The following column is by Antonio Leal Holguin, Director of Latin America for Adam Smith, Esq.

I recently spent three days in Lima. A metropolis of close to 10 million people, Peru’s capital is one of Latin America’s most vibrant cities and a famous culinary destination. Aside from enjoying the warm hospitality of limeños, great food and giving the keynote at a conference organized by an exciting group of forward-looking lawyers, during my visit I got a sense of the state of the Peruvian legal market and what’s keeping firms up at night. A lot of people’s attention seems to be focusing on the fight for lateral lawyers in an increasingly competitive market and what the new slow-growth environment will mean for firms’ business.

The shape of the legal market

he forces of globalization and the country’s robust growth in the past 15 years or so have led several international players to set up shop in Lima, either through combinations with local firms or brand-new offices. According to our research, Peru is the fourth destination for international law firms in Latin America, after Brazil, Mexico and Colombia. (It is also the fourth recipient of Foreign Direct Investment in the region after Brazil, Colombia and Chile, according to Santander, a bank.) Growth of international firms in Peru is in line with regional trends. NLJ 500 data shows that Latin America outpaced Asia as the fastest growing emerging market for AmLaw 200 firms between 2014 and 2015. These firms more than doubled the number of lawyers in the region between 2010 and 2015 (ALM Intelligence.)

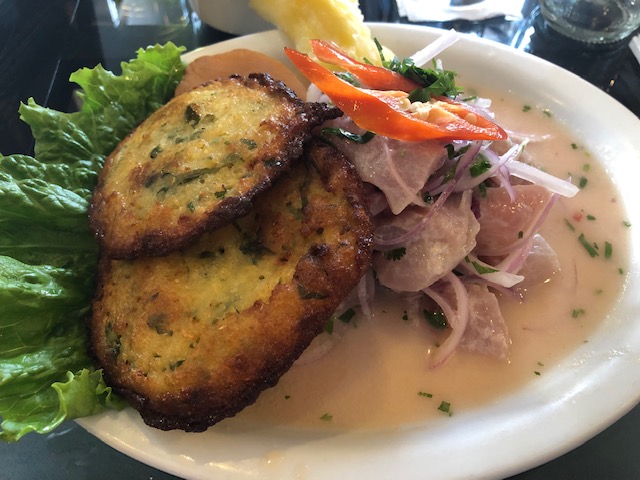

Then there are the new entrants. Some of the Big Four are dipping their spoons in the legal services ceviche. They’ve been building sophisticated teams and approaching the market in a purposeful, business-like manner, putting forward value propositions that leverage their accumulated knowledge and technological capabilities. Big Law alums and forward-looking lawyers have set up exciting New Law companies with distinctive offerings, which include everything from promises not to charge by the hour to incorporating behavioral design thinking in legal practice.

Like elsewhere in the legal universe, clients have become more discerning and demanding. Some of the most sophisticated corporations operating in Peru have become more deliberate in how and when they hire outside counsel. They have also strengthened their teams to handle more matters in-house and thus have become “competitors” to law firms. (An obvious, but frequently ignored point about the impact of globalization in our legal markets is that change in client-law firm relationships also comes through local corporate counsel adopting practices their legal department has implemented in more mature markets.)

The Peruvian legal industry has long been very competitive and not as concentrated as other Latin American legal markets, but the forces we’ve been discussing – globalization, new entrants, more discerning clients – have made it even more so.

While there are divergent opinions on the extent to which international firms have transformed the market, most people tend to agree that it has accelerated the process of firms running themselves in a more business-like manner and that it has increased competition for clients and talent. Local firms who joined global players have had to adopt standard business practices. By doing so, they’ve begun servicing clients in a more modern way, forcing local competitors to keep up to stay in the game.

Not surprisingly, quality of legal expertise is not a differentiating factor among firms that vie for top work. Therefore, fees have traditionally been very competitive (an analysis by Semana Económica, a business magazine, shows that Peru has some of the lowest rates in the big economies of the region.) With a mandate to capture market share and the financial backing of their firms, local outposts of global players have adopted aggressive pricing strategies. Coupled with new types of offerings in the market, the battle for clients and price pressures won’t abate any time soon.

Then there’s the battle for talent. While there’s little data on this, spin-offs and lateral hires seem to have become more common. There’s been significant movements of star lawyers or entire teams from one firm to another. Global players (and the Big Four) have been building up their teams. The local firms have had to expand their practices offerings to match those offered by the global firm. Lawyers must come from somewhere and they can’t wait to train them. Where do they look? To top practitioners at top firms, of course.

There may be other culprits for the uptick in lateral moves and spin-offs: fatigue with the traditional law firm model, which many think skews compensation and control (equity, governance, visibility) to favor senior partners or even family members, and compensation systems built during bonanza years that fail in the new slow-growth environment.

In our recent Letter from Bogota, we discussed how the arrival of international firms and the responses it triggers from local firms tend to transform economically dynamic local markets – dominated by Local Hero firms – into highly competitive, globally-integrated ones. Like in Bogota, it may well be the case that some of the anxiety and uncertainty around lateral hires among Peruvian firms is rooted in their having adopted both partnership structures and compensation systems that worked well during the commodity boom but have become more burdensome in the new slow-growth environment. With a decelerating economy, it may be harder to meet revenue targets and keep promises to the firm’s younger cohorts.

Of course, this doesn’t affect all firms equally. Some were further along the “institutionalization” path when global players arrived. But it does force everyone in the market – at least everyone who matters – to review how it’s doing things, including how it’s paying its lawyers. In other words, regardless of whether it’s a new or old trend and how pronounced it is, the reality is that firms are facing great competition for clients and talent and they better have a strategy to successfully compete in both markets in what is shaping up to be a slower-growth environment.

Blues for the Peruvian Miracle

According to the World Bank, from 2002 to 2013, Peru’s economy grew annually at an impressive average rate of 6.1%. This is much higher than its neighbors Colombia (4.56%) and Chile (4.55%), and far above the regional average of 3.4%. Poverty rates fell from 52.2% in 2005 to 26.1% in 2013, the equivalent of 6.4 million people escaping poverty (World Bank.) But people are not optimistic that the so-called “Peruvian Miracle” can keep going at the same pace. From 2014 to 2017, growth slowed to 3.0%. The Peruvian economy is heavily dependent on commodities exports, so the end of the commodities boom and falling global demand for copper and iron have reduced growth.

BBVA, a bank, projects that the economy will grow at a rate of 3.9% in 2019 and 3.7% in 2020. The World Bank projects that growth in the medium term will be around 4.0%. (These numbers may look good for more developed economies but are mediocre for emerging markets trying to lift their population’s living standards.) And these projections may be overly optimistic, considering the Peruvian economy’s vulnerability to external conditions. China and the United States are Peru’s main trading partners, so China’s slowdown and the trade war between the two can negatively impact its economy. Things will get even worse if the United States enters a recession, the US Dollar continues to strengthen, and international financial conditions tighten.

The country’s intractable political crisis doesn’t help sound policymaking. After a series of clashes with the legislature, President Vizcarra recently announced his intention to call for early congressional and presidential elections. The move seeks to send home a congress that has refused to pass the anti-graft reforms the country desperately needs. Making things murkier, several former Peruvian presidents have been enmeshed in the corruption scandals involving payments from Brazilian construction company Odebrecht. Alan García, a two-time president, took his life when the police arrived at his house to take him into custody as part of the Odebrecht investigation.

With the Peruvian Miracle apparently coming to an end and the country’s political crisis making policy measures more difficult to implement, there’s a fair level of anxiety in the legal market about the cloudier outlook. This anxiety may be warranted. The boom years created a more competitive market. With growth slowing down, more players will have to compete for less business.

In this environment, many firms’ greatest enemy will be confusion and lack of clarity about who they are and what their business is. When the going gets rough, some firms tend to get nervous and become prone to doubting their model and shooting themselves in the foot. Classic examples in our markets include boutiques that decide to become “full-service,” thus losing their distinctiveness, firms that have traditionally pursued higher-end work going for lower-end matters just to keep people busy, and firms that adopt suicidal pricing “so we don’t lose clients.”

While confusion and distraction will lead some firms to join the downward march toward market irrelevance, others will be smart enough to adjust their strategies to the new realities, find new ways of being relevant to their clients, and commit to superb client service. Firms will have to choose which group they want to join.