

So what do I think?

(2) has never happened before in the history of law firm/client relations; why would we (really, people?!) expect it to start now? And I say this as someone who was in a client role for a decade.

(3) strikes me as absurd on its face. Generative A.I. may not be on the scale of Gutenberg but it ain’t word-processing. Come to think of it, it may end up being Gutenberg.

(1) the all-American born and raised optimist in me would like to root unreservedly for this scenario, but the lifelong student of economics in me warns, “Not so fast, pal, and not without massive and never-before-in-modern-history ‘transition costs.'”

Generative A.I. is too large a topic to leave here, and we will not do so. But as a survey of the law firm economic landscape on the cusp of being turned upside down, there you have our recap of last year’s financial results through the lens of 15 years.

Fasten your seat belts.

[1] The universe of firms Thomson Reuters tracked for purposes of their 2024 annual report came from 179 US-based firms including 48 in the AmLaw 100, 49 in the Second Hundred, and 82 “midsize” (US-based but outside the AmLaw 200).

In relation to Biglaw lawyers writing down the amounts of their invoices before they send them to clients, you wrote, “Put more simply, as an industry we seem irresolute about the value of the work we perform for clients.”

May I propose an alternate explanation? The increase in pre-billing writedowns comes after years of rate growth exceeding inflation – that is, with BigLaw becoming more expensive relative to the general economy. Perhaps the partners are writing down the bills not because they don’t believe in the general value of their services, but because they quietly acknowledge that they are charging more per hour than their services are worth. What would cause them to face that fact? Big firms didn’t have to compete on price when their large clients had only a few choices, all equally large firms, who also didn’t compete on price. As the top clients have opened up to hiring the mid-tier (fiercely price-competitive), and as alternative providers have entered the market, the BigLaw firms now face a wider competitive field

Interesting. The theory you propose, to have explanatory and not merely descriptive power, must at some level be premised on “What changed?” In other words: Since write-downs have always been with us, what would have precipitated their becoming more generous, pervasive, and sizable of late?

Your suggestion that our industry’s recent-ish history of raising rates comfortably in excess of inflation strikes me as filling that bill. Couple that with clients’ heightened sensitivity to/scrutiny of law firm bills ever since, well, ever since 2007-’08 if you subscribe to the conventional wisdom. and it makes sense.

Permit me a closing speculation: Will we see the emergency of a small tier of “Super Maroons” (if there are a couple of dozen Maroons, there would only be room for half a dozen “Super Maroons”) who will retain essentially unfettered pricing power?

For partners, rack rates in large law firms outside maybe the top 30 (or so?) firms are fairly aspirational in most cases. Basically, what could a brand new client coming to the partner for a sophisticated piece of work in the partner’s specialty be charged per hour in the abstract? It is also an anchor to be used in billing rate negotiations with existing clients.

Also, the market for transactional work is reasonably transparent. Anyone paying attention can find out what his or her competitors are charging through a variety of different channels nowadays. The partner is going to have a very good idea of a what a particular transaction is worth to the client and what is defensible. So does the client. And the partner also knows what the firm’s realization tolerance is for the particular type of work. Discounts at billing tend to reflect all of this knowledge if the partner cares about the long-term dynamics of the relationship (both with the client and the firm). And so the partner is going to send out a bill that will get paid. Far preferable to haggling after the bill goes out when you went over “budget” using full blast A rates. That needlessly annoys transactional clients and the firm alike.

Maybe litigation is the same?