Last week I spent three full days in Bogota, meeting with firms and colleagues, giving a talk at the always-wonderful “Gun Club,” and generally trying to soak up as much market intelligence as I could.

Although I’ve been to Bogota several times–our Director for Latin America, Antonio Leal Holguin, is based there–it had been well over six months and even in that period of time the tenor of the prevalent form of conversation had migrated pronouncedly. In the foreground of most discussions new attention was given to lateral partner hiring and competition for (desirable) lateral partners. Naturally, some firms felt somewhat under siege while others felt they had won away key talent from competitors. Why this new focus of attention?

The remainder of this column is by me (Bruce) and Antonio.

First, I should say that many other topics also came up spontaneously: Growth (a perennial), compensation, succession planning, the pro’s and con’s of networks, foreign “best friends,” and outright acquisition by other firms with an international footprint, etc. These are almost never in perfect economic (or psychic) equilibrium, so I was not surprised by questions surrounding them: But it struck me that lateral partner movements were at least perceived to be a new source of anxiety and uncertainty.

Can one offer any intelligent generalizations on this topic?

We start from “we’ve seen this before.” Specifically, we’ve seen it in other markets traditionally populated by “Local Hero” law firms with deep roots in the community, the metropolitan area, or the region. These are highly respected firms that, in the vast majority of cases, have survived the transition from the first generation of founding leaders to the second generation of builder/managers, and perhaps beyond. They have demonstrated their worth in providing value-for-money, cost-effective and client-pleasing legal services. To all appearances, they are solidly positioned organizations with comfortable runways ahead of them.

And then. If the local market is economically dynamic and vibrant (Bogota surely is!), other firms “discover” it. This happened decades earlier in Sao Paulo, appears to be achieving lift-off in Santiago, and is a repeated pattern across North America in regions or metro areas as varied as western Canada, the US Pacific Northwest, Silicon Valley, Texas, San Diego, Phoenix, and the list goes on and on.

Can one offer useful generalizations about how this tends to work out?

Yes; and the Local Hero firms may not welcome what we’re about to report.

In our experience and as masterfully detailed by the always incisive Nicholas Bruch (of ALM Intelligence) last year in “Barbarians at the Gate: The Invasion of Regional Legal Markets and How Mid-Sized Firms Should Respond,” data from nearly the past two decades of NLJ 250 reports:

- Those 250 firms (the 250 largest US-headquartered law firms by lawyer headcount) “have nearly doubled their geographic coverage,” adding nearly 1,400 new offices.

- Of course, “this has created a group of law firms with vast scale and geographic reach,” but even more interesting for current purposes

- “Many regional legal markets have been transformed over the past decade. They have transitioned from localized markets, dominated by legacy firms, to highly competitive marketplaces, fully integrated into the global legal services market.”

At the most general level, this should surprise no reader of Adam Smith, Esq. What may come as news is how much of this growth and change in composition of the law firm landscape has come at the hands of a distinct minority of firms: A mere 11% of the 250 firms account for 50% of all the new NLJ 250 offices launched since 2001. (Bet you didn’t know that!)

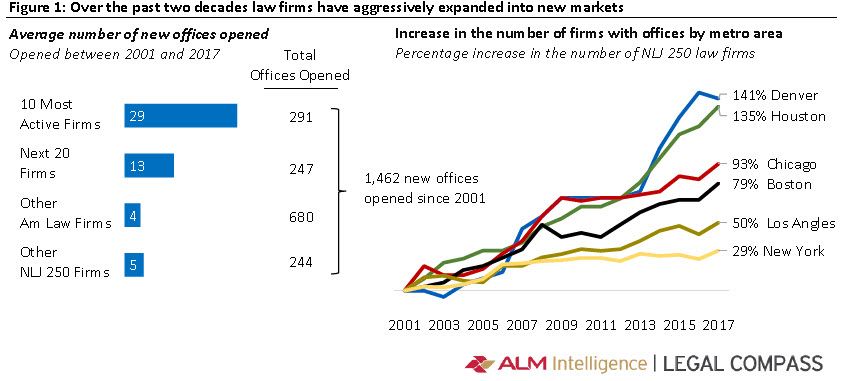

Here are a couple of nicely informative and highly legible charts summarizing some of the highlights:

You can see both how a tiny proportion of firms has accounted for the bulk of the new office openings and how some domestic-US markets seem to be more attractive than others.

[Sidebar for the US-curious: Why are Denver and Houston such magnets and New York evidently the least attractive? My surmise is that Houston and Denver were, compared to the rest of the country, relatively virgin law firm territory in 2001 or even, judging by the inflection points/slopes of the lines for those two markets, even immediately post-Great Meltdown in 2009. Supporting this: Most of the action is in the past 8 years, not the first 8. As for New York’s evident “repellent quotient?” The most competitive, saturated, expensive market of the six by far. Also, New York partners tend to be “stickier,” certainly at the high end of the market: Tougher to dislodge and more costly if you can do it. Finally, there’s the off-putting “40% Manhattan Tax”–the rough but ready rule of thumb that anything {rent, transit, housing, salaries, a ham sandwich} costs 40% more in New York than most places.]

But this is a “letter from Bogota,” so what might the experience of other markets augur for that market now that the world has well and truly discovered it?

The Colombian economy grew 4.6% in 2013 and 4.7% in 2014 (World Bank,) so international firms found it an increasingly attractive market. According to ALM Intelligence, Colombia’s big law market (using lawyer growth in largest firms as a proxy) grew 16% from 2013 to 2016. This is consistent with trends in Latin America for that period. NLJ 500 data shows the region was the fastest growing emerging market for AmLaw 200 firms between 2014 and 2015, outpacing Asia. The number of lawyers of AmLaw 200 firms in Latin America more than doubled between 2010 and 2015 (ALM Intelligence.)

Based on our own research, there are about 105 international firms with a Latin American practice (a dedicated team, with experience in the region. Not, “we’ve got a senior associate who speaks Spanish and some Portuguese.”) About 40 of those firms have offices in the region (mainly in Brazil and Mexico.) 14 have offices in Bogotá. To give you a sense of how dynamic this market is, this is less than Mexico (23,) but more than Peru (11,) Chile (10,) and Argentina (8.)

Part of the “anxiety and uncertainty” may be rooted in many firms’ having adopted a two-tier partnership during the good years of the oil bonanza (again, 4.6%-4.7% growth in 2013, 2014) and now finding themselves with a heavier payroll burden in an inhospitable economic landscape of: slower growth (1.7% in 2017 and 2.7% in 2018,) decreased foreign direct investment (down 14.1% in 2018, according to Banco de la República,) and increased competition.

This chart speaks for itself:

As a result of this, many firms may be struggling to meet revenue targets and, therefore, meet their promises to new non-equity partners or young equity partners.

This adds pressure to the talent cooker. How long does it take for dissatisfied younger partners to say “yes” to an attractive lateral offer or decide to open their own shop?And, if you try to match your competitors – paying generous sums to your associates and younger partners – what effect does that have on profitability? How will older partners react to lower numbers on their annual checks?

A final point: based on our research with Latin American clients, one of their concerns about international firms is that they may not have the right talent. International firms in Bogotá seem to be aware of that concern and have focused on hiring from competitors to build type-A teams to either strengthen specific practices or expand their services offering.

Our “key takeaways” from all this are classic good news/bad news:

- “New entrants destabilize local talent markets.” How could it be otherwise, really? New entrants have to find lawyers from somewhere, after all, and where do you suppose they are going to look other than at incumbent firms? Incumbents, in turn, who may have lost talent are not going to sit idly by: They will recruit on their own to restore capability and/or revenue, and the chain reaction has begun.

- “Local firms often lose from increased competition”–shrinking in headcount and market share. This may be unwelcome news, if you’re a Local Hero firm, but simple market logic would dictate that unless all the newcomers give up and flee with their unexpired office leases in tow, they will take some non-negligible market share. But here comes the good news:

- Local firms forced to up their game in the face of heightened competition sometimes “rethink and refine their strategy and enhance their day-to-day management practices.” Just as Detroit-based US carmakers eventually, and after great pain and sturm und drang, reacted to the Japanese invasion by improving the quality and market appeal of their offerings, so too local firms may find shelter in offering more distinctive, operationally efficient, services.

- And lastly, there are actually strategies to handle tougher competitors.

Which leads us to our final observation.

One of the classic modes of going wrong in a market analysis or projection is to fall prey to the “static fallacy:” To unconsciously assume that if X happens, there will be certain predictable direct ramifications of X, but terminate the analysis there. So, in this case, the “static fallacy” might look something like this: “If new and capable firms enter the market, local firms will (as an almost arithmetic truism) lose some partners, some revenue, and some market share.”

Contrast this to a more dynamic analytic view of how markets operate: Yes, let’s stipulate for purposes of discussion that some newcomers will successfully acquire some partners from some local firms: Now the question is, What happens next? In other words, what do those local firms do in turn? And how do the newcomers respond to that? And what are clients doing all along in this dance? You get the picture.

Local firms are not without resources, in other words. But the increased urgency of “rethinking and refining strategy” and “enhancing management practices” often benefits from a dispassionate outside perspective. The optimal goals and objectives may not form a straight-line extrapolation from the familiar.