Having spent last week in London, where every firm worthy of its PR news feed has at least mentioned “agile working,” it’s worth spending a few moments reflecting on what’s behind that shorthand.

The phrase clearly embraces the notion of being able to work (well, almost) anytime and from anywhere, but I think that properly understood it has to include a clean-sheet-of-paper rethink of a firm’s office design and how it uses space.

Given that occupancy is typically a firm’s second largest expense after compensation, I’m at a bit of a loss to explain why from my view there’s still more heat than light on this front (or talk than action). Now, that’s not entirely fair. For starters, judging firms by their City offices alone is to ignore the tremendous and growing investments in Belfast, Glasgow, Manchester, Perth, and so on. These address both the compensation and occupancy expenses with, as it were, a double-barreled approach.

Second, the staff:lawyer ratios today would be unrecognizable to a time traveler from, say, 1985. They might be tempted to protest, “how can we afford to pay lawyers to type?” Don’t scoff; an early and terminally benighted boss of mine uttered those unforgettable words to me in about that very year, when I offered to bring in my own very primitive DOS-based, green-screen IBM PC clone on which I’d taught myself WordPerfect. Last I heard he was an assistant adjunct professor at a community college.

But focusing on City premises seems fair to me since firms have invited the conversation by talking of “agile work.” My only additional observation on this score is that I see too little evidence of their following that admirable premise to what seems to me its logical conclusion, which is to challenge the underlying assumption of specific offices assigned to individuals. After all, vast swaths of the corporate world including accountancies, investment banks, consultancies, and the media have long since gone open-plan and “hoteling.”

But, since we have not departed the quaint precincts of Law Land, the inevitable caveats and elaboration:

- Space usage studies have fairly consistently shown that the typical lawyer’s individual dedicated office is actually used about two days per week; in other words its utilization is about 40%; the rest of the time the “occupant” is traveling, at clients’, in conference rooms, or of course working remotely.

- Some individuals—I categorize them as hoarders and/or dinosaurs—will hang on to their personal office space until you pry it from their cold dead hands. Let them. They will start out as a minority of a minority and their ranks will shrink from there. Leave peer pressure and the passage of time to work their own inexorable magic. In the meantime, do not manage for failure nor tailor important firmwide policies around outliers.

- What about confidential documents?, you ask. Indeed; what about them? I hope we can stipulate that your lawyers and professional staff exercise common sense and prudence in safeguarding clients’ and others’ privileged information. Sure, a cubicle is less private than a private office, but the healthcare industry seems to be dealing with HIPAA privacy regulations in massive call centers and other high-volume administrative production environments, and investment banks harbor confidences every bit as exotic or more so than the average lawyer. I would recommend you’d get a far greater return if you devoted the same energy to taking precautions against more significant data breaches and hackers.

- Lawyers are introverts; they don’t want to mingle or rub shoulders. Agreed. Get over it.

All that said, I mentioned we’d just returned from London, and so we have. One of the highlights of our meetings was being able to tour (thank you, Duncan Weston!) CMS’ new offices on Cannon Street, which are more cutting edge on this front than I, at least, have ever seen in a New York or City firm. Two large floors (down from seven at their previous address) of mostly open plan, unassigned workstations with dual-monitor computers, tablets, and mobile phones.

CMS also devotes generous space to flexible conference rooms in a multiplicity of configurations, a cafe and a proper restaurant and coffee areas and “lounges,” overall creating such an inspired and energizing reimagining of “the office” that the likes of high tech startups and PwC have visited to see what it’s all about.

A few years ago the City offices of a US firm we know well moved from a tiny floorplate building to a similarly generously sized one and took a less radical step, although that didn’t insulate the office managing partner from alarming lectures about the consequences of doing the unthinkable. What did they do? They simply mixed up practice groups, so that (say) a litigator might be next door to a project finance lawyer to an M&A practitioner to a funds lawyer. So what?

Well, actually so this: In relatively short order the office had incubated and launched a highly successful and brand-new practice cutting across traditional disciplines, but providing clear and convincing benefits to clients: “Boardroom risk.” Could it have happened without the random mixing up of people? Possible. Not likely.

This convenient and happy story points to what’s actually the most critical aspect of rethinking office space, and it has nothing to do with cost savings.

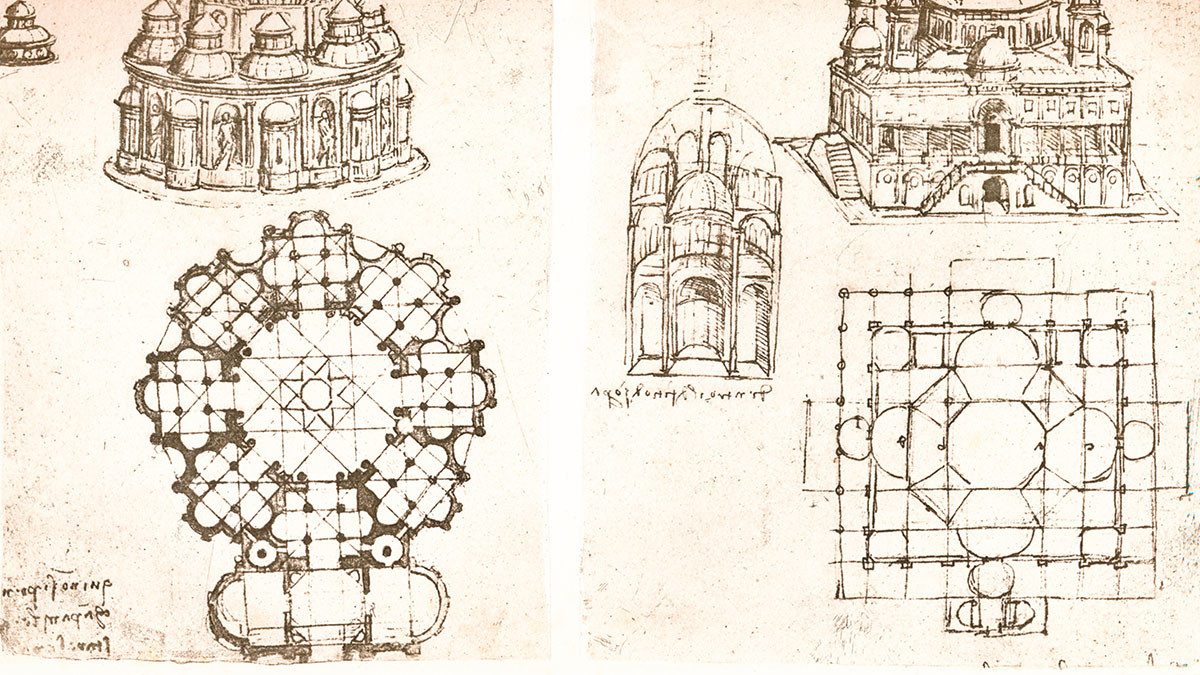

Serendipitously, the Harvard Business Review just published “The Innovative Coworking Spaces of 15th-Century Italy,” talking about the famous Florentine Renaissance workshops, or “bottega”’s. Here’s how they worked:

The Renaissance put knowledge at the heart of value creation, which took place in the workshops of these artisans, craftsmen, and artists. There they met and worked with painters, sculptors, and other artists; architects, mathematicians, engineers, anatomists, and other scientists; and rich merchants who were patrons. All of them gave form and life to Renaissance communities, generating aesthetic and expressive as well as social and economic values. The result was entrepreneurship that conceived revolutionary ways of working, of designing and delivering products and services, and even of seeing the world.

Florentine workshops were communities of creativity and innovation where dreams, passions, and projects could intertwine.

If this doesn’t sound terribly familiar, read it again:

- “knowledge at the heart of value creation”

- “aesthetic and expressive as well as social and economic values”

- “revolutionary ways of working [and] delivering services.”

The Renaissance bottega was modeled on a loose coupling of master and apprentice; tradecraft handed down intact and an invitation to look beyond the traditional; networking; and mentoring.

Here’s just one example:

Andrea del Verrocchio (1435–1488) was a sculptor, painter, and goldsmith, but his pupils weren’t limited to following his preferred pursuits. In his workshop, younger artists might pursue engineering, architecture, or various business or scientific ventures. Verrocchio’s workshop gave free rein to a new generation of entrepreneurial artists — eclectic characters such as Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), Sandro Botticelli (1445–1510), Pietro Perugino (c. 1450–1523), and Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449–1494).

Not bad for a day’s work, eh what Andrea?

Critically, these bottega were the furthest thing from abstracted academic think tanks or rich boys’ playgrounds: Their raison d’etre was to conceive new artistic and engineering forms and deliver them into the marketplace. (The long arm of patrons, after all, was omnipresent.)

There’s a wonderful and sadly archaic characterization of markets as “conversations.” Indeed they are. A product or a service offering is never ejected from a firm like a disembodied pod into the judgmental stream of commerce, never to be seen or heard from again. Just to state the premise reveals how disconnected from reality it is; yet many people I know, in their heart, think this is how markets work.

Instead, think of entering (or continuing to intersect with) a market as a true, vibrant, open-ended conversation. Imagine yourself at a cocktail or dinner party if it helps; you often have no idea where an opening gambit is going to lead. All I’m really suggesting here, as to how you design and organize your physical office space, is that you do so on the principle that it should do everything possible to facilitate and enable those conversations and not put unnatural hurdles and barriers in their way or put a lid on them before they get good.

Soon, all of us will be able to work any time from anywhere, so long as we can be in front of at least one screen; the Millennials may have gotten there first, but we’re all well on our way. Let’s just make sure that if the time we spend together is less than it is today, we make the most of it.

Thank you for this article Bruce. As a history graduate, I enjoyed it as much for the comparison with Renaissance Italy as for the investigation of agile working and office space in law firms.

My take is that the use of office space is but one aspect of truly agile working. Like you, I am struck by the prevalence of the phrase in UK law firm parlance. I have also been struck by how ‘agile working’ is used narrowly, to describe nothing more than an HR policy (flexible or remote working) or a facilities management approach (open plan / hot desking).

Agile working is so much more than this. I feel we’re missing the point and law firms are missing a great opportunity. Agile working is not about the firm – it’s about its clients. It:

– starts with client and market demands

– matches resources of all types to those demands

– focuses on outputs rather than inputs

– aims for maximum flexibility and minimum constraints.

In doing so, the firm may choose to implement open plan or flexible working, but both will be the means, rather than the end.

I recently posited a definition of agile working for the legal sector in an attempt to achieve greater clarity and a deeper purpose for agile working (see: http://www.katherinethomasconsulting.com/thoughts).

I suggest: “Agile working starts with the client and focuses on achieving outputs rather than managing inputs. It encompasses every area of the organisation and matches resources of all types to meet demands efficiently and adapt to changing market conditions nimbly. Crucially, agile working in legal services exists where business needs overlap with worker preferences and skills, resulting in increased productivity, efficiency, adaptability and innovation.”

What do you think?

Katherine

Katherine: Many thanks for contributing to the conversation. I’ve used a slide a few times lately that A&O developed to represent the legal marketplace ecosystem as they see it (law firms, LPO’s, the Big 4, Axiom and Integreon and NovusLaw &c.) and what strikes so many people who see it is not the variety of service providers available but the fact that A&O put the client at the center of this solar system and not the law firm! Hilarious that people react that way, but of course A&O is right to do so.

As are you.

Thanks again,

Bruce

How revolutionary indeed!! Thanks Bruce. Katherine