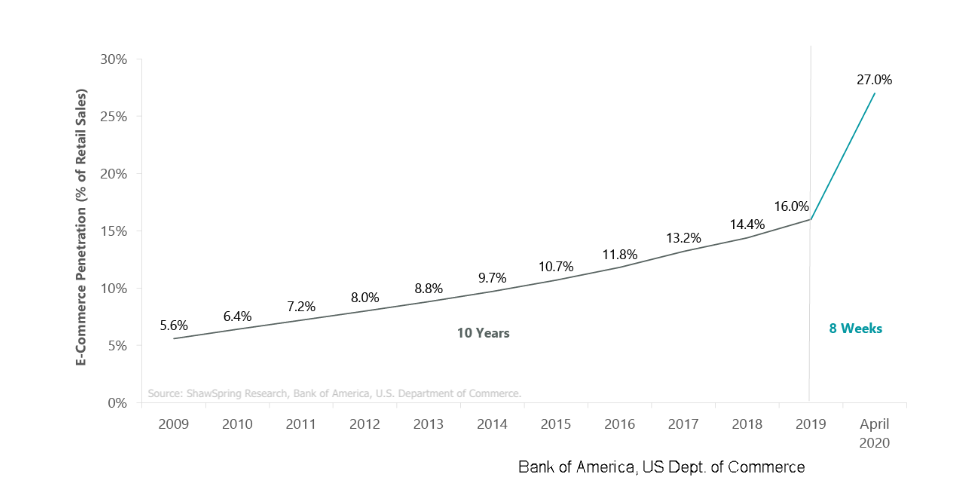

If one is looking for an image to encapsulate the Covid-19 “Slingshot” phenomenon, you will find an embarrassment of riches. But this has to be one of our favorites.

In 8 weeks–a heartbeat in a human lifetime–the penetration of online retail increased by 11 percentage points, or 69%. It took from 1994 and the first online e-commerce transaction to get from zero to the first 11 percentage point share in 2016–22 years, or nearly two and a half decades. (The ratio of 22 years to 8 weeks is 143:1.)

Other examples are all around us. According to McKinsey, in “The CEO moment: Leadership for a new era” (July 2020), Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center scheduled 2,000 telehealth visits in 2019; it’s now taking care of 5,000 a week (a ratio of 132:1). In Dubai, the conglomerate MAG shifted 1,000 suddenly idled ushers and ticket-takers at its movie theaters into clerks for its online grocery arm–in two days. Best Buy had been gingerly testing curbside pickup at a handful of pilot stores–before rolling it out to every store in its network in (yes) two days. It took Unilever twice as long (four days) to convert manufacturing lines making deodorant into making hand sanitizer.

These rapid-fire adaptations vindicate what an unidentified CFO told McKinsey last month about shifting resources: “What I thought would never be possible, I can now do in two weeks.”

CEO’s from a variety of industries are thinking hard about what changes Covid-19 opens up.

A classic strategy consulting question–because it’s truly a good question–has long been, “What would a complete outsider do?”

Now you have a once-in-a-lifetime chance to ask yourself “What’s your Covid-19 answer?” Both Lance Fritz of Union Pacific and Vivek Sankaran of Albertsons (I promised you a variety of industries) realized that zero-commuting/remote work and zero business travel have freed up wide blocks of time. They aspire to use it to focus more on what’s long-run important, not what’s short-term urgent. This may seem obvious. but it was every bit as obvious six months ago. Dare I ask what you did about it then? Don’t waste this chance too.

Nor are CEO’s coming to monolithic conclusions about things. Alan Jope, CEO of Unilever, and Natarajan Chandrasekaran, Chair of the Tata Group, have realized with a start what a “capacity trap” travel is. For both of them, this led to a “quite calming sense of control.” But Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, reports the opposite reaction:

[He] discovered early in the crisis that not having travel time took from [the firm] valuable reflection, focus, and restoration time. Fink reminds us that downtime at the water cooler with colleagues and travel by oneself can be creative openings and outlets for new thinking. Many CEOs have since adapted by booking “flight time” into their schedule so as to avoid spending all day, every day, on video conference meetings. In either case, the COVID-19 experience has made it clearer than ever that CEOs must be extremely intentional about how they use their time.

Critical is recognizing that whereas “leadership” six months ago was defined as and viewed through the lenses of strategy, business, culture, and people, now it’s as much more or more about morale, which means truly listening and connecting with people, and admitting your own vulnerabilities.

Show courage in the face of uncertainty, yes, yes, a hundred times yes. But also show that you’re human.

Perhaps the most notable feature of how CEOs are showing up differently is that they are showing more of their humanity. As Paul Tufano, CEO of AmeriHealth Caritas, explains, “This has been a sustained period of uncertainty and fear, but also a great opportunity to forge a stronger, more cohesive and motivated workforce. If CEOs can step into a ministerial role—extending hands virtually, truly listening, relating to and connecting with people where they are—there is enormous potential to inspire people and strengthen bonds and loyalties within the company.” Adds Alain Bejjani, CEO of MAF, “The people you are leading have big expectations of you. They want you to be perfect and often forget that you are human. But the more human you are with them, the more trust and empathy they lend to you. They understand you better. That gives you the ability to do so much more, as people give you the benefit of the doubt.”

Have the confidence to humanize things.

Deanna Mulligan, CEO of Guardian discussed how something as “simple” as an all-hands video or speech had changed. Out were rehearsals, professional staging and lighting. In was casual dress, and the (inevitable) greater intimacy of backdrops consisting of dens, finished basements and attics, libraries, dining rooms, and kitchens. Mulligan: “I’ve made some of my videos outside with the dog, something that we’d never have thought to do before. The feedback has been terrific. Our employee engagement scores, confirmed by regular pulse surveys, have been consistently on the rise since going remote.”

Respond to a larger organizational purpose than serving your clients and your lawyers and professionals.

Here’s Robert Smith, CEO of Vista Equity Partners, on what has changed for him (Vista is a private equity firm with 60 companies in its portfolio): Pre-Covid, we defaulted to thinking immediately about shareholder value above all else. “It was almost a muscle memory.” But soon enough partners, governments, suppliers, employees came into the picture–“stakeholder capitalism.”

Acknowledge–starting with yourself would be a good place–that you don’t have all the answers. Right now, you’d be kidding yourself to pretend, or behave as if, you’ve got this all under control. No one has this under control.

Absent control (a/k/a “decision making under uncertainty”):

- Hasten problem-solving by opening issues up to the collective intelligence of your firm.

- Build on the ideas of others, and then build on those.

- Iterate.

- Experiment widely with how things could be done differently.

In addition to the “Covid Slingshot” descriptor, one of my favorites is “unfrozen”–much of the organizational world has indeed been unfrozen from ways of doing things that were done that way because they were done that way because….

Now’s the moment to seize the collective adaptability and brilliance of everyone in your firm, from the senior-most partners to paralegals, librarians/knowledge management experts, etc. Have faith in their good will, creativity, and sheer ingenuity.

The Wall Street Journal reports that FedEx is experimenting with four 260-pound industrial robot arms deployed in their “World Hub” sorting facility in Memphis (nicknamed Sue, Randall, Colin, and Bobby) Although right now they’re only about half as fast as the best human sorters, they’re equipped with computer vision and AI developed by Plus One Robotics in San Antonio, and FedEx thinks they have promise. But they still need a lot of help:

The AI that powers these robot arms is learning all the time, but there are always situations that trip it up and require human intervention. No amount of AI, at least of the sort that exists now, can handle every possible “edge case,” those unexpected situations which are individually rare but quite common when considered all together. This galaxy of edge cases is a major barrier to fully autonomous AI systems.

You might think that if FedEx is experimenting with sorting robots, everyone is–and wouldn’t Amazon be in the lead there, since they sort so many more items than FedEx? Actually, while Amazon has intensively deployed robots to help move packages and sort sealed-and-addressed boxes, it still uses people to take goods off shelves or from bins and put them into other bins or onto conveyors. Why?

The company’s enormous and quickly changing inventory still defeats even the best combination of AI, computer vision and gripper, says Brad Porter, vice president at Amazon Robotics.

Amazon’s reliance on humans holds an immensely important lesson for you.

Consider that 25 years ago Amazon didn’t exist and today they employ closing in on 1-million people (OK, 876,000 per a spokeswoman.) Why not more robots? Ask Bruce Leak, founding partner at venture capital firm Playground Global: “The challenge is that humans are incredible. People are trainable, flexible, resilient and intelligent, and automation and robots aren’t any of those things.”

If that’s true of warehouse er, fulfillment center, workers, can you imagine for a moment that it’s not true of the professionals and staff at your firm? Try a little trust. Grant a little autonomy. Avert your eyes and when you take another look I bet you’ll see your humans have made amazing things happen.