It has become bromidic to observe that we’ve moved from a linear growth market, ever up and to the right, to one of flat demand (did someone say, “growth is dead?”). We are, in short, in a battle for market share.

Welcome to the rest of the economy.

That’s the bad news and the good news. It turns out the “rest of the economy” actually knows quite a bit about surviving and even thriving in a battle-for-market-share environment. Just think about it: How fast does demand for food, personal care products, retail banking, utilities, or transportation grow? Basically with growth in (a) GDP and (b) population. In the very low single-digits, in other words.

But just by virtue of my listing those sectors, you’ve already begun to realize, and imagine, how particular companies in those areas can work on out-growing their sector. Food? Be Whole Foods. Personal care? Be Gillette. Retail banking? Be Countrywide or Washington Mutual. (Actually this is one at the bullseye center of the economy where you better tread ever so gingerly.) But you get the idea.

That’s why a recent article in Strategy + Business is useful. (S+B is published by the former Booz & Co. consulting firm, which had to have been one of the most unfortunate names known to man until they were acquired by PwC and renamed “Strategy &,” which confirms that you should never jump to conclusions about the worst possible name.) The article is Growing When Your Industry Doesn’t, and here’s how it starts:

If we had a nickel for every executive who appeared on CNBC and blamed his or her company’s inability to grow on a weakness in the market, we’d be richer than Croesus. Of course, there’s a reason this explanation for uninspiring performance is so common: It’s readily available. At any given time, roughly half of all industries are growing below the level of GDP. And it’s only natural to blame something external for one’s problems.

The trouble is, a weak market isn’t a valid excuse. Plenty of companies that achieve above-average shareholder returns compete in average or below-average industries.

In other words, it’s up to you as leaders of your firm to figure out a way to achieve superior performance in industries “that aren’t doing anything special—that are just bumping along with the economy,” as they put it.

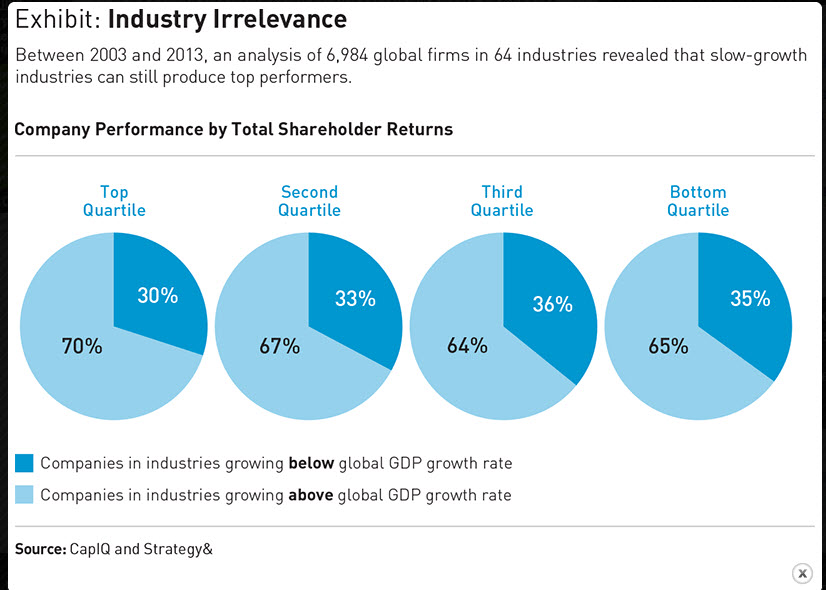

It turns out superior performance not only can but has been achieved regularly in every industry—so much so that the success of individual companies turns out to have essentially zero correlation with what industry they’re in: The authors call this “Industry Irrelevance,” and here’s how they illustrate it:

Looking at this it’s hard to discern all but the most imaginary pattern between hot and cold industries and hot and cold performance of individual firms. Essentially I summarize it thus:

- Companies in industries growing below the global GDP growth rate represent 33% of each of the four quartiles of total shareholder returns, plus or minus 3%. And

- Companies in industries growing above the global GDP growth rate represent 67% of each of the four quartiles of total shareholder returns, plus or minus 3%.

I dare you to tell the difference between these sectors if I removed the labels from the chart.

Excellent article but would not give up on the supply side so easily. This can be a huge competitive differentiator and I would argue if you put the same level of effort in attracting, growing and cultivating talent that you put into optimizing business processes you can have both.

Mike:

Interestingly, you’re the second person to suggest this (the first was on the phone to me so not recorded here for obvious reasons).

This may be a topic worthy of further exploration in a future column. In the meantime you may be aware of my other company, JD Match.

Bruce,

Great post as always.

There is huge potential for firms to excel on the demand side. We work with a number of firms, large and small, on process optimization and the elimination of waste (among other things). Certainly there’s no shortage of improvement opportunities in legal processes and in the business and administrative processes that support the lawyers.

The challenge is, as usual, getting a critical mass of the profession to sign on. Heads tend to bury themselves in the sand, fingers point to the office next door (“I’ve got a really efficient practice, but my partner down the hall could really use your services…”), and lawyers claim to be far too busy to waste any time thinking about improving.

Firms that make the commitment, that invest time and resources in improvement, and that provide support and incentives to overcome reluctance to change are starting to reap the benefits.

Let’s hope the others read your posts and begin to see the light!

Thanks,

Karen.