John Adams notably wrote that “facts are stubborn things.” Words, however, can be fluid, flexible, and subject at times to arbitrary diktat. This last sense was famously expressed in Alice in Wonderland “When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.” “The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

Today I’d like to write about four words universally used in Law Land which, I believe, have been twisted so far beyond their intrinsic sense as to act as continuous distorting lenses on our perception of firms and their performance.

I realize I’m about to argue against conventional usages so widely employed that a handy retort could simply be, “It doesn’t matter what these words originally [or intrinsically] meant, all that matters is that everyone understands and agrees on what you mean when you invoke them.” But I maintain that sloppy language leads to, or reflects, sloppy thinking.. If nothing else, I feel compelled to point out what is, to an economist, obviously misguided or worse.

Demand:

The standard quantitative industry reports (Citi, Thomson Reuters PeerMonitor, others) use “demand” to connote aggregate law firm revenue. The fundamental oddity here is that revenue is, well, revenue, which is the measure of what clients are paying to supply their demand for legal services from law firms. The quantity of demand for law firm services can rise or fall without regard to or even in inverse correlation to revenue collected by firms.

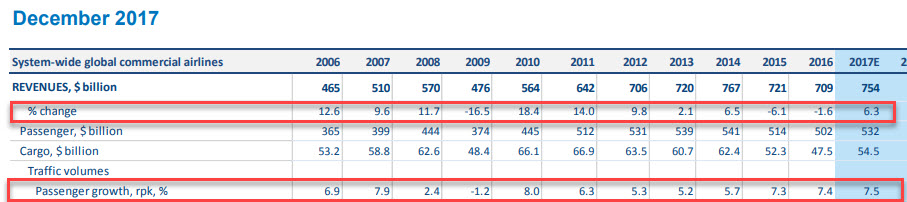

A simple example should clarify the difference: Every year the International Air Transport Association (IATA) publishes comprehensive statistics on the economic performance of the airline industry. Here’s a pertinent snippet from their most recent chart, where I’ve highlighted the % change in industry revenues and the % change in passenger growth, which they shorthand as “rpk” (revenue per passenger kilometer). You can see that in no year over the last 12 were these two numbers the same and in 2016, the last full year’s worth of data, revenue change was a negative number while passenger miles flown was a positive number.

Are our imaginations so impoverished that we can’t figure out a better measure of demand for our services than the sum total of how much we can get away with charging clients?

Equity:

We have long since become accustomed to the coinage of equity partners as distinguished from non-equity partners, but it’s not the oxymoronic quality of the second of those categories that I’m interested in today. (“Income partners” works somewhat better in terms of semantics, but isn’t perfect–a nit to pick another day, or never.) I’m interested in the implication that full-bore equity partners have an economic ownership interest in the firm. Let’s unpack what they actually do have and see how it squares with the conventional meaning of equity in finance and economics. What they do have:

- A vote on substantial and material changes to the firm itself–but, as reported in this month’s American Lawyer, this is an eroding franchise.

- An expectation (but not an entitlement) to some discretionary share of the earnings of the firm following year-end;

- And a requirement that they contribute to capital in an amount determined by a formula often constituting a function of their annual compensation. In almost all cases, this mandatory capital contribution does not earn interest, is subject to unilateral demands that it be supplemented at any time, and following separation from the firm is repayable in amounts and on a schedule determined solely by the firm. Even hedge funds offer periodic windows when investors can withdraw their money!

Does this resemble the concept of “equity” elsewhere in the economy?

Only in a remote sense. One of the most important characteristics of equity ownership, certainly in publicly listed companies and subject to shareholders’ agreements or other contractual provisions in private companies, is that the stake can be bought and sold. The market for equity in any given organization may be thick or thin, highly liquid or afflicted with price opacity and high costs of search and transaction fees in general, but there is a market on which one can exchange one’s equity interest for cash.

Not only is there no market for an equity partner’s share in a firm–which often can characterize many other closely held organizations coming in all sorts of legal forms–there is no provision for departing partners to sell their share to the firm (or to anyone else in the world for that matter) under an appraisal valuation, a right of first refusal, an auction process, or otherwise. This law firm partner’s “equity” has no present or future or terminal value.

You are free to defend our odd usage of the term, but all I ask is that you recognize Law Land distorts what rank and file businesspeople and economists would assume the word means.

Productivity:

Industry usage is that productivity means billable worked hours per lawyer. This turns inputs and outputs on its head. Hours worked is an input measure pure and simple, but productivity is defined (typical Econ 101 textbook) as “output per unit of input.” This is not far removed from Orwell’s “Ministry of Truth” in terms of turning what words mean upside down.

I know some readers will attempt the jujitsu move in their minds of arguing that billable hours “produce” revenue to the firm. Nice try. What any organization produces is the goods and/or services that clients come to it for and purchase. Clients, trust me on this, do not come to your firm to write checks and call it a day. To generate revenue, organizations must produce the goods and/or services they’re known for, but in no tenable sense does that mean the revenue is what the firm is producing.

Profitability:

According to innumerable MBA programs, Accounting and Econ 101 textbooks, common sense, and the entire universe of business journalists and Wall Street analysts, net profit is, as the redoubtable FT puts it:

The profit of a company after operating expenses and all other charges including taxes, interest and depreciation have been deducted from total revenue. Also called net earnings or net income.

But despite the universal assent to this straightforward definition everywhere else in the economy, that’s not the way we in Law Land use “profitability.” We (The American Lawyer and the rest of the legal media, managing partners and executive committee members, recruiters, etc.) have decided that what we mean by “profitability” is, yes, income minus expenses, but calculated before we pay the equity partners.

Imagine a publicly traded company deciding that, henceforth, it would report profits before paying middle and senior management. Even the non-securities lawyers in the crowd can imagine how long it would take before the SEC opened an inquiry on this.

On the other hand, reporting as we do has undeniable cosmetic advantages: We can as an industry boast of profit margins anywhere from 30–50+% of revenue, which, if calculated under GAAP, would indeed be enviable: So enviable, indeed, that they would attract a host of new entrants seeking to compete them away. But since that hasn’t happened, it may be that we have not pulled the wool over the world’s eyes. Maybe all we’ve done is annoy our clients, encourage even greater innumeracy and lazy thinking about the business our firms are in, and once again decided that words mean what we decree and not what the rest of the world employs them to mean.

Bruce –

Great post.

This should be Exhibit #1 when addressing why clients complain that outside counsel don’t understand the clients’ business. How can they even understand each other when the definitions of key terms are different for each party?

I’ve been annoyed by the “profitability” metric for more than a decade for a different reason, because it distorts the effect of leverage, and I’ve advocated measuring a firm’s financial success by its average lawyer income, rather than average partner income. Consider two firms, both grossing $2MM/year and with identical overhead of $800,000 each on all things except lawyer salaries. Firm X has 2 partners and 4 associates. Each associate is paid $100,000/year. Firm Y has 6 partners and no associates. Four of the partners In Firm X, the two partners make $400,000 each. In Firm Y, the six partners make an average of $200,000 each. In both firms the six lawyers together make $1,200,000 – maybe in Firm Y two partners each have 1/3 of the profits ($400,000 each) and four partners have 1/12 of the profits ($100,000 each). Firm X is more profitable to the partners, but it’s no more profitable as a law business.