The world is well into the greatest “natural experiment” in WFH ever seen. No one glided into this; it came as abruptly as an on-off switch. I’m sure the experience at Adam Smith, Esq. was fairly typical: One week (spanning the end of February and the start of March) we were giving a keynote at a Penn Law conference, proceeding down the Northeast Corridor for a retreat with a Washington, DC firm, returning to New York for lunch with a client, and then hitting the brick wall of self-imposed lockdown over the next 36 hours. (State and city-imposed lockdown followed shortly thereafter.)

Now, almost five months in, what have we learned?

Voices like McKinsey (“Reimagining the post-pandemic workforce”) and Harvard Business Review (the seven-part “Do we really need the office?”) have had the time, and in some cases the luxury of preliminary research, to begin discussing, “where to from here?”

As we all went through the looking glass from our sleek skyscrapers to bedrooms, dens, dining tables, kitchens, basements, and attics, universally everyone realized that (a) almost all of us were well prepared for it (the technology armamentarium to keep working; (b) people and businesses adapted with lightning speed, and (c) productivity barely suffered a hiccup and may be on a permanently higher plane.

If you believe research from MIT and NBER (I do), the share of employed Americans working from home went from about 5% to half, pretty much overnight. And while the experience of other countries, especially those in Asia, has substantially diverged from those in the West, what does it all mean for our future efficiency, capacity for collaboration and social cohesion, and, obviously, real estate spend.

James Gorman, CEO of Morgan Stanley, summed up succinctly where we are: “If you’d asked me beforehand whether I would have tried the experiment of sending the entire firm home overnight, I would have said, are you crazy? But now, we have shown we can operate with virtually no footprint.”

Now, if you ask me to predict what new equilibrium WFH vs. the office will settle down on after this is all over, I would echo Mr. Gorman’s first remark: Are you crazy?

And yet, we know a lot we didn’t know in January and February. For example, based on an extensive, and ongoing, survey of over 600 US-based white collar professionals, some developments I wager no one would have predicted back then are evident:

- Surprisingly, one of the issues many people struggle over most is not how to be productive but how to shut down. In the first few weeks of lockdown, half of employees reported working 10 hours a day or more, and even now the average day is 10% to 20% longer on average.

- Clear benefits to WFH have emerged, as reflected in these quotes: “more focus time,” “shorter meetings,” “more flexible time with family,” “learning what makes me most productive and how I can best manage my time and energy,” “it’s weird how normal everything has become,” “not missing the daily commute,” “getting into the groove of WFH,” “wanting it to continue,” and even “I love it” (several respondents).

- But it’s not a monolithic reaction. Perhaps unsurprisingly (although I for one hadn’t had occasion to consider this question before), one of the key differences between groups reflects personality traits. You might think that conscientiousness and introversion would correlate with success at WFH, but somewhat counterintuitively, the critical trait is a high level of “agreeableness,” which the authors describe as naturally maintaining healthy relationships, high quotients of empathy and sympathy, and being genuinely interested in how others are doing and the challenges they’re facing. In the “bad news for Law Land” category, file this: “Those who were highly neurotic — people who tended to exhibit higher levels of conscientiousness and self-awareness but who also, when under stress, tended to suffer anxiety, worry, and fear — had the most trouble adapting to all-virtual work.” You have been warned.

One of the key reasons WFH is successful now is very simple: We’re all in this together. Kid or dog in the background? No sweat.

Note how utterly unlike past programs of remote/flexible working this is: It’s all of us. The office crew is not the “real” firm and the WFH cohort is not the second class citizens, secretly viewed as a bit self-indulgent, with their motivation and commitment suspect.

So let’s stipulate the data show that people are productive, efficient, and accomplishing what’s in front of them. What happens when there’s not enough in front of them? When serendipitous connections and unplanned interactions occur, they tend to spark new ideas. The original 1950’s Bell Labs building in Murray Hill, NJ, was intentionally designed as two very long corridors radiating from a central hub containing the cafeteria, restrooms, mailroom, reception, conference rooms, etc. Why? So that people would be forced to run into each other more often. No floor, or wing, for “litigation,” another for “transactions,” etc.

The results? Merely the transistor, lasers, the UNIX computer operating language (the ancestor of and basis for Linux and Android), broadband microwave voice/data/video transmission, and much much more.

Steve Jobs may have had this in mind when he specifically directed that the Pixar Animation Studios in Emeryville be designed so as to maximize serendipitous encounters.

And three specific organizational functions, required for long-term health, competitiveness, and sustainability, are seriously undermined when physical encounters are out of bounds:

- Integrating new hires: This calls for both immersion in “how things are done around here,” and allowing them to bring their special strengths to bear on the organization’s problems. Apprenticeship requires master and apprentice being together, at least some of the time.

- Generating “weak ties,” which create bonds between those who don’t necessarily work closely with each but know that they subscribe to the organization’s vision: These ties strengthen innovation, product and service quality, and timely accomplishment of milestones.

- Fostering relationships: Under WFH, out go rotational assignments, cross-functional staffing, and other firm-wide experiences.

One more deep(er) data dive and then some preliminary thoughts before we close out this Part 1.

Microsoft has a cadre of data scientists, consultants, and engineers designed to help companies use behavioral data to identify and fix failures and miscues in communication, unforeseen logjams, “standard” processes that entail unnecessary friction, and employee demoralization in general.

When WFH hit Redmond, they went to work diagnosing their own firm. For better, if you’re a data junkie, or for worse, if you instead worry much more about privacy, the analysts could measure patterns across their 350-person “Modern Workplace Transformation Team” (I know, I know; but they are a software company). Their tool of choice was a homegrown application called “Workplace Analytics,” which tracks activity in Microsoft 365 (the newish name for the familiar office suite of Word, Excel, PowerPoint, Outlook, etc.) They could analyze aggregated and “de-identified” (their word) metadata from calendars, email, and IM’s and compare it to metadata from a pre-WFH period.

What did they find? Well, it’s nuanced, but:

- Whether collaboration increased or decreased seemed critically dependent on the job function. Salespeople dramatically increased their collaboration time with customers, but the manufacturing group went in the opposite direction, streamlining connections with suppliers.

- On the other hand, while time spent in meetings increased somewhat (+10%), the number of meetings of 30 minutes or less increased 22% and those of an hour or more dropped 11%.

- The brunt of supporting the new world falls, not surprisingly, on managers: their time in the Microsoft “Teams” meeting platform doubled (7 hours/week to 14), and they sent 115% more IMs (for a benchmark, staff and line employees sent 50% more).

- Most intriguing to me is that employees grabbed the steering wheel in terms of controlling the rhythm of their own workdays:

- Most team meetings shifted from the 8 am –11 am window towards the 3pm – 6 pm window.

- Pre-lockdown, IM traffic dropped 25% at lunchtime; during WFH, only 10%

- And a new “night shift” spontaneously arose: IMs sent between 6 pm and midnight rose 52%

- Employees left to their own devices to arrange their days also invented novel ways to deal with the “always on” mindset of remote working. My favorite was the product engineering team that launched “Recharge Fridays”—no meetings allowed on Friday.

So where does this leave us?

I’ll take a stab at an executive summary so far:

- Human beings are admirably, shockingly, nimble and adaptable when need be.

- Change that sticks tends to emanate from an alchemical combination of bottom-up experimentation and top-down blessing, encouragement, and example.

- The office is dead; no one will ever commute to a major city’s downtown again.

- The office is alive and well; when we emerge from under this surreal veil, we’ll pick up exactly where we left off.

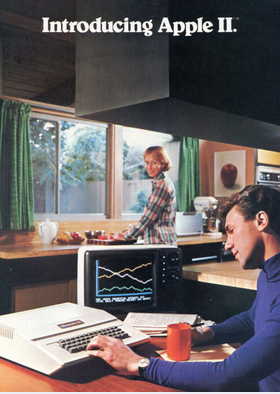

You can see from the final two that I don’t subscribe to the current Manichean vogue of those prognosticating on the future of the office. They’re not disappearing but they will be reappearing in dramatically changed form—smaller overall by far, more flexible/modular space, densely populated with a mesh of smart screens and computer hardware in all form factors.

To recap: I believe offices enhance and even just plain enable certain core organizational functions, but I also believe that as of January firms who had thought deeply (clean sheet of paper, amnesty from tradition and habit) about why do we have offices and what optimal design elements are required to support high-priority collaborative/connected/humans-together initiatives, were so few as to be essentially invisible to the mainstream.

Not for much longer.

Stay tuned for Part 2.