We haven’t talked yet about realization. Shall we?

The first time I saw this chart, it hit me between the eyes; your reaction may be similar. In a nutshell: Even if litigation “demand” is more or less steady, what about revenue to law firms from that demand?

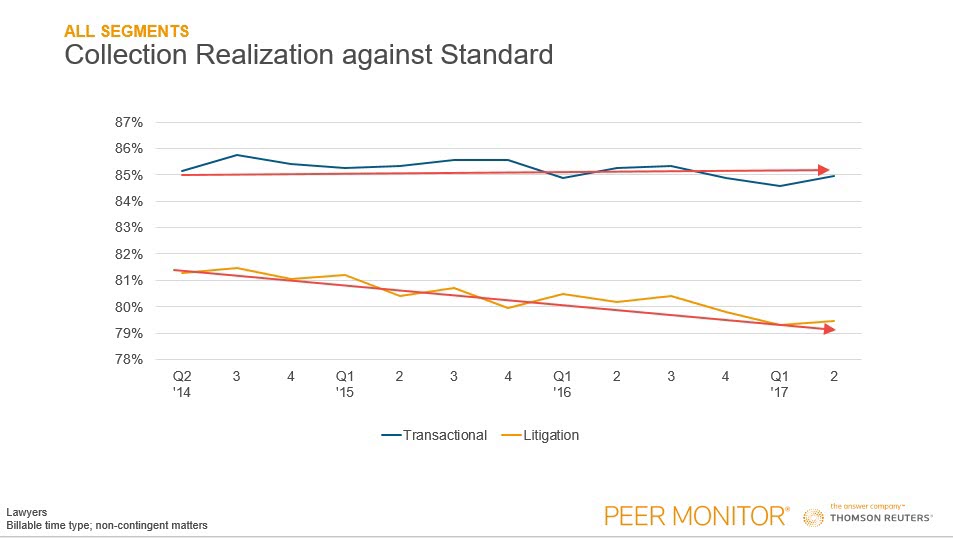

In somewhat more detail: This shows the last three years of realization against “standard” (rack) rates for litigation and transactional work from the Thomson Reuters Peer Monitor dataset of firms (I’ve added the red arrows to highlight the trends.) The story it tells is simple:

- Realization for transactional work is consistently, materially, higher than for litigation; and

- Transactional realization is holding steady, starting at 85% and ending at 85%, while litigation is in virtually straight linear decline over the period, starting at 81.5% and ending at about 79%.

- Stated differently, for every $1.00 of transactional work you billed in 2014 you collected 85 cents, and for every $1.00 of litigation you collected 81-½ cents. Today you still collect 85 cents for transactional, but barely 79 cents for litigation.

- The ratio is now 92% (inversely, 107%); if your average timekeeper bills 1,800 hours per year (and if rates across practice areas are equivalent), this means an 1,800 hour/year transactional lawyer brings in as much revenue as a 1,925 hour/year litigator. Stated a bit more symmetrically, you should treat a transactional lawyer billing 1,735 hours as productive as a litigator billing 1,865 hours,

Let’s step back for a moment from the litigation/transactional differences: This is not a pretty picture no matter how you slice it. If clients are consistently, across our industry, saying that they value our work at 80-85¢ on the dollar, one or both of two things are wrong:

- Clients think we’re charging too much (and theirs, after all, is the only opinion that counts); and/or

- Clients might be OK with the price if they got what they thought they bargained for, but they didn’t so they want some tangible recognition of their disappointment.

As Warren Buffett famously said, “Price is what you pay, but value is what you get.” There’s a sizable and growing mismatch here between Law Land and clients.

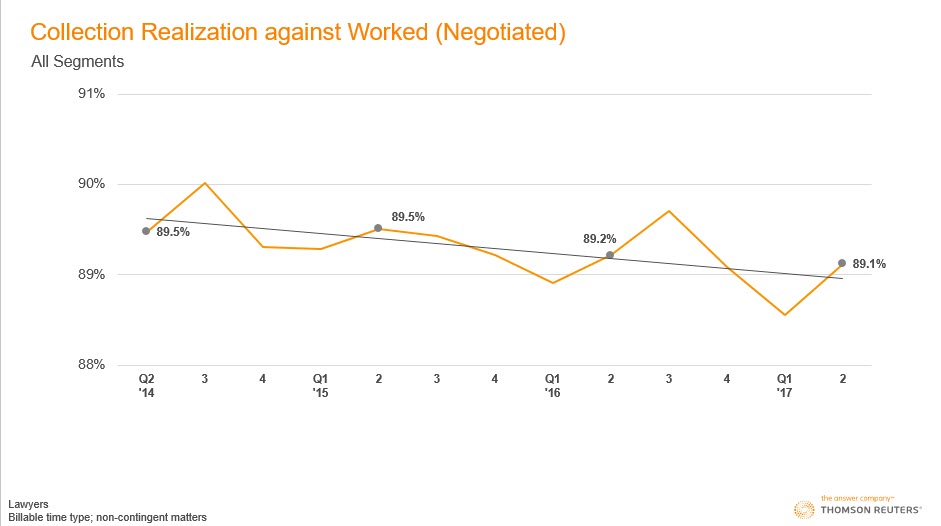

By the way, some more inquisitive observers have objected that measuring realization against “standard” rates is unrealistic because “nobody pays standard rates.” Ahem, that could be a problem right there, but moving right along the quants at Thomson Reuters have been good enough to compile a chart of realization against “worked (negotiated)” rates. In other words, realization against the agreed-to-in-advance discounted rate.

This chart is firmwide (all practice areas), but the inquisitors’ point is a firmwide point, so this serves nicely.

Not much solace here.

From an economic perspective, you could describe what’s going on in terms of price elasticity of demand: It’s evidently higher for litigation than for transactional services. That simply means that clients are less willing to demand “as much” litigation services as transactional services for the same price. The higher the clients’ price elasticity of demand, the worse for the providers of the service.

In a 2015 article, “A Refresher on Price Elasticity,” the Harvard Business Review had this to say about it (emphasis supplied):

This is one of the key metrics for marketing managers, says [Jill Avery, a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School]. “Our job is to create products and services that have unique and sustainable value for customers compared with other options available to them in the marketplace. Price elasticity is a way for us to measure how we’re doing in that regard,” she explains. “If my product is highly elastic, it is being perceived as a commodity by consumers.” It tells you how effective you are at marketing your products to consumers.

“A marketer’s goal is to move his or her products from relatively elastic to relatively inelastic,” she continues. “We do that by creating something that is differentiated and meaningful to customers.” When, through branding or other marketing initiatives, a company increases consumers’ desire for the product and their willingness to pay regardless of price, it’s improving the company’s standing compared with competitors. But it can go the other way. “It’s an important metric to watch because your product may become more elastic if a competitor starts offering compelling substitutes or consumers’ incomes go down, making them more sensitive to price,” says Avery.

It has been quite some time now since Law Land first began to see more and more “compelling substitutes” for BigLaw services, and while corporate profits are by some measures at an all-time high (as a proportion of revenue) and so it would be awkward to say our clients “incomes [have] gone down,” no one in touch with reality can deny that clients’ are exerting unprecedented pressure on legal spend.

But especially so, it appears, when it comes to litigation.

We might fittingly conclude this installment of our series with some notes about utilization, a/k/a “productivity.”

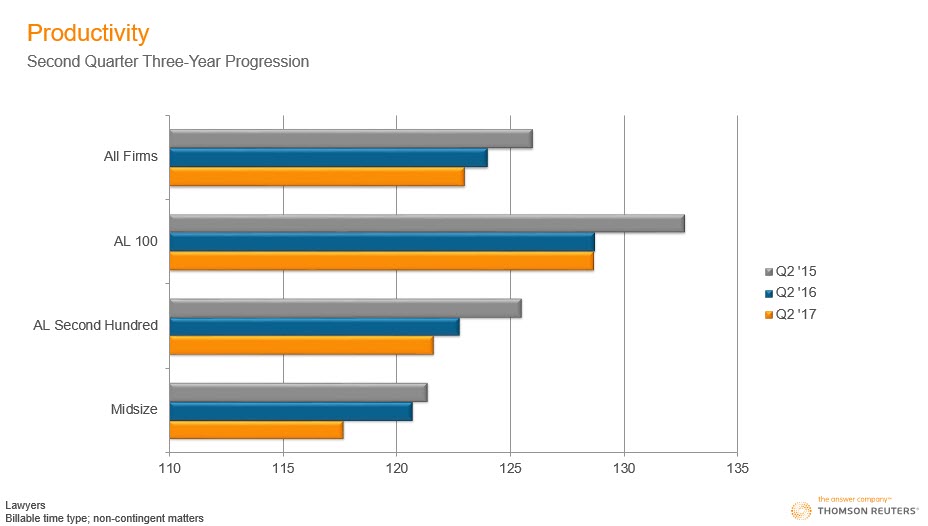

It has not looked healthy for firms in any segment over the past three years: Here’s the data on billable (non-contingent matter) time for the 2nd quarter of the most recent three years, in hours per lawyer per month:

Let me spare you the math: Extrapolating the Q2 results to a full year produces annual hours of 1,400 for the least busy cohort (“midsize”) and a hardly lofty 1,525+ for the hardest working (AL 100). Either would have meant the door for an associate, and raised eyebrows for a partner, as recently as, say, when today’s first-years were starting high school.

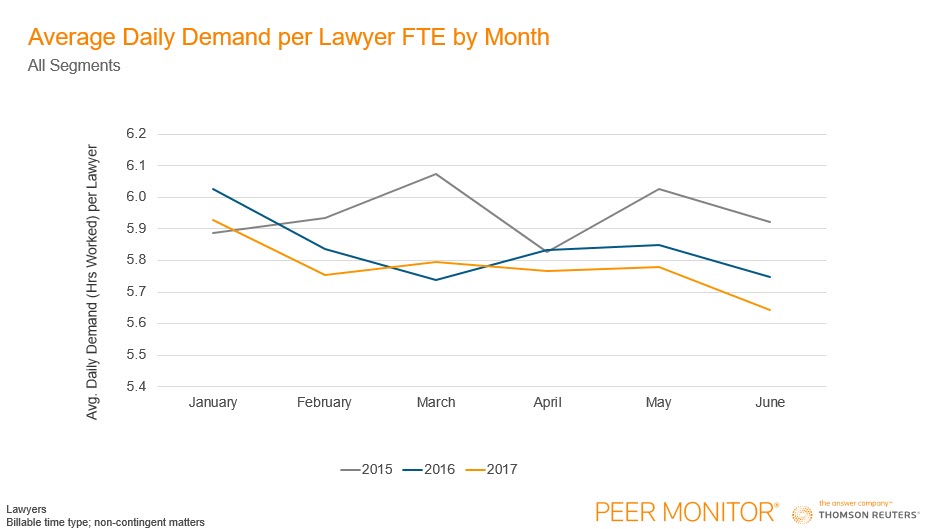

A final, ugly, portrayal of the data. Here we have average daily demand for the first six months of the past three years. The most telling observation about this is that at no time was the 2017 trend line the highest line on the chart.

These numbers on “productivity”/utilization are firmwide figures not broken down by practice area, so it would be fair of you to ask how is this germane to litigation exactly?

Believe me, if I had the data segmented into transactional and litigation, I’d show it to you but I don’t so I can’t. I’m unaware of any reliable industrywide sample dataset that can be filtered that way (but if you know of one, pipe up!). Bear with me while I float an hypothesis about what these figures mean.

We know that for nearly a decade, demand for transactional has actually been growing (not great, but >0), but litigation has been flat. We also know that total lawyer headcount in the firms in the Peer Monitor universe has been growing. Finally we just presented various windows into how people on average are less busy. My hypothesis is that it’s likely that more of the growing overcapacity is in the ranks of litigators than transactional types.

Finally, consider:

- Law firms can’t and don’t and never will engage in anything remotely resembling “just in time supply,” at least in the core firm itself (setting aside contract and third-party supplied lawyers, which aren’t reflected in the Peer Monitor data anyway).

- There is thus a lag, usually a looong lag, between secular changes in demand for a practice and the firms’ headcount devoted to that practice. There’s also denial and temporizing about whether the decline in demand is, in fact, secular. Some of this is rational.

- When an industry or a market sector is afflicted by excess capacity and enters the land of a battle for market share, there is a non-rational but almost irresistible temptation to shave prices to maintain share and keep people busy. Even if “busy” has to be continually defined down.

- We began this series by noting that across BigLaw, litigation has historically accounted for something on the order of 30-45% of revenue, and when the billable hour is your revenue model, that translates linearly into 30-45% of your lawyer headcount. That’s a large chunk of the firm to “right-size” quickly.

- QED: We have a lot of less-than-100% busy litigators.

In our next installment we’ll discuss how (a) the ever-increasing power of e-discovery tools, especially as applied to early case assessment, and (b) the predictive power of AI, will affect litigation as a law firm practice area.